Bruce McArthur: Toronto serial killer destroyed gay safe space

- Published

For years, there were whispers in Toronto's gay community about a serial killer stalking the community. Now that one of their own has pleaded guilty to the murders of eight missing men, they wonder why the police didn't act sooner.

In a small park in the heart of Toronto's Gay Village, about 200 people assembled in the snow to mourn the victims of an alleged serial killer.

Many wore armbands painted with the words "love", "heal", "rise", "grieve". The words were later used in a call-and-response between organisers and the large crowd.

"Today we grieve," they said, and the word echoed back from the crowd.

"Today we resist. Today we heal. Today we rise. Today, of all days, we love."

A year later, those names were read aloud in a different kind of call-and-response, as Bruce McArthur, 67, pled guilty to eight counts of first-degree murder.

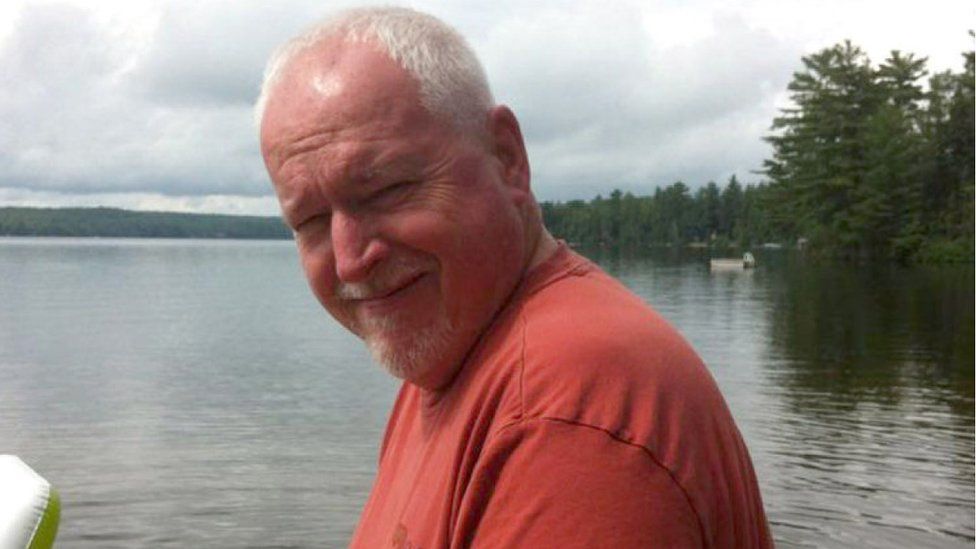

Who is the accused?

McArthur had grown up in rural Ontario and married a woman in the 1980s.

He knew he was gay from a young age, but tried to ignore it, court documents for an assault charge would later reveal.

The grandfather and father of two came out in his 40s after abruptly leaving his family in Oshawa and moving to Toronto, where he became a regular in the Gay Village.

At Zipperz, one of the bars frequented by many of his alleged victims, he could often be found sitting at the bar, having a drink or chatting up a fellow patron.

"I used to refer to him as 'Santa'," Zipperz owner Harry Singh told the BBC. With a white beard, a hefty belly and a twinkle in his eyes, McArthur even worked as a mall Santa one Christmas.

Few people knew of his dark side. In 2003 he was given a two-year conditional sentence for assaulting a male prostitute with a metal pipe.

As part of his sentence, he was required to stay away from male prostitutes, the Gay Village and refrain from using amyl nitrite, also known as poppers.

He was close with several of his landscaping clients. Karen Fraser even let him store tools in her shed on her property on Mallory Crescent.

Police later discovered the remains of several bodies in plant pots on the property and in a nearby ravine.

Fraser said he gave no hint as to what kind of man he really was. He was energetic and joyful, loved plants and doted on his grandchildren.

"As I see it, the man I knew didn't exist," she says.

The shock of discovering that her cherished home had been turned into a serial killer's graveyard has worn off. Now, preparing for his sentencing, Fraser says she has nothing to say to him.

"I'm not big on forgiveness, I'm not big on closure. Terrible things were done," she says matter-of-factly.

Who are the victims?

McArthur's arrest last January had confirmed the worst fears of many in the Village, who for years had whispered that a serial killer might be targeting their community.

"Too many people for too long in our community have been lost," said Troy Jackson, who hosted the community vigil.

Located at the intersection of Church Street and Wellesley Street, Toronto's Gay Village has been the city's enclave for the LGBT community since the 1960s.

But it's been more than a neighbourhood - a home away from home for many who may feel marginalised because of their sexuality.

Many of McArthur's victims were immigrants from South Asia or the Middle East who were not out to their families.

The Village was supposed to be their safe place. Instead, it became a hunting ground.

According to his guilty plea, McArthur killed:

- Skandaraj Navaratnam, 40, over Labour Day weekend in 2010

- Abdulbasir Faizi, 42, in December 2010

- Majeed Kayhan, 58, in October 2012

- Soroush Mahmudi, 50, in August 2015.

- Kirushna Kumar Kanagaratnam, 37, in January 2016

- Dean Lisowick, 47, in April 2016

- Selim Esen, 44, in April 2017

- Andrew Kinsman, 49, in June 2017

Unanswered questions

Police have not said how Bruce McArthur became a suspect in the killings.

He was known to have been in a sexual relationship with Kinsman, and there was video surveillance footage of Kinsman getting in his car on the day he went missing.

Rumours about someone targeting the community began when Skandaraj Navaratnam disappeared from Zipperz on Labour Day weekend in 2010.

Known as Skanda to his friends, the 40-year-old had moved to Canada from Sri Lanka in the 1990s and quickly settled into a comfortable routine in the Village, where he easily made friends.

"His laugh was just ridiculous," Jodi Becker, a bartender at Zipperz and close friend of Navaratnam's, told the Toronto Star after he went missing. "If Skanda started laughing, everybody started laughing, even if nothing was funny."

More victims went missing, and in 2012 police launched a task force to investigate, only to shut it down 18 months later.

Then in June 2017, Kinsman's disappearance sparked a community-wide search and rekindled rumours of a serial killer in the gay village.

Soon after, police launched a second task force, to look into both Kinsman and Esen's disappearances.

But as late as December that year, Toronto police were publicly saying there was "no evidence" of a serial killer.

The denial has damaged an already fragile relationship between the Toronto LGBT community and the police.

Unanswered questions still haunt Haran Vijayanathan, executive director of the Alliance for South Asian Aids Prevention, who has been speaking on behalf of many of the victims.

He successfully called for an independent inquiry - which is still ongoing - into how police handle missing person investigations.

If police had paid more attention, Vijayanathan told the BBC last February, "you can't help but wonder if the lives of the other men who passed or are missing could have been potentially saved".

"Those are the 'what ifs', and 'ands' we have to contend with."

With additional reporting from Jessica Murphy

- Published29 January 2019

- Published29 January 2018

- Published19 January 2018

- Published8 February 2018