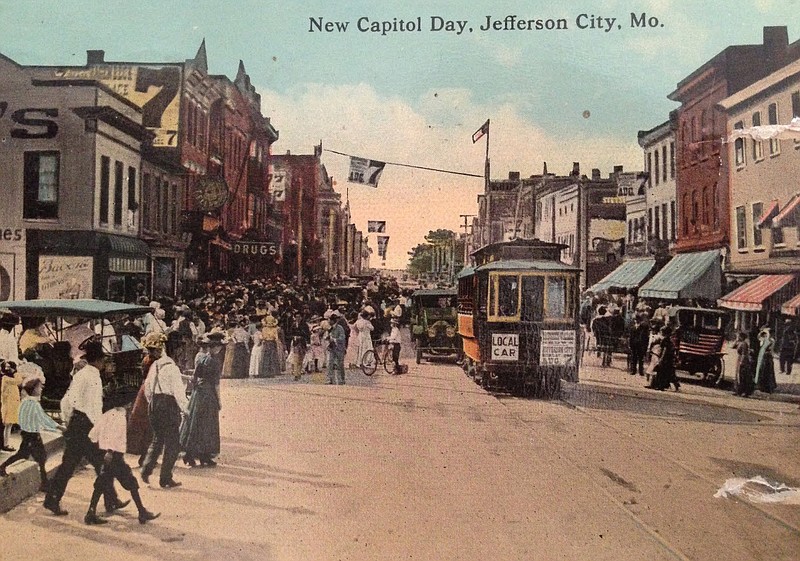

Downtown Jefferson City was crowded and festive on that Monday, April 1, 1911. It was the inaugural ride of the city’s streetcar, and people came from all corners of the county to help the city usher in a new wave of 20th century public transportation.

Jefferson City was still largely a horse-powered city in 1911, when only the wealthy could afford the newly introduced “horseless carriage.” Those early cars were made by hand, pricey and less reliable than the family horse.

In the meantime, during its years of operation from 1911-34, the streetcar provided an easy commute for downtown workers and expanded the city’s reach into the suburbs. With this access, the city’s residential borders expanded east and west along the streetcar’s route.

The streetcars were privately owned by the Jefferson City Bridge and Transit Company. The company’s president, Thomas Lawson Price, and board members of the “J.C.B.&T.” were on that inaugural trip along with Mayor John Heinrichs, members of the City Council and various other dignitaries. Price was the grandson of the city’s first mayor by the same name, Thomas Lawson Price.

The west end of the original route was at the intersection of West Main and Bolivar streets where the pillars for that first bridge across the river built in 1896 still stand on the south bank. It went east on West Main from Bolivar to Broadway, turned south to High, then east to Monroe, north to Main (now Capitol), east to Adams, then west again on High, making a loop and returning to Broadway then Bolivar. Within three years, the route was extended from Bolivar on West Main to Vista Street (almost to Dix). Going east on High from Adams, it was extended to Ash, then south to McCarty and east to Clark where it turned south and terminated at the intersection of Moreau and Moreland. A spur at Bolivar and West Main went north across the Missouri River bridge to the Missouri, Kansas & Texas railroad depot (M.K.&T.) in North Jefferson City, transporting passengers, mail and baggage from the trains. Another spur located in the Millbottom just east of what is now Red Wheel Bike Shop took the cars to the trolley roundhouse and service shed next to the railroad.

The cars were powered by overhead electric lines. There were four cars in that first fleet, and each seated 20 passengers on two long benches that ran the length of the car. But 20-30 more passengers could stand and hold on in the middle aisle. The cost was $0.25, and they appeared every 15 minutes. To reverse directions at each terminus, the original cars were rotated on turntables. Later, these cars were replaced with “double-enders;” the conductor would move to the other end of the car and reverse the car’s direction without having to rotate it.

The superintendent of the lines was J.C. Johnson, but the man who kept it running on schedule was Henry Beck. Beck oversaw maintenance of the lines for much of its years of service. The initial crew of up to 25 motormen and machinists were paid $1.75/day for 10-hour shifts that operated seven days a week.

The streetcars of Jefferson City added impetus for the development of east and west end neighborhoods; Clark and Moreau, West Main, Boonville and streets connected to those. But as buses were introduced and motorcars became more affordable, the need for the streetcars declined. The purchase of the J.C.B.&T. Company by the Missouri Power and Light Company and also the sale of the bridge to the state of Missouri was the beginning of the end of the streetcar transit service. By 1934, the city railway system was abandoned, and the tracks removed.

Recent street repairs in the 300 block of East High street uncovered some artifacts from that old rail bed. Some of these artifacts were presented to Mayor Carry Tergin, who has them on display at City Hall to memorialize this nugget of Jefferson City history.

Jenny Smith is a retired forensic chemist from the Missouri Highway Patrol Crime Lab and former editor of Historic City of Jefferson’s Yesterday and Today newsletter.