The names of the three fugitive chimpanzees hunted down, shot, and left to bleed out on the baking Great Plains by a well-armed posse were Tyler, Jimmy Joe, and Reuben. Reuben’s loss hit the hardest; he was the original celebrity chimp of Royal, Nebraska (pop. 63). The lone survivor, Ripley, enjoyed his freedom on a local neighbor’s tire swing in a scene simultaneously Rockwellian and Orwellian; he was returned safely to his cage at the zoo. Fourteen years later, the man behind it all, Dick Haskin, lives with the painful memories of the primate massacre.

The story of that awful and ridiculous September day in 2005 is vividly told in Zoo Nebraska: The Dismantling of an American Dream. Nebraska native Carson Vaughan, 31, who now lives in Omaha, was in high school at the time of the insanity. He picked up the story in college and spent a decade interviewing more than 100 people tied to the horrific events, trying to figure out what the hell went wrong in the heartland.

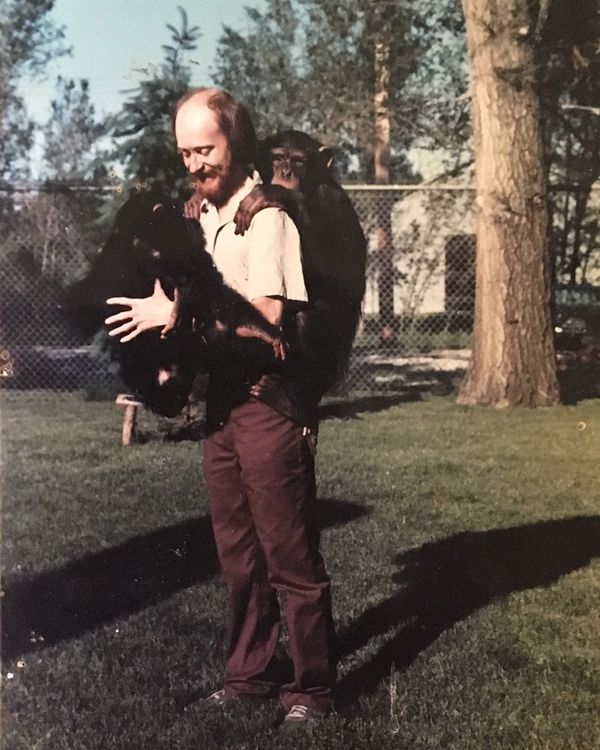

It all started back when Dick Haskin, the only member of his seventh-and-eighth-grade class, watched the documentary Miss [Jane] Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees. He would become mentor, caretaker, teacher, and best pal to Reuben, establish the zoo out of a single trailer, and then abandon it all, exhausted and overworked, leaving dangerous creatures to even less-credentialed successors. Zoo Nebraska’s demise as a functioning home for tigers, wolves, macaques, a bear, a lion, and others, is described in a passage that could introduce a dystopian George Saunders story.

On June 28, 2010, everything must go: the cages, the signs, the old Church-of-Christ-turned-visitor-center, the dust-caked aquariums, the maintenance equipment, even the wooden fence posts and the seven acres they enclose. Five years ago, the USDA revoked Zoo Nebraska’s license. The buses stopped coming. The parking lot emptied. Prairie grass reclaimed the walking paths, and the director begrudgingly relocated the animals that remained.

To top off the absurdity, the whole misbegotten adventure was funded by Nebraska’s most famous son, Johnny Carson. Vaughan spoke to Intelligencer about the tragic saga of Dick Haskin, Tyler, Jimmy Joe, and Royal’s main dude, Reuben.

Do you remember when the Zoo Nebraska tragedy went down? Is this a story all Nebraskans know?

It’s a strange thing, but I don’t. It was in our flagship papers like the Omaha World-Herald and the Lincoln Journal-Star and it made national news for like two days, but only as a small AP wire story in the back of the New York Times. People from the northeast part of the state certainly know about it, but even in central Nebraska, where I’m from, it wasn’t a major story.

Was it a decent zoo in its heyday?

Fair to say, over its 20-year run, it was never a first-class facility, but there was a point, during Royal’s centennial celebration in 1990, that the zoo was showing signs of success. It was only a couple of years old and had come a long way since it was just a trailer home by the highway. They had a few more buildings and the Carson Center for Chimps [a windowless concrete garage housing the apes] was about to debut. It was maybe on its way to becoming a self-sustaining tourist attraction.

It was obviously a source of pride in Royal, but was it a place people went back to again and again?

There’s not a lot of things to see in northeast Nebraska to begin with, and there’s not a huge population. In the zoo’s best days, people were definitely repeat visitors, young families going every weekend to see Reuben. The community loved Reuben as one of their own.

The two words I would use to describe Dick Haskin are decent and distracted. Accurate?

Yes. I would throw in optimistic, naïve, amateuristic, and afraid. He had a fear of letting people down.

While he wasn’t a primatologist, he knew apes to some degree, no? Scientifically and academically, he was an amateur. He had a bachelor’s degree, but never proceeded beyond that. He was trying to do his own studies with Reuben out of a trailer home in the beginning, but he didn’t have the proper controls or the proper environment.

Haskin was promised a job working in Africa with Dian Fossey. That ended with her murder. Why didn’t he just go to grad school to become a primatologist?

Today, he would be the first to tell you that after she was killed, he should have slowed down. But Dick went into a weird tailspin where he wasn’t being rational at all. He was scared and felt most comfortable returning to what he knew best, which was Royal.

Usually when you read tragic, weird American stories, like say the horrific Kansas water park death, there’s a megalomaniac “my way or the highway” type at the center of it. But Dick was different.

Dick was and still is morally opposed to zoos. His problem was that he didn’t know how to say no to other people. He also had tunnel vision. Once he brought Reuben to Royal, which is a small town even by small-town standards, everyone accepted his obsessive tendencies and just let him do his thing. Nobody second-guessed him or even checked in on him, really.

Too easy, but a man who hates zoos getting trapped in one of his own making …

It’s such an obvious sort of metaphor, but that’s exactly how it played out. He was the only person even remotely qualified to take care of exotic animals. He worked 20 hours a day because he had no choice. Zoos close [at night, but] the feeding and cleaning never stops. Dick’s daily sustenance became a can of soup, Benadryl, and countless bottles of Diet Dr. Pepper. All of these factors led to a lot unhealthy decisions — physically, mentally, and spiritually — that affected Dick, and ultimately a lot of other people.

Did he ever have second thoughts about acquiring Reuben?

Acquiring him, no. Bringing him back to Royal from his previous job at the Folsom Children’s Zoo in Lincoln, yes. He never regretted their relationship, but he certainly regretted starting Reuben on the path that led to his death. He often referred to Reuben as his son.

In the last chapters of your book, Dick is a broken man. Do you think he sees himself as a martyr?

It’s strange, but I don’t think he feels sorry for himself at all. He understands he made some cosmically bad choices, a million mistakes. I think sometimes he wishes somebody, anybody, would have sat him down and talked him through the very idea of the zoo in the first place, but he knows it’s on his shoulders.

Haskin didn’t agree to sit down with you until very late in your process. Did Zoo Nebraska change a lot after that?

I was fairly proud of myself that when Dick finally opened up, everything he told me was in line with the bones of the reporting I’d already done. That being said, a lot of the book is written from Dick’s perspective. Over the years, Dick’s friends kept telling him to see a therapist or a psychiatrist. By the time he invited me out to his homestead for an interview, he was ready to uncork it. It was very therapeutic for him. There was a lot of crying and pounding fists on the the table, 30 years of pent-up emotion.

You paint an unforgettable picture of Ripley swinging on a tire swing and eating strawberries shortly before his primate playmates are shot and killed. Where did that come from?

I found that particular scene years ago in a witness testimony filled out for the state patrol. I still vividly remember seeing that image — chimp on a tire swing — and it sustained me a long time. I kept my head down knowing someday the story would lead me there. But I had to piece together dozens of interviews with people who were there or at least knew something about that day. I combined those with a 40-minute-long dash-cam video I got through a public records request. There were also bullet discharge reports — all these different sources I put into a mega-timeline I pieced together to make cohesive sense.

I couldn’t quite tell: Did some members of the posse get a thrill out of shooting the chimpanzees?

I don’t think so. I didn’t talk to anybody who was part of the shooting who was gleeful about it. I assume you’re referring to the high-fiving after the chimps were dead. I honestly think it was a bunch of guys in a tense situation blowing off steam. I don’t think any of them thought, “Hell yeah, let’s go!” It was not a fun day.

You have to understand, Royal is a tiny place, and just about everyone was related to someone who was caught up in the zoo escape, either barricaded inside, or in the surrounding area, including young children. I think the militia realized chimpanzees are very dangerous and once the tranquilizers weren’t working, what do you do? I’m certainly not advocating shooting exotic animals, but they were cornered into making a horrible decision. Don’t forget, the community adored Reuben.

The only person I thought came out of Zoo Nebraska blameless was the woman who worked at the zoo for less than a year and tried to warn people of its flaws. Even Johnny Carson deserves a hit for blindly bankrolling the thing.

So many decisions were made based off an idea, not on reality. Johnny Carson never stepped foot inside the zoo, or even sent anybody to make sure it was a professional operation. He said rural children should have the same advantages as kids in bigger cities. Sure, but if you’re going to donate to a cause, especially one with live exotic animals, you should probably know something about it. Royal is not a community with the infrastructure for a proper accredited zoo. No actual primatologists were involved. You shouldn’t have exotic animals being handled by volunteers. I will say, though, I sincerely believe the story of Zoo Nebraska doesn’t have any heroes or villains, just a lot of flawed human beings doing what they think is best.

I’m surprised it didn’t turn Royal into a national punch line.

The shootings took place in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, right after the Superdome was evacuated, so the nation’s attention was on New Orleans. Otherwise, I’m sure Royal would have made Tonight Show monologues, which would have been fitting.

Were you changed at all in the writing of Zoo Nebraska?

I’m not a huge animal guy to begin with, so my fascination with Royal was always more about how this small community was dealing with the fallout from the zoo. But after ten years, I have come away thinking zoos of any kind aren’t great. Not long ago, I went to Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo, which has been ranked No. 1 in the world, but it’s hard for me to look at an animal stuck inside a cage and see anything but an animal stuck inside a cage.

Crossing my fingers here, how’s Ripley doing?

He’s alive and well in Florida.