The 2016 election was marked by the popularity of Donald Trump with voters in Midwestern states like Iowa and Minnesota, which had voted for Barack Obama in 2012. To the south, Missouri has trended from a purple to a “deep red” Republican state since the early 2000s. Michael A. Smith takes a close look at Iowa and Missouri, states which have experienced economic shifts in recent years which mirror the rest of the US. He writes that the rise of the Democratic Party as one which represents the urban professional class may further alienate voters in the states’ rural areas and small cities who tended to vote for Trump.

The 2016 election was marked by the popularity of Donald Trump with voters in Midwestern states like Iowa and Minnesota, which had voted for Barack Obama in 2012. To the south, Missouri has trended from a purple to a “deep red” Republican state since the early 2000s. Michael A. Smith takes a close look at Iowa and Missouri, states which have experienced economic shifts in recent years which mirror the rest of the US. He writes that the rise of the Democratic Party as one which represents the urban professional class may further alienate voters in the states’ rural areas and small cities who tended to vote for Trump.

- This article is part of our Primary Primers series curated by Rob Ledger (Frankfurt Goethe University) and Peter Finn (Kingston University). Ahead of the 2020 election, this series explores key themes, ideas, concepts, procedures and events that shape, affect and define the US presidential primary process. If you are interested in contributing to the series contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (p.finn@kingston.ac.uk).

In order to understand the politics of Missouri and Iowa, we need to begin with the two longest rivers in North America, the Mississippi and the Missouri. The Mississippi river begins in northern Minnesota, while the Missouri’s headwaters are further west, in the Montana mountains. Both rivers flow through the northern US Great Plains, joining just east of downtown St. Louis. These two, along with a network of other waterways helped grow a mighty industrial and agricultural economy, encompassing many rural communities and small cities along with larger metropolitan areas including Minneapolis-St. Paul (the Twin Cities), St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha, and the “Quad Cities” on the Iowa-Illinois border, home to the storied John Deere tractor company.

In recent times, these states have experienced shifts that mirror the nation and the world. White collar, information economy businesses thrive in the metros, particularly the Twin Cities. While much smaller, Des Moines has a surprisingly strong professional sector, too. College towns like Iowa City, Ames, and Columbia are also showing strong growth, often ranked among the country’s most “livable” cities. Meanwhile, industrial communities like the Quad Cities have struggled to keep up with international competition, automation, and the growth of non-union manufacturing in the American South. St. Louis and Kansas City are a mix of industrial and post-industrial, with St. Louis being the harder hit of the two by the decline of traditional, unionized US manufacturing. On the other hand, Southwest Missouri has become a thriving tourist and retirement destination. Centered on Springfield and Branson, it is particularly popular with older, white, evangelical Christians from the Midwest and South, whose in-migration makes the state more Republican.

Welcome to Obama-Trump country.

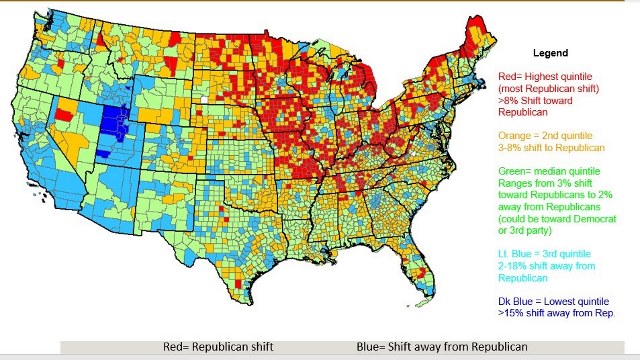

I made Figure 1 below using Arc-GIS and elections data from Politico and the New York Times. It shows party-to-party shifts between 2012 and 2016. A red or orange shift means the county voted more Republican in 2016, while blue means more Democratic. Data is adjusted for population as per U.S. Census estimates. A quick glance shows that the corridor running from Minnesota, through Iowa to Missouri is the epicenter of America’s Obama-Trump voters. At about six million nationwide, Obama-Trump voters backed Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012, and Donald Trump in 2016. They outnumber their counterparts, Romney-Clinton voters, by about two to one. Obama-Trump voters are the swing voters who determined the outcomes of the last three Presidential elections. This map may not tell us who these voters are, but it can certainly tell us where they live.

Figure 1 – Party-to-party shifts by county, 2012-2016

There are large concentrations of Obama-Trump voters around the Great Lakes, in states like Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan, accounting for many electoral votes. But in terms of percentages, the biggest swings from Obama to Trump are actually found in the northern Mississippi River corridor, with many counties featuring double-digit shifts from Obama support to Trump. This can be easily overlooked since only Iowa “flipped” from one party to the other in 2016.

However, Minnesota’s Democratic majority dropped from a comfortable eight point win for Obama to only one and a half percent for Clinton. Meanwhile, Missouri shifted from purple to solid red. In 2008, Republican Senator John McCain eked out a victory in the Show Me State by about two tenths of one percent. Eight years later, Trump won it by nearly twenty points. Yet Missouri voters still act like Democrats on some traditional, lunch-bucket issues. A few years ago, the state’s Republican legislators passed an anti-union “right to work” law banning the closed shop. When it was placed on the ballot via petition initiative, Missouri voters rejected right to work and sided with unions by a margin of two to one. The state’s voters have also used the initiative to pass a higher minimum wage.

“50149-St-Louis” by xiquinhosilva is licensed under CC BY 2.0

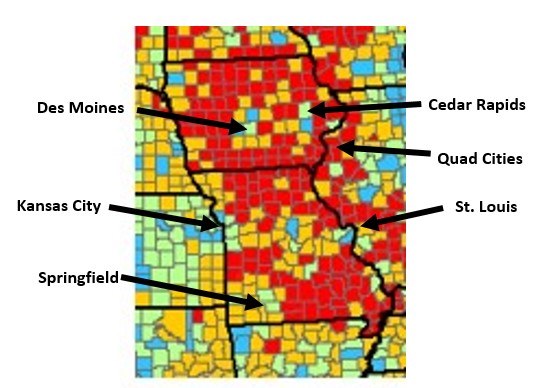

It is important to note where these shifts toward Trump did not occur: the region’s largest cities. In Figure 2, the map zooms in on Missouri and Iowa (Rubrick Biegon of the University of Kent took a close look at Minnesota earlier this month). These states’ largest cities did not shift toward the Republicans in 2016. St. Louis, Kansas City, Springfield, Des Moines, and Cedar Rapids, along with their suburbs featured little to no Republican shift. All of these metros except Springfield are Democratic strongholds, while only the Quad Cities featured a strong move to the red. In addition, there was only slight turnout decline in these larger urban areas, not nearly enough to explain the huge, statewide swings from Obama to Trump.

Figure 2 – Party-to-party shifts by county in Iowa and Missouri, 2012-2016

The shift came in the smaller cities and rural areas. In many cases, this occurred because Trump won counties that had voted for McCain and Romney, by a margin much larger than those other Republicans had won them. Many of these counties did not “flip,” rather, they saw their Democratic minority collapse. Hillary Clinton’s campaign was relatively traditional, focusing on candidate appearances, media buys, and Get Out the Vote drives in the larger metropolitan areas that form most of the Democratic Party’s base these days. This may have been a mistake: the shift in Obama-Trump country came mostly in areas that voted Republican in 2012. It was the collapse of the Democratic minority in these smaller cities, towns, and rural areas that explains the shift.

What caused this collapse? It is likely to have been a number of factors. Smaller cities like St. Joseph, Missouri (located a few counties north of Kansas City) and the Quad Cities are hard-hit by shifts in manufacturing. Trump’s embrace of tariffs and opposition to illegal immigration may have played well with these voters. For his part, in 2009 President Obama supported a bailout of the US auto industry, saving an estimated 1.5 million jobs, many in this region. Obama was also tough on illegal immigration, even being labeled the “deporter in chief” before Trump took office with his own, far more extreme plans including the border wall. In addition, Obama ran a more sophisticated campaign than did Clinton, extensively using “microtargeting” techniques to identify pockets of voters outside the usual Democratic base. By contrast, Clinton had a remarkable, personal unpopularity with these voters, and the Trump campaign clearly outflanked her in microtargeting. The voters in question tend to be working-class whites.

Have these Obama-Trump voters become solid Republicans in just a few election cycles? It is possible. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Democratic Party has only solidified its status as the party of the professional class, which just alienates it further from the voters here in Obama-Trump country who live outside the larger metros and the college towns. Yet Joe Biden rarely forgets to remind voters of his close association with Obama, and he appears to have more appeal with working class whites.

This year, Democrats are counting on higher turnout from groups which are solidifying in their support for the party, particularly college-educated women, whose support and increased turnout were critical in flipping many suburban districts, and the House majority, in 2018. But here in Obama-Trump country, they’ll also need to win back some of their old voters to win Iowa, turn Missouri purple again, and build their base back in Minnesota. This will also make a huge difference in the Great Lakes states, which have more electoral votes. To do this, Democrats will have to move their appeal beyond the larger metropolitan areas.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2zV0tQd

About the author

Michael A. Smith – Emporia State University

Michael A. Smith – Emporia State University

Michael A. Smith is a Professor of Political Science at Emporia State University. His scholarship focuses on civic engagement and voting laws. His research on voting laws analyzes data on voter turnout changes in states with photo ID and proof-of-citizenship voting laws.