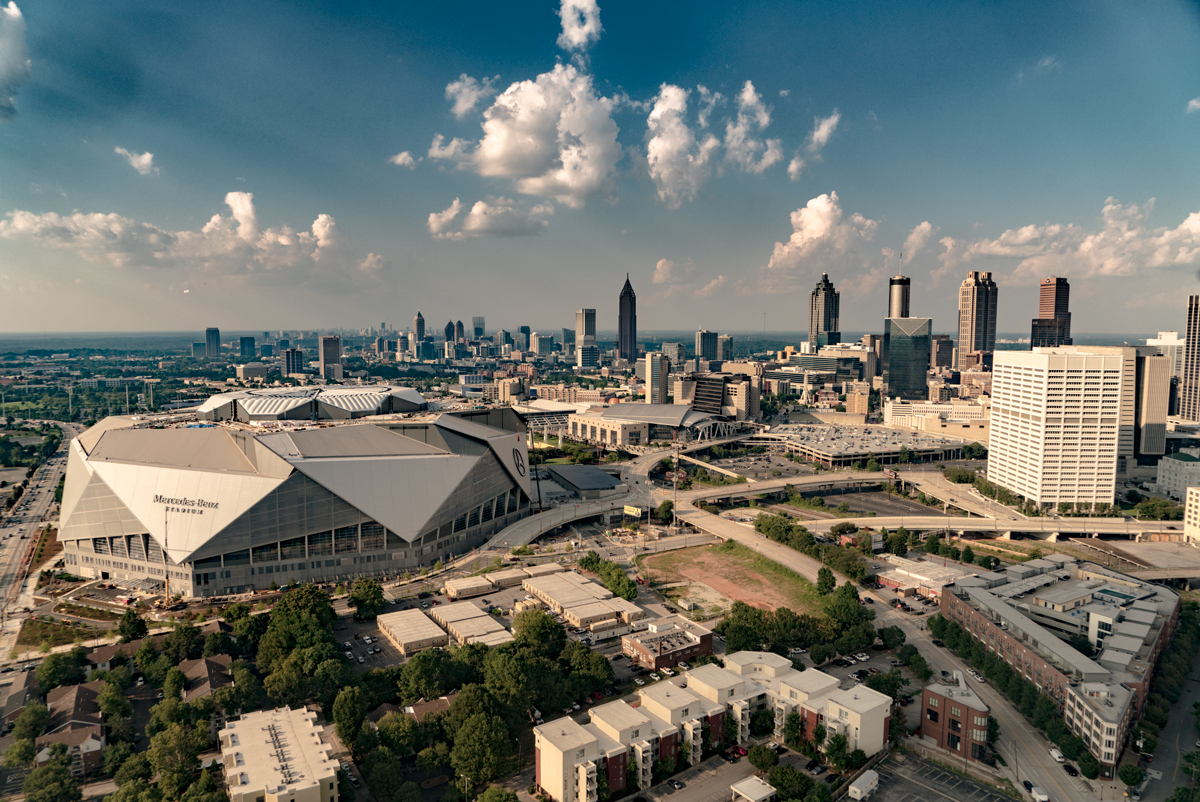

Photograph by Andrea Fremiotti

I. Rite of Passage

When Rich McKay interviewed for the Falcons general manager job in 2003, he made sure to ask owner Arthur Blank if there were any plans to build a new stadium. McKay was coming from Tampa, where he’d been a point person on the construction of Raymond James Stadium, a facility funded entirely by public dollars after the Buccaneers’ owner threatened to relocate the team. The process was bruising, and McKay had no desire to go through that again. New stadiums, McKay told Blank, “take years off your life. It’s very personal.”

“Don’t worry about it,” Blank told McKay. “We’ve got the Georgia Dome. At some point we’ll have to talk about renovating the Dome or replacing the Dome, but that’s years in the future.”

Ten, as it turned out. In the interim, McKay went from Falcons general manager to team president and CEO, finding himself once again not in the business of building a football team, but building them a new home.

Photograph by Andrea Fremiotti

McKay has the wiry body of a long-distance runner, which he is, and when we spoke at the Blank Family offices in Buckhead in late June, eight weeks before the opening of Mercedes-Benz Stadium, he exuded the zen peace of a marathon runner with the finish line in sight. Eight miles to the south, crews were working round-the-clock to ready the stadium for its August 26 opening. Much of the attention in the press and social media was on the vexing mechanics of the retractable roof, but there was just as much happening beneath it—connecting the 4,000 miles of fiber cable, clearing the field so turf could be installed, testing and retesting the 350-ton halo board, hanging art on the walls, hooking up the 1,264 beer taps.

“We’re in a good place,” McKay told me. “I’ve been around this sport a long, long time and it doesn’t always set up this way. When it does, you’ve got to enjoy it. I’m not over our last game”—when the Falcons blew a 25-point lead in the second half of the Super Bowl to lose to the New England Patriots—“but otherwise I’m good.”

The opening of Mercedes-Benz Stadium will mark a rite of passage not just for the Falcons or Blank, but for Atlanta itself. NFL stadiums—new NFL stadiums, that is, with gleaming features and staggering budgets—have become the sine qua non for the cities that claim a franchise. Want to host a Super Bowl? Build a new stadium. Want to ensure your home team doesn’t decamp to another city? Build a new stadium.

Outside of infrastructure—a heavy rail line, a sewer system—a new NFL stadium is invariably the most ambitious and expensive project its host city will ever see. Mercedes-Benz Stadium is currently estimated to cost $1.5 billion; in Dallas, AT&T Stadium was $1.2 billion. Estimates for the new Los Angeles stadium, which will host both the Rams and Chargers, are currently $2.6 billion. For comparison’s sake, the tallest building in Atlanta—the Bank of America tower—sold in 2006 for (just) $436 million.

Benjamin Flowers, a Georgia Tech professor who studies the intersection of sports and architecture, likens the modern-day stadium to the grand churches of Europe, when architects sought to convey the insignificance of man against the awesomeness of the divine.

“I think of stadiums as secular cathedrals,” he said. “It’s hard to be in something that big and vast and not be impressed by it.”

Of course, the cathedrals of Europe were open to all. Although their construction is subsidized at least partially with public money, NFL stadiums are, first and foremost, vehicles of profit for the teams that play there.

Photograph by Andrea Fremiotti

For generations, stadiums in America were built without much thought to aesthetics. They were utilitarian, designed to maximize seating and thus ticket revenue. Little thought was given to frills, or even fan comfort. Lambeau Field, which has sold out every Packers game since 1959, still has just bleacher seating on its main level. But as Flowers writes in his book Sport and Architecture, three developments in the past half-century “fueled a sea-change in their design”—broadcast rights, advertising revenue, and luxury seating. Meanwhile, as 21st-century technology made TV screens bigger and sharper, fans were less inclined to leave their couches. And so it became necessary to dress up the packaging.

Factor in the wealth of the owners themselves. More than half of the 32 NFL owners are billionaires, according to Forbes. Where tycoons of the 19th and early 20th century built museums and funded libraries that would stand for centuries, modern-day NFL owners have more temporal concerns—how to put fans in the seats and how to attract big events, whether it’s the Super Bowl, the Final Four, or the World Cup.

Key to addressing those concerns is the ‘wow’ factor. Perhaps you consider the new 71,000-seat Falcons stadium as modernistic and daring, the architectural icon that Atlanta—whose skyline is so anodyne it serves as the film backdrop for Any City, USA—has always lacked. Or maybe you think it’s garish and incongruous, an exorbitant indulgence. Whatever your opinion, one thing is inarguable: Mercedes-Benz Stadium is, by every measure, monumental.

Photograph by Kevin D. Liles

II. The Big Idea

The call for architects to design Atlanta’s new stadium went out a few weeks before Christmas in 2012. In Kansas City, where he was a founding principal at 360 Architecture, Bill Johnson was not inclined to make a pitch for the job, even though it could mean millions of dollars for his firm. 360, after all, already had plenty of work, and, besides, the firm had just designed MetLife Stadium in New Jersey, which had opened two years earlier.

MetLife Stadium is the home field for two NFL franchises, the Jets and the Giants. This explains its straightforward design: The stadium could not favor one team or the other, so the end result was borne of compromises, big and small. Each team needed its own locker room. The seats are not green or blue (the respective teams’ colors) but gray. The exterior—a stone base topped with aluminum louvers and glass that are illuminated with different colors depending on who’s playing—was described as “traditional yet modern,” which, depending on your aesthetic, could be interpreted as simply boring.

But the Atlanta stadium job was shaping up to be something different altogether. For one thing, Blank wanted his stadium to have a roof that could open and close. Such a feature had been considered for MetLife—a roof means the venue can host indoor events such as the Final Four—but cost concerns ruled it out. Earlier in his career, Johnson had designed the retractable roof at Chase Field, the Arizona Diamondbacks’ ballpark in Phoenix and the first of its kind that covered natural grass. Still, Johnson felt retractable roofs were, from a design standpoint, in a rut. “Essentially, it’s a box with a roof,” he told me. “The roof may close left or right, or sometimes all in one direction, or even park off to the side. But, more or less, that’s it—a stadium in a box.”

Which brings up the second difference between the MetLife job and the Atlanta one—Blank himself. He’d made it clear that the new stadium should be different. Special. Iconic, even—a word that’s been invoked so often in the five years since then that it’s lost all meaning. But, most importantly, the fate of the stadium’s design would be in the hands not of a committee packed with dueling egos and interests, but, practically speaking, of the billionaire who owned the team.

“It would take somebody with his commitment to make this work,” Johnson recalled. Commitment, in this case, meant not just strength of will, but deepness of pockets. Though $200 million of the stadium cost would come from a local hotel tax, the remainder would be Blank and the NFL’s responsibility.

Johnson had just a few months to prep for the presentation, when representatives from the Falcons and the Georgia World Congress Center Authority would measure 360’s ideas against those from four other firms. Instead of working from the bottom up, he told his team to flip their thinking. “Usually, you design the seating bowl, with so many seats, so many suites,” he explained. “Then you design the enclosure and put them together. But it’s never integrated as a concept.” What if, he asked his team, we let the design of the roof inform everything else?

Johnson was inspired in part by the Pantheon, the ancient Roman temple whose interior is illuminated by sunlight streaming in through a circular opening in the domed roof. He imagined a similar oculus over the Falcons stadium, the light painting a spot on the gridiron. But how to seal the opening? Even though he’d designed them, Johnson found conventional retractable roofs ugly. “Why can’t we do something beautiful? And why can’t the way it moves be inspiring and interesting?”

Johnson and his team flew to New York City, where in a series of charettes they brainstormed with the experts at BuroHappold, an engineering consulting firm. One suggestion was a mast, which would anchor cables attached to petals that would converge on closing. Johnson mentioned the idea to Chuck Hoberman, an engineer and artist whose specialty is “kinetic architecture”—basically, structures that are designed to move. Hoberman invented the Hoberman Original Sphere, a geodesic dome of interlacing plastic parts that can collapse in on itself to a fraction of its original size. You’ll find one in every STEM program in America. Hoberman likes a challenge—for one of U2’s world tours, he designed a 60-ton interlocking set of 888 LED displays that expanded and contracted over the stage—but Johnson’s idea was too much.

“You’re out of your mind,” Hoberman told him. Rotating such a massive weight—each petal would weigh hundreds of tons—around a hinge and a post would never work. “You could do it on a tabletop model,” Johnson told me, “but when you got to the scale we’re talking about, it just didn’t make sense.”

Photograph by Andrea Fremiotti

Johnson was facing a reality of physics. “If you blew up a fly to the size of an elephant, it would collapse under the weight of its own body because its legs would not hold its body up. That’s why elephants have these great big tree trunk legs and flies have these tiny ones. It’s about scale and proportion. You can’t do certain things when you get to a certain scale.”

Johnson believed the roof should open and close like the aperture of a camera, but how could the segments pivot away from each other? Software programs called Grasshopper and Rhino helped provide the answer: The segments would move alongside each other, not rotating but each sliding on its own linear track, each track supported by a truss. “That’s the biggest misconception about the roof—that it rotates,” Johnson said. “It looks like it does, but it’s an optical illusion. It does not rotate.”

To further complicate matters, the opening—oval, not circular—meant that each petal was one of three sizes, so when they converged they’d cover the opening neatly. Each petal also had to move at a different speed, since they had different distances to cover.

With the April 16 presentation looming, Johnson knew a computer animation wouldn’t be sufficient to convey the idea; they’d need a scale model with a working roof. Hoberman’s studio constructed the model, getting pieces printed at 3-D modeling shops around the country. From New York City, the model was driven to Atlanta in a van. It was positioned in the corner of the room where 360 would give its presentation, and covered up.

Photograph by Andrea Fremiotti

While the Falcons would build and operate the new stadium, its owner would be the Georgia World Congress Center Authority. A publicly chartered organization, the Authority had strict rules for the selection process, which meant that each of the eight judges—half from the Authority, half from the Falcons—had to score each architect on a 100-point scale. Technically, the designs for the stadium could count no more than 25 points, but the presentation was worth another 25 points. Those two criteria would end up putting 360 over the top.

Johnson wasn’t flying solo. He and his team—which included Hoberman and Erleen Hatfield, a structural engineer and partner at BuroHappold—had gone through dry runs. But what made some of them nervous was whether the scale model, whose roof had been designed to open and close at the push of a button, would work.

Toward the end of their allotted hour, Hoberman invited Blank to press the button. The roof opened. Johnson told the judges assembled around the model that it was important his team demonstrate the roof not just in a computer simulation, but mechanically. “We had to not only prove it to you, but we had to prove to ourselves we could actually do this.”

Within 48 hours, 360 learned it had won the job. Its fee was $35 million.

III. All Personal

Four years ago, when it existed only as a scale model and in fanciful renderings, the new Falcons stadium was estimated to cost $1 billion. But in the first few months of construction, the price tag began creeping up, first by $200 million, then in increments of $100 million. The location required buying—and then demolishing—two churches, and re-routing a city street. Meanwhile, the design itself was evolving. Early renderings called for the massive windows along the concourse to open, like giant louvers. But, as officials learned, the feature would have doubled the cost of the glass system. Moreover, opening the windows would have made it harder to maintain a consistent temperature throughout the building. “You’d think that operable windows would make [the building] more green and environmentally friendly,” Johnson said. “But really, it wasn’t true. Using super-efficient coatings on the glass and reducing the heat gain actually make the building more sustainable than just opening it up.”

Blank had also wanted his team to play on natural grass, and while the retractable roof may have allowed grass to grow, the other events the facility needed to host made artificial turf the only practical surface.

One aspect of the original design was non-negotiable: The roof must open. And close. Quickly and reliably. Johnson had initially imagined the eight petals would be transparent, so even when the roof was closed the sky would be visible. But the glass would have added to the weight, which in turn would have required more steel to support it.

At around 450 tons each, “these petals actually are extremely light,” Hatfield told me. Hatfield is the engineer of record at Mercedes-Benz, which means she signs off on all the drawings and has been flying down from New York City almost every week for the past three years. “If you think about it,” she said by way of contextualizing the 240-foot-long petals, “New York City blocks are about 200 feet long. So these things cantilever a city block. They look like a transmission tower laid on their side.”

As we spoke, the petals were being covered with “ETFE pillows”—essentially, multiple layers of a translucent plastic. Air would be pumped in between the layers, hence “pillow.” Multiple layers of ETFE would not only keep out the heat while letting in the light, they’d also converge to form a water-tight seal, thanks to rubber installed around the edges.

Photograph by Andrea Fremiotti

In any complex building job, the sweat and toil of the architects and engineers tend to be on the front end, and over time the onus shifts gradually to the builders, who are tasked with executing the design. That’s the idea, anyway. On a steamy Friday afternoon in early July, I met with William Darden, the project manager. Darden works out of a series of trailers on Mangum Street, mission control for the stadium project.

Johnson had flown in from Kansas City just to meet me, but Darden was tethered to the stadium, onsite six and sometimes seven days a week. He’d taken to sleeping with his phone. He looked worn out. “It’s a mix of exhaustion and exhilaration,” he said. “There’s no more separation between personal and business. It’s all personal now—for everybody. Everybody is tired, and everybody is going on adrenaline at this point. Normally, I’d be cracking the whip right now. But I can’t now, because everyone is already so all-in. I do a lot more asking, ‘What do you need? How can I help? Let’s remember, we’re all in this together. We win as a team.’ No different from the Falcons or the Hawks or whatever. Hate to be that cliched for you, but it really is the truth.”

Darden first met Blank in the early 2000s, when Blank was looking for someone to oversee the construction of his family offices in Buckhead. Blank met with Darden, then just 42, and the two men hit it off. When Darden learned that his young firm, Darden & Company, had been selected to build Blank’s offices, he didn’t even know what to charge.

Blank explained that he wanted his family offices to be LEED-certified—constructed and operated in the most energy- and resource-efficient manner possible. Under LEED, each initiative wins you points, and the point total determines whether your building is considered Silver, Gold, or Platinum, or merely “LEED-certified.” But the concept was so new 15 years ago that Darden wasn’t even familiar with it. Blank’s Buckhead office ended up being LEED Gold, the first in the Southeast. It was built in part with recycled concrete. To reduce emissions, half the raw materials were made within 500 miles. By collecting rainwater and using low-flow toilets, the office saves 72,500 gallons of water every year. But that was just a warm-up; Blank expects Mercedes-Benz Stadium to be LEED Platinum.

Over the years, Blank returned to Darden’s company again and again to manage projects—renovations at the Georgia Dome, the expansion of the Falcons’ training facility in Flowery Branch, the construction of the Atlanta United FC training facility in Marietta. One of Blank’s favorite expressions is “There is no finish line,” an aphorism that helps explain why Blank didn’t seem as devastated as the rest of us after the team cratered against the Patriots. As he said—both before and since the Super Bowl—the goal has always been to build a franchise that’s competitive consistently.

In practical terms, though, the expression takes on the most significance for the people under him, and especially those in his inner circle, such as McKay and Darden. As co-founder of The Home Depot, Blank opened hundreds of stores and became one of the wealthiest people in the world. At 74, he’s approached building a $1.5 billion stadium with the same relentlessness, expecting no less from his builders. Darden and Blank both tend to email each other late at night, and often the other one is up to respond right away.

“He’s a driven individual,” Darden said. “When his mind gets on something, whoever’s in the way better hop to it. But think about it: How else in the world could you build something like Home Depot, turn the Falcons around, build this thing, if you weren’t driven like that?”

More than frills

Icon by Khoa Tran

Westside renewal

Blank says that the stadium will succeed only if the Vine City and English Avenue neighborhoods around it do. His foundation has pledged $15 million to the Westside Neighborhood Prosperity Fund, one component of which is Westside Works, which has trained 500 residents who together have earned $11 million in wages.

Minority Contracts

As of January 31 this year, $356 million of the stadium-contracted construction had been done through minority- or female-owned firms.

Eco-friendly

Blank wants his team’s new home to be the first LEED-Platinum NFL stadium. Helping them get there? 4,000 solar panels (which can power all the home games); a 680,000-gallon cistern to capture water for irrigation; and low-flow toilets.

Icon by Khoa Tran

Art

That enormous Falcon at the entrance? It’s made of stainless steel, weighs 36 tons, and was shipped by boat from Hungary, the home of its designer. It’s one of 180 pieces of art commissioned by the stadium, which includes Radcliffe Bailey’s “Conduits of Contact,” a mixed-media installation that reflects the movement of blacks to and through America.

Future-Proof

Builders installed 1,800 wireless access points to beef up wifi reception, powered by AT&T. Most points will appear as little boxes tucked under 1,000 or so seats. The digital backbone is provided by 4,000 miles of fiber optic cable, connecting everything from cash registers to the halo board to speakers. Spliced with copper, the lines will also provide power.

Halo Board

At 58 feet high and 1,100 feet around, the “halo board” video screen is 63,000 square feet—covering more than twice the area of Dallas’s monster screen. Depending on camera angles, architect Bill Johnson imagines the sheer size of the video could provide yard-for-yard tracking of the action on the field.

Fifty days from opening, I’d come to Darden to understand the scale of the project Blank had asked him to oversee after it had already begun. I asked about the roof, and he took a breath. “People say, ‘Oh, it doesn’t work.’ It’s not that it doesn’t work. We’ve already moved it three times. It’s just, it’s heavier and it’s putting more load on the bogies and the trolleys. The bogies move [each petal] across one rail, and the trolley rolls with it and keeps it from tipping over into the bowl. So one is sort of the driver and the other is a [stabilizer]. And the weight just kept having to get bigger and bigger as the engineers figured it out along the way.” I recalled Johnson’s fly/elephant analogy, and also his team’s nervousness the day that Blank pressed the button to open the roof on the scale model.

“And that’s the other thing,” Darden said. “The structural engineers should have been out of the conversation six months ago, but they’re still very much in the conversation, and they will be right up to the day we put in the field and put the last piece of millwork in place. Completely unorthodox.”

“Simply because of the complexity of the design?” I asked.

He paused. “If I told you we’re going to put your roof on the day we put your carpet in, you’d go, ‘What? How are you gonna do that? Shouldn’t you already have the roof on so I can get my drywall in and paint it?’ So we’ve had to just make it work.”

At 59, Darden is just old enough to have been in the business before sophisticated software showed architects and engineers that almost anything you can dream of can be built—with enough time and money. He’s not sure that’s a good thing.

Architects, he said, “bring in all the beauty pageant stuff first, and everybody gets all excited, but what I realized is, if you want to build this incredible, complex structure, and you don’t have the ability to follow up with execution, you’re in trouble. And that’s really been an issue here. People put things on paper without really considering the consequences of what it will take to put that in place.”

An example? “Steel,” he said, “was supposed to be in the ballpark of 12,000 tons. It’s about 27,000 tons. Just trust me on this, that’s an exponential pop, even though it sounds like it just doubled. It changes everything. It affected our schedule, our budget, our sanity.”

Instead of relying on six vendors to make the steel, they were forced to hire as many as 36 steel shops. The complexity of the steel itself is illustrated by a photo that hangs outside a conference room in the Darden trailer.

Photograph by Jonathan Tribo with HHRM

In the photo, an ironworker crouches behind a piece of steel probably twice as wide and as tall as he is. The piece is called a connection node, and it’s where multiple beams converge to be fastened. The thing weighs almost five tons, but what’s most striking about it is that its shape is so convoluted it appears more like an abstraction than a functional element. More than a dozen gusset plates jut out from its core. It looks like a Tetris screen that has been infected by a virus. Thousands of pieces of this sort form the latticework 192 feet above the football field, supporting not just the roof, but also the 350-ton halo board videoscreen.

Darden stared at the photo. “So we’ve got 19 megacolumns of concrete. They are just massive. And all of the steel is attached to those 19 columns, and so all that steel that’s so complicated, it’s all cantilevered out.” The 19 columns, he explained, bear the weight of all 27,000 tons of steel.

IV. Critical Paths

On July 25, at a Georgia World Congress Center Authority board meeting, Steve Cannon, the CEO of the Falcons’ parent company, made official to the board what had been rumored for weeks—the roof would stay closed for at least a portion of the Falcons season. No one on the board seemed surprised.

It wasn’t that the roof didn’t work, he explained, but that it wasn’t fully “mechanized”—meaning, that it could open with the press of a button. To host an event with the roof open, stadium officials needed to be able to close it quickly in case of bad weather. Right now the process was taking hours, as engineers took measurements to synchronize the closing.

When I’d spoken with Darden, a colored bar chart at least three feet high was tacked to his wall. The x-axis was time, the y-axis the task—millwork, retractable seating installation, laying the turf. The list went on. Some tasks, Darden explained, have “float” time, but others were on “critical paths,” meaning for it to be completed by deadline, other tasks had to be accomplished first and on time.

“Look at this band of orange here,” Darden said, pointing to one segment in what appeared to be a descending staircase of tasks, each represented by an orange box. “When that box ends, this one starts,” and he pointed to the next task on the next line. “But what if that box goes empty? Then we’re stopped.” To compensate, other tasks need to be compressed or shifts extended. Costs go up.

I asked Darden if wiggle room had been baked into the schedule. “We haven’t been able to do that for well over probably a year,” he said. “Like weather. We have no weather baked in. We just work.”

Photograph by Andrea Fremiotti

The roof, not surprisingly, was a critical path. But as complex and intricate as it is, its functionality was not essential to hosting a football game or a soccer game. So, as Cannon explained, engineers would continue to work on the roof during nights and on days when there were no events scheduled. On game days, the roof would stay shut.

Later that afternoon, I tagged along with board members for a tour of the stadium. It was my second visit in a month. The board members—mostly men, mostly in their 50s and 60s—were almost giggling at the sheer spectacle of the place. So was I. There was the megacolumn, wrapped in an LED screen that could project a player to 100 feet high. Behind it the downtown skyline seemed panoramic through the vast window, which will be curtained for basketball games. McKay, who’d led dozens of these walk-throughs, was pointing out the features with the polish of a veteran docent.

“Any floor, any ticket, you can walk the entire building,” he shouted above the din of hundreds of construction workers still drilling, polishing, hammering. “The luxury suite level is not guarded. That cost us a lot of money, because we had to move the building back” to allow room for both the suites and the concourse behind them.

He pointed at the roof, where the eight petals were closing so slowly their movement was almost imperceptible. To host the Final Four basketball tournament, as the stadium will in 2020, the roof has to be water-tight. “We have to solve for one drop of water,” McKay said.

To emerge from a tour of Mercedes-Benz Stadium is to marvel not at the work that remained, but how much had been done—and how fast. Johnson, the architect, had told me that ambitious stadium projects like this one were on borrowed time. They’re just too ambitious. “I think we’ll end up seeing smaller venues, with remote watching stations all over the city.” If that’s the case, Johnson said, Mercedes-Benz Stadium was a crowning achievement.

“Arthur wanted something unique. And when I talk about icons, I talk about the St. Louis Arch or the Eiffel Tower or the Sydney Opera House or the Disney Concert Hall. This is one of those buildings, and it will always be one of those buildings. And people will come to see it for that, and it will have nothing to do with football.”

This article originally appeared in our September 2017 issue.

![The North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences’ newest exhibit is a [pre]historic first](https://cdn2.atlantamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/04/DD-3-100x70.jpg)