At Grievous Gallery, Visitors Discover the Magic of Breaking Things

A Salisbury couple and their gallery help people smash through their pain

IT'S BEEN A ROUGH DAY for Kristin Walker Morgan—a rough year, really—but she puts on a chipper face as she steps into Grievous Gallery in downtown Salisbury a little before 7 p.m. on a Saturday night.

It’s her first visit. Her two kids, ages 11 and 16, were supposed to join her for this early Mother’s Day outing as they all navigate the choppy waters of separation, divorce, and their dad’s remarriage. But their afternoon ended with changed plans and the kids going to Dad’s house instead. So Morgan has come alone, ready for a serious emotional release—the kind when you grab something breakable, fire it across the room, scream, and cry. That is what Grievous Gallery provides: A place where visitors pay money to break things.

“I need a break,” Morgan tells Grievous Gallery co-owners Elysia and Tim Demers. “Literally. I need a break.”

Elysia Demers listens with warm eyes and encouraging words. As Morgan spills the story of what brought her in today, her breathing deepens and her voice calms. She opts for the $50 package, which includes dozens of empty beer, wine, and liquor bottles and as much time as she needs to write on them with a Sharpie. Then she will smash them—with musical accompaniment—in a room the size of a two-car garage. (The $25 package includes fewer bottles. The $75 “Thanksgiving Dinner” comes with four full place settings to smash.)

Tim Demers gets to work setting up the “break room,” and when he comes back to the lobby for Morgan, he congratulates her: “You know how you say there’s a time and a place for everything? Guess what? You’re here! You’re being good to yourself today, and that’s awesome.”

***

TIM AND ELYSIA ARE CALM and cheerful today, but they know what it’s like to feel so angry and hopeless that there’s nothing left to do but scream and cry. Their journey to opening Grievous Gallery started with a motorcycle accident that brought Tim within an eyelash of death on December 12, 2012. (“Twelve, twelve, twelve,” Elysia points out.)

A motorcycle mechanic, Tim was installing a clutch on a Kawasaki KX60. When he took it for a short test drive in the circular drive in front of the shop, he didn’t wear a helmet because he wanted to hear the motorcycle’s engine. Within seconds, a dangling strap he’d forgotten about wrapped around the bike’s front axle and catapulted him over the handlebars and onto the asphalt.

His skull cracked. Elysia, who was in the shop, ran outside and held her husband’s head together as they waited for the paramedics. A helicopter took Tim to Carolinas Medical Center, where he spent 11 days recovering from the head injury, seven broken ribs, a collapsed lung, and a broken collarbone.

Within a few weeks of his release from the hospital, Tim was dazed and forgetting words. He started having seizures. Elysia was scared to leave him alone, so she cut her hours at work. Without a steady income for either of them, she resorted to selling gold jewelry and asking her mom for help paying bills for themselves and Tim’s three children. They slept on the floor of an acquaintance’s vacant house for nearly four months.

They cobbled together enough money to buy a $17,500 teardown home for sale on Jackson Street in downtown Salisbury, installed space heaters, and made it just livable enough to move in shortly before Christmas 2013. Physical and vocational therapy helped Tim recover his balance and improve his cognitive abilities, but he was still at home, unable to work, drive, or tackle the mountain of home improvement projects that needed to be done.

Elysia was exhausted from holding it all together. One day, she reached a breaking point. Tim was being uncharacteristically irritating while she cleaned the kitchen. She grabbed a cookie sheet and started banging it on the island. She banged it until the pan was useless.

“I’ve been trying to get you to do that for months,” Tim said.

A few weeks later, they borrowed a friend’s beach house on Emerald Isle. While it rained all week, they sat and talked. Tim told Elysia about a dream he’d had as a kid in which he was handed marble vases and told to smash them, and as he did, each vase got lighter.

What if there was a place where people could go to get their anger out? Tim asked. A Google search revealed that “rage rooms”—places where people took sledgehammers to cars and threw things at TV screens—were already a thing. They wondered: What if we make ours a place of healing?

***

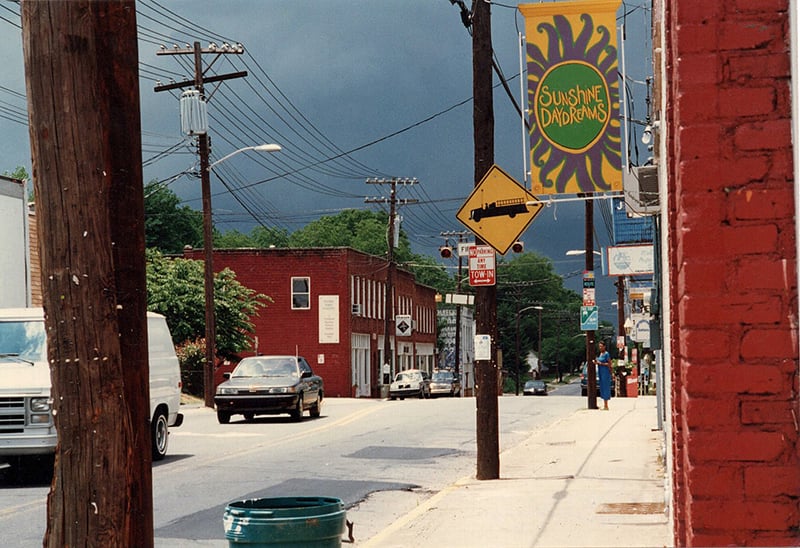

THEY TOLD A SALISBURY BUSINESSMAN about their plan, and he invested $5,000 to get them started. They rented an old warehouse downtown big enough to hold a break room and art and community event spaces, and opened their doors in September 2016. (They’ve since moved to a larger space nearby.)

Other “rage rooms” opened across the state, like House of Purge in Charlotte, where customers can use sledgehammers to bust out car windows, bash guitars, and smash printers. But the Demers’ approach is simpler: Customers stand on one side of a long bar that holds glassware—mainly bottles donated from local bars and restaurants. Tim plays the music of customers’ choice on the sound system, hands them pairs of safety glasses and Sharpies, and steps out of the room. Customers hurl the bottles and dishes over the bar and into a space the Demers designed to resemble an outer space-themed trash compactor.

Tim and Elysia have witnessed moments of breathtaking grace and pain: Parents of a murdered child came to grieve. Glass fragments with the word “rape” appear often, as do “cancer,” “trapped,” “addiction,” and “not enough.” (They periodically pack up glass shards—“emotionally charged media,” Tim calls them—and send them to artists.) One night, a wife stood beside her husband and wrote, “You’re cheating,” on a plate before she smashed it. Parents bring in teens who have cut themselves or suffered through bullying. Often, people emerge and fall into the Demers’ arms. “We’re not therapists,” Elysia says, “but we can tell people, ‘It’s OK to feel this way.’”

LOGAN CYRUS

Customers like Kristin Walker Morgan (middle) break items as a form of stress relief.

Rowan County District Court Judge Beth Dixon has taken a juvenile court counselor and a fellow judge to break glass at Grievous Gallery when the weight of the issues they carry in court gets to be too much. Dixon takes her own four adult children there, too.

“There are coping mechanisms that you just need to get these emotions out,” she says. “We’re in the middle of this huge national discussion about mental health and suicide awareness and substance abuse issues, and these folks are doing something about it.”

On this Saturday, Kristin Walker Morgan cues up David Bowie and Kid Cudi on the sound system as she grabs bottles by their necks and hurls them over the bar. At first, she dances happily to the music and claps when the bottles smash. Her mood turns serious and angry. Then she starts to cry. Several bottles later, with Bowie’s “Heroes” playing, she’s pumping her fists in the air, energized and satisfied.

By the time she emerges from the break room, she’s calm. She thanks the Demers for helping her through a rough night. As she walks out onto dark West Bank Street, she vows to be back—next time with her kids.

CRISTINA BOLLING has reported on Charlotte’s immigration, arts, and popular culture scene since 2000 and this year won two writing awards from the Society for Features Journalism.