Photograph by Max Blau

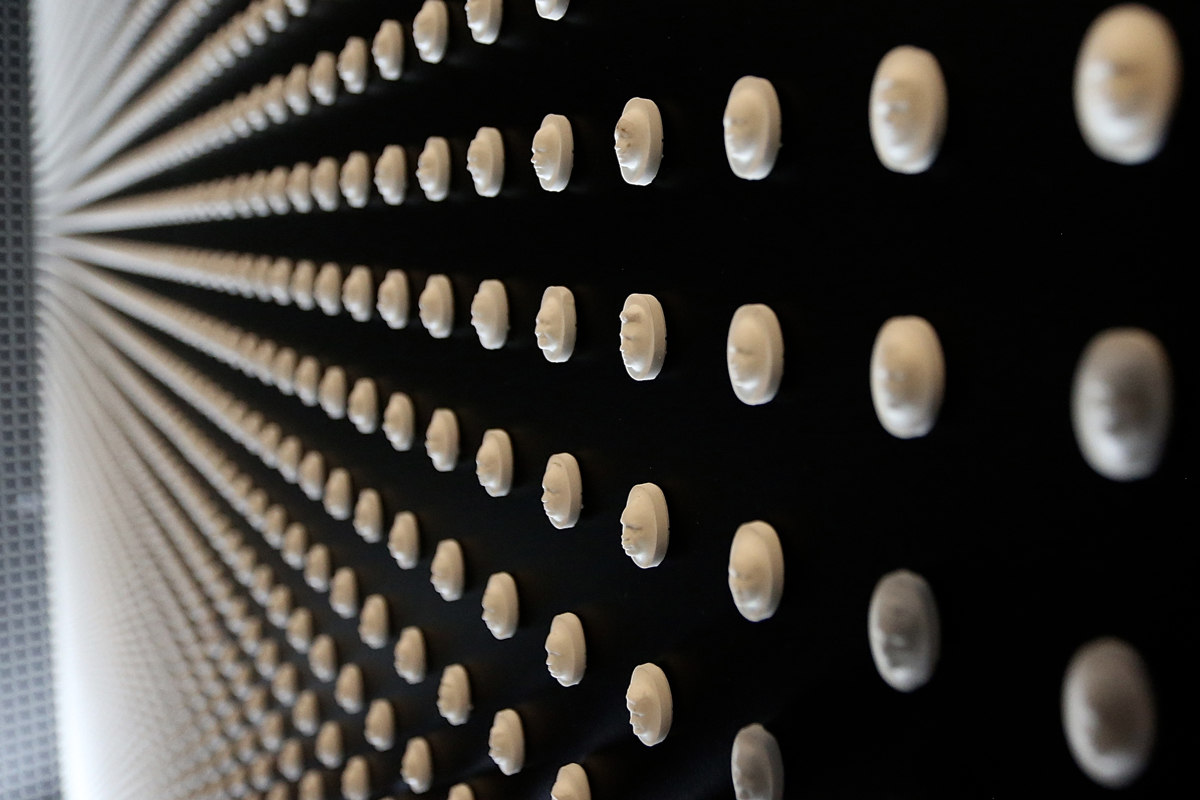

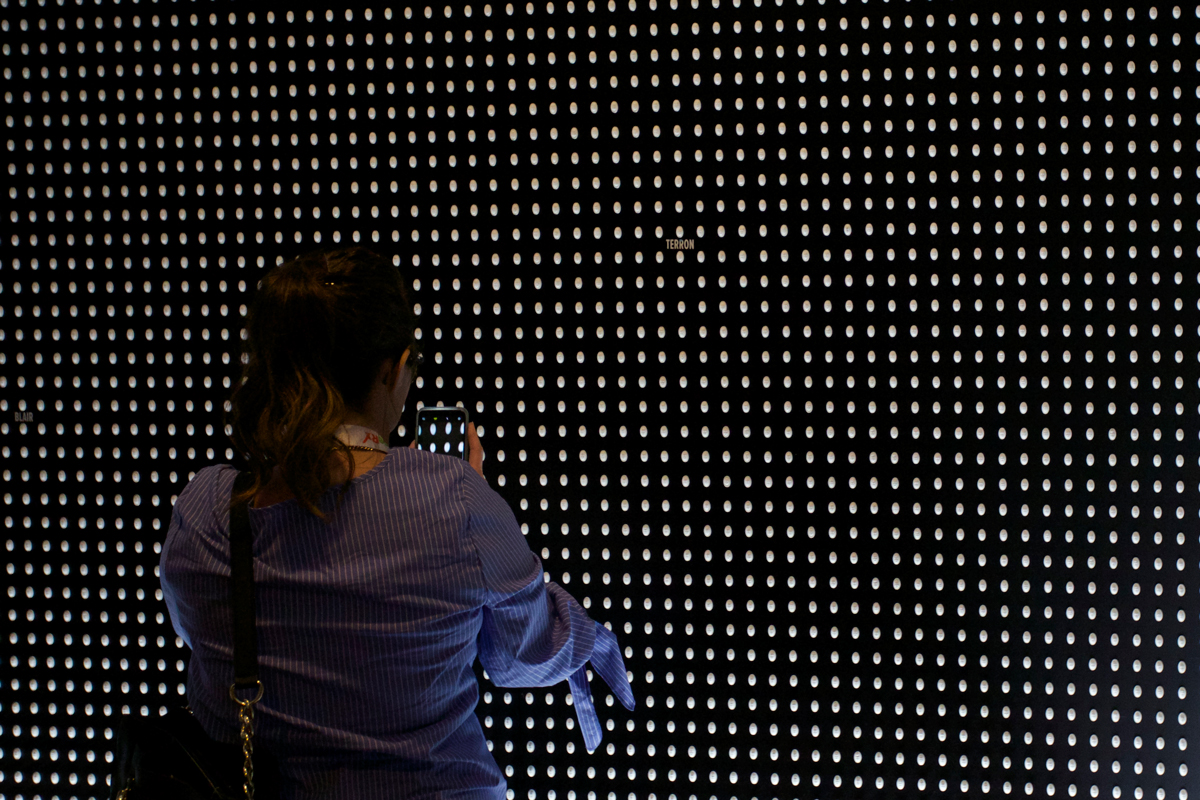

The white pills, fixed on a set of black walls, were perfectly spaced in rows and columns like tiny candy buttons on a giant paper strip. The sight was mesmerizing from a distance; but if you stepped closer, you’d see that each pill had a face carved into it. The thousands of faces were of people who lost their lives to opioids—part of a traveling memorial called Prescribed to Death. One of the faces is in the likeness of Missy Owen’s son, Davis.

Six years ago, the incoming Kennesaw State student was looking for a sleeping aid in his medicine cabinet and found Vicodin. He tried one, grew addicted to the painkillers, and eventually switched to using heroin. In 2014, Davis was admitted to rehab. But a few weeks after completing treatment, he relapsed and fatally overdosed. As the Owen family searched for answers—reading news articles and calling doctors—Missy knew she couldn’t just move on. She had to find a way to do something to prevent other mothers from losing their sons.

“No one really invests in solutions when they don’t have the problem,” Owen says. “If you don’t do research ahead of time, you’re behind the eight ball when it ends up in your lap.”

Photograph by Max Blau

Photograph by Max Blau

This week people from Atlanta to Alaska traveled to the Hyatt Regency for the 2018 National Rx Drug Abuse and Heroin Summit, the country’s largest conference devoted to the opioid crisis. In a sea of nearly 3,000 doctors, drug users, sheriffs, and officials—including former President Bill Clinton and Surgeon General Jerome Adams—Owens was among the legion of Georgians who spoke on panels, presented research, and handed out t-shirts and tote bags filled with information about rehab facilities in hopes of driving down opioid deaths.

“American life expectancy has declined two years in a row—unheard of since 1960s,” said Dr. Anne Schuchat, principal deputy director of the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “[This is] the public health crisis of our time.” Opioids killed 42,000 Americans in 2016.

Attendees spent the conference debating the best ways to tame the epidemic, including better treatment options and smarter prescribing practices. Georgia U.S. Rep. Buddy Carter, the only pharmacist in Congress, called upon his profession help stop the “rogue doctors” who overprescribe prescription pills. And Dr. Patrice Harris, a former Fulton County health director who’s now chair of the American Medical Association’s Opioid Task Force, preached the importance of carrying naloxone, the opioid reversal drug often referred to by its brand name Narcan. Some advocates like David Laws—whose daughter Laura, a 17-year-old North Atlanta High School student, fatally overdosed in 2013—are continuing to push schools to stock up on naloxone as well.

Photograph by Max Blau

To see the effects of prescription opioids—which contributed to more than half of Georgia’s nearly 1,000 opioid deaths in 2016—look no further than the Atlanta V.A. Medical Center. Emory University-affiliated psychiatrist Karen Drexler, who works with the V.A., warned that opioids can “hijack a part of our brain” that determines what’s most important for survival. As some veterans have grown addicted to opioids, the need for drugs overrides other needs like food or safety, she said. To help overcome opioid addiction, Drexler said, patients should be steered toward either methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone—often referred to as “medication-assisted treatments”—to achieve long-term recovery.

It’s not just patients at risk of opioids—but doctors, too. Dr. Paul Earley of the Georgia Professionals Health Program discussed how weekly “Caduceus” meetings bring together 75 physicians to talk about their substance use issues. Between those meetings, plus a combination of inpatient rehab and constant screenings, nearly three out of four doctors who go through the specialized program remain drug free after five years. Along the way, Earley said, the doctors are able to keep practicing medicine instead of losing their licenses.

As synthetic opioids like fentanyl, a drug so potent that only a handful of grains can prove lethal, have become a bigger threat, CDC epidemiologists said they’re now tracking the spread of those drugs to help avoid clusters of overdoses, such as the one that killed six people in Macon last June.

While Georgia’s opioid death rate is still rising, the National Safety Council graded the state as one of the best when it came to strengthening opioid-related laws and regulations. The broader response also includes parents like Owen, who after looking for solutions decided the best way to honor her son was to open an “after-care” center for drug users in recovery after they complete treatment. Every month 3,500 people come to the Zone, a 21,000-square foot facility in Marietta, to attend group therapy sessions, learn how to use naloxone, and hang out other friends who are trying to quit drugs. Owen’s hope is that, by creating the community that Davis lacked, she’ll eventually see fewer faces on engraved those pills.