Jagraon, a small township about 50 kilometres from Ludhiana Railway Terminus, has nothing much to distinguish it from other such towns on National Highway 5, except for an infamous, but very important bridge named after it. Till July 14 2016, when it was barred for traffic by the Railways, the original British-built Jagraon bridge, along with a parallel single lane bridge built in 1970 to accommodate the increasing traffic, was the lifeline for commuters in Ludhiana, Punjab’s largest city and industrial hub, which once led to the city being bestowed with the title, Manchester of the East.

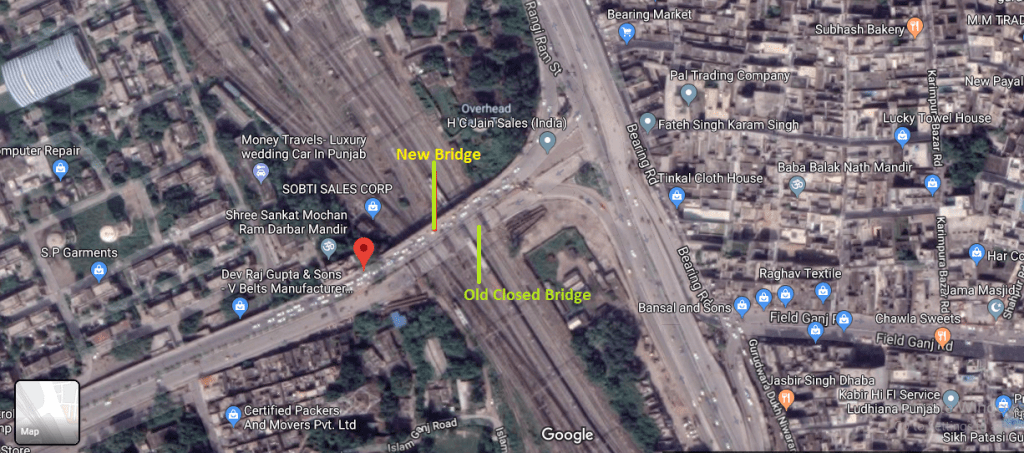

Built as simple Railway Over Bridges (ROB), the two Jagraon Bridges are located right next to the railway terminus and straddle rail lines that converge from Delhi and other places at the Ludhiana Terminus.

Ludhiana is broadly divided into two areas by the railway lines emanating from the terminus: a south-east line heading towards Sahnewal and Khanna, ultimately terminating at Delhi. The second is a northward line that takes you to Amritsar. If you are travelling to Delhi, the old city lies to the left of the line and the new city, with its modern residential areas and swanky shopping malls, on the right. The offices of Ludhiana Municipal Corporation, one of the main players responsible for the Jagraon Bridge fiasco, lies in Old Ludhiana along with offices of various departments.

The 1970-built bridge is critical now because it is the only one that connects old Ludhiana, where a majority of the factories and work places are located, with new Ludhiana – where most of the workers reside. “People from new city have only this one bridge now to cross over to old Ludhiana to attend their factories, offices and businesses in the morning. The same crowd heads back home in the evening using the same bridge,” said Rahul Medhra, an activist who has been at the forefront of citizen efforts to usher some semblance of order in this ‘city of chaos’.

As a result, during peak hours, the bridge has anywhere from 70,000 to 1 lakh plus commuters including pedestrians, resulting in traffic jams lasting over an hour, reducing the maximum possible speed of a vehicle on the bridge to 5–10 km/hr.

Bridge with a history

The old Jagraon Bridge has quite a history. In October 1870, the then Sind, Punjab and Delhi Railway completed the Amritsar-Ludhiana-Ambala-Saharanpur-Ghaziabad-Delhi line providing connectivity between Multan (now in Pakistan) and Delhi. The Jagraon Bridge was constructed in 1883 to further facilitate traffic on this route. “Our elders told us that a plaque on the bridge had fixed the structure’s lifespan at 75 years,” said Jaskirat Singh, an activist.

Singh says that the bridge was inspected in 1960 at the end of its official lifespan, and was found to be fit for further use. Looking at the growing number of vehicles, in 1970, the MC constructed a new single lane bridge parallel to the old one, making it a two way route.

The old bridge was inspected for safety again after 20 years in 1990, when the Railways decided to raise its height by 2.5 feet, necessitated by the introduction of electric trains on the route.

“While raising the bridge’s height, the railways barricaded the footpaths on either side,” says Rahul Medhra, who has been beating hard on the doors of the authorities concerned to bring about a change in the city’s traffic management policy. “The original bridge would have been good for another 100 years but the laying of an optical fibre cable weakened the foundation. Further, barricading of the footpaths led to people urinating on the foundation pillars of the bridge. This caused massive corrosion of the iron structure, ultimately making it unstable for any kind of traffic”.

The railways continued to use the old British-made bridge till 2010, when questions started being raised about its instability. Railway officials inspected the bridge, found it unstable, but for some reason did not take any action for the next six years. On July 14 2016, in a typical knee jerk reaction, railway authorities suddenly put a notice on the bridge saying it was closed for all commuters. All attempts to elicit information regarding this decision drew a complete blank from senior railway officials.

The closure has led to total traffic chaos, as the 70,000 plus commuters now have only the parallel bridge for commuting between the old and new parts of the city. The bridge has become the scene of major traffic jams, often extending for over two hours. An alternative road provided by the municipal corporation is even worse, as bottlenecks on it often lead to motionless vehicles lined up for over 3 kilometres.

According to data from District Transport Authority (now renamed RTO), the city adds 10,000 new vehicles every 15 days and has 24,08,107 vehicles for a population of 20,06, 504 (as per population growth projections with 2011 census as the base). So much so, on account of the rapid growth in vehicle numbers, the state government was forced to introduce a second number series, PB 91 (in addition to the census’ PB 10) for the city, thus making it the only city in Punjab with two series of vehicle numbers.

The buck never stops

Meanwhile, as the citizens suffer, the municipal corporation (MC) and railway authorities play the blame game. The MC has blamed the Railways for unusually long delays in commencing work on building a new bridge. “It took them eight months, after they closed the bridge, to present a cost estimate for the new bridge,” says Ludhiana Mayor Balkar Singh Sandhu.

In a letter written to the GM Railways, Sandhu said the MC deposited the total project cost of Rs 24.30 crore with the Railways on August 15, 2017 just over a year after the old bridge was closed. “The construction work was supposed to be finished within 10 months after the Railways finalised the contractor on February 10, 2018, but the work is nowhere near completion.”

The railway authorities, on their part, accuse the city’s politicians of deliberately adopting a go slow approach. “The bridge had a number of encroachments under and around it,” said R C Garg, Deputy Chief Engineer, Railways. “The MC did not move them before the elections due to fear of losing votes”.

Garg dismissed as rumours allegations of faulty design of the newly assembled bridge structure. “Yes, we found a small flaw while testing similar bridges constructed in other states like Kerala, and we are in the process of correcting that,” said Garg. Senior railway officials, however, refused to give any deadline for completion of the bridge. “We have missed so many of them in the past that it is pointless to set a date at this stage,” said an official on condition of anonymity. But we can assure you that the work is being given top priority and we can commission it in the next three months.”

Projects in limbo

Even though the MC has removed encroachments now, the civic body is yet to float tenders for construction of the slipway and up ramp for the bridge, which could take over three months. “While it is an important matter for the city, it really doesn’t come under my purview as the bridge doesn’t fall in my constituency,” said Surinder Dawar, a Ludhiana MLA.

Another MLA, Rakesh Pandey, too washed his hands off the matter saying that it was not his constituency. “I stand with the citizens of Ludhiana to seek a solution for the matter. But my role is limited to bringing it to the attention of the state government,” said Pandey.

The traffic congestion is not limited only to the Jagraon bridge. “It is a living hell,” said a commuter Manu Malhotra. “We do not have a single roundabout in the city where traffic jams are not a problem”. Citizens like Manu point to the politician-bureaucrat-business nexus as the root cause. A prime example is the proposed project to construct three bridges, which were to be built by a private firm, but has been pending since 2009.

The company in question, Soma-Isolux, was given a contract by the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) in 2009 for six-laning of the road on NH 1 from Jalandhar to Panipat. The estimated cost of the 272-kilometers road project in 2009 was Rs 2747 crores, which has now gone up to over Rs 6000 crores. It was to be completed by 2011, but remains incomplete even in 2019!

As a part of the contract, the company was to construct bridges/flyovers in Basti Jodhewal, Oswal Cancer Hospital, and Sherpur Chowk, three notorious traffic choke points in the city. However, 10 years down the road, the company is still far from giving any indication of completing the flyovers. But acitivists allege that it has been quick to fill its coffers by charging a toll tax at Basti Jodhewal Toll Barrier. The amount: Rs 125 one way and Rs 185 for 24 hours. As per estimates, over 1.5 lakh vehicles are expected to use these flyovers daily.

An astute politician, present Ludhiana MP Ravneet Bittu of the Congress who won the seat for the second time in 2019, organized a one-day dharna to stop collection of this toll. He alleged that the company had so far collected Rs 1800 crore from toll fees, without doing any work. Bittu held a meeting with senior company officials the same day and it was announced that the company will not charge the toll till the completion of work on all three Ludhiana bridges/flyovers.

Further, a deadline was fixed according to which the Jodhewal flyover was to be completed by June 30, 2019, and Sherpur Chowk and Oswal Cancer Hospital flyovers by January 2020.

But Bittu’s victory smile was short lived. Barely 31 hours after the meeting, the toll tax was back in place and other deadlines have been forgotten as no work is being done.

Traffic jams at a major choke point in Ludhiana. Pic: Welfare Society Senior Citizens’ Forum (Facebook)

Cheema Chowk, another congestion point in the city, was supposed to get a flyover under the elevated road project launched by the Akali regime to be built by the NHAI. The elevated road was to connect Samrala Chowk, in Ludhiana to Ferozepur Road Octroi Post, a distance of 12.7 kilometres, but later it was learnt that the project was only to be implemented on the Ferozepur Road, leaving Ludhiana residents in the lurch. Experts like Rahul Varma say the project is not really needed, but is being implemented all the same for some strange reason.

That is the Ludhiana commuters’ curse—badly needed road projects are never completed while road projects not needed get going.