Art In Conversation

PIERRE BURAGLIO with Raphael Rubinstein

“My ideal is to capture reality at an angle, to surprise it, to surprise myself.”

During the “events” of May 1968, when students and workers brought the French nation to a standstill and almost toppled the government of Charles de Gaulle, the streets were filled with punchy, quickly produced posters and flyers. Most of them issued from the print studio at the École des Beaux Arts, renamed Atelier Populaire by the students and artists who had occupied it. Pierre Buraglio, then 29, was one of the artists who volunteered to work the Atelier Populaire, but, as he has subsequently explained, he never designed any posters himself: his contribution was limited to helping with the lithography and silkscreen process. The following year, unable to reconcile his political convictions with his artistic practice, he stopped painting and took a fulltime job operating a rotary press in a factory that printed mass-circulation magazines. At the time, many leftist intellectuals in France chose to take factory jobs in order to organize and to live in solidarity with the working class, a movement best captured in Robert Linhart’s 1978 autobiographical novel L’Établi (translated into English as The Assembly Line). Buraglio’s stance of refusal extended also to turning down invitations to participate in the emerging Supports/Surfaces art movement. Returning to art-making in the mid-1970s, Buraglio gradually emerged as one of the most adventurous and independent French artists of his generation. It’s only in the last few years, however, that his work has begun to attract attention on this side of the Atlantic. Along with his current solo show at the New York branch of Ceysson & Bénétière, he is included in Unfurled: Supports/Surfaces 1966-1976 at MOCAD. A retrospective of his work opens June 8 at the Musée d’art moderne in Saint-Etienne, France. This interview was conducted in French via Skype and translated by the interviewer, with subsequent additions made via email.

Raphael Rubinstein (Rail): As we speak you are getting ready for an exhibition at Ceysson & Bénétière in New York. Amazingly, this will be your first solo show in a New York gallery. But it’s certainly not your first visit to the city. You came here initially in 1963 when you were 24. What was that like?

Pierre Buraglio: I had the impression of being provincial. In comparison with New York, Europe was like the countryside, the provinces. I discovered a megalopolis, a city that I knew only through the cinema and photographs, above all through the cinema. So the first thing was an impression of gigantism. The second impression came from my interest in Afro-American culture. Every evening I went to jazz clubs: The Five Spot, Birdland, the Village Vanguard. I heard Thelonius Monk, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, [Rahsaan] Roland Kirk. That was very positive. Less positive was the fact that my wife’s family, whom we visited, were religious Jews, who weren’t very happy to see me. But even more important than the music I heard, was discovering the best American art of the time, which I hadn’t really understood before. This marked me for all my life. I went to the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, the Guggenheim. At MoMA I saw Cézanne’s The Bather [1885], which many years later I began working on.

Rail: What happened when you returned to Paris? Did things change artistically?

Buraglio: I began painting on newspapers and ordinary paper laid out on the floor, perhaps a little similarly to American painters like Kline. Then, I began making the Recouvrements. In effect, I used sheets of paper to cover up some paintings I’d made in a lyrical, somewhat American style. The paper I used was the type used for offset printing, the same paper used for ads in the Paris Metro.

Rail: Interestingly, this was the same kind of paper being used by the Nouveaux Réalistes like Jacques Mahé de la Villeglé and François Dufrêne, who recuperated advertising posters from the Metro and from the street.

Buraglio: Yes, that’s true. It’s also true that my work has always been nourished by the experience of the street and of daily life. But the fact of covering up one’s own painting introduces something different. Ever since I was a young artist, and still now, a central aspect of my work is the expression of a certain kind of doubt. I’m not a Protestant, but doesn’t Martin Luther always talk about doubt? Well, I made paintings and covered them up. Then came the Agrafages, where I cut up paintings into irregular triangles and stapled these fragments together, more or less as they fell. With both the Recouvrements and the Agrafages, it’s the same doubt, the same putting things into question.

Rail: I am continually struck by your practice of changing materials. Looking over your entire career, it seems that every two years or so you discard one set of materials, one way of working, for a new one. As if after two or three years, you say to yourself, “I’ve made enough of these, let’s see what else I can do.” Looking at the Flammarion monograph by Pierre Wat, the sequence of different works, and the range of materials, is astonishing.

Buraglio: That’s why I never had a big market! I changed too much. One thing obsessed me: I didn’t want to make a trademark image where you could say, “That’s a Buraglio.” I want whatever consistency there is to be seen over a longer time period, and more mysteriously, so that at the end, after I am dead, or after the exhibition in Saint-Etienne [laughs], you will be able to detect a certain style.

Rail: You began showing at the Galerie Jean Fournier when you were in your mid-20s, starting with the 1966 group show, Pour une exposition en forme de triptyque, with Daniel Buren, Jean-Michel Meurice, Michel Parmentier, Simon Hantaï, Jean-Paul Riopelle and Antoni Tapiès. Interestingly, you, Buren, and Parmentier had all studied with Roger Chastel at the École des Beaux-Arts. In 1966, it seemed like you shared something in common. At least Fournier thought so. But soon your paths diverged. Buren and Parmentier went in another direction. Can you talk about that?

Buraglio: Gladly, it’s an important moment for the production of painting in France. Buren and Parmentier, later joined by [Niele] Toroni and [Olivier] Mosset to form BMPT, took the position, by their actions and their discourse, that it was the end of painting. “We proclaim that painting is dead!” It was a position that came straight out of Dada, and from the ultimate consequences of Mondrian, Malevitch, out of a certain kind of nihilism. It was very peremptory and perfectly satisfying to a “modernist” bourgeois intelligentsia. BMPT called themselves “non-painters.” But not me! My position was to deconstruct in order to reconstruct. I haven’t changed. I had and still have the same position as a citizen: deconstruct the society that is based on capital and inequality to create another one.

Rail: One thing that marked Fournier was the presence of both European artists, mostly French, such as Hantaï and Claude Viallat, alongside Americans (mostly expatriates) such as Sam Francis, Joan Mitchell, James Bishop, and Shirley Jaffe.

Buraglio: Jean Fournier not only admitted my paintings into his gallery but supported it for many years. And other artists he showed, like Hantaï and Shirley, appreciated my work. I felt the same about theirs. Works like the first Sam Francis paintings I saw gave me such pleasure, actually more than pleasure, they provided a great intensity.

Rail: I want to quote something you wrote about your relationship to these artists and to the gallery. “At the same time I was fascinated by these painters . . . whose work struck me physically, but intellectually I never subscribed to the ideology that sustained this painting and the gallery itself, a genetic conception of art: Cézanne, Matisse, Pollock.” What was the ideology you rejected?

Buraglio: When I say that I didn’t accept the ideology, I am thinking, first, of the discourse of tautology, of painting as a purely self-reflexive project, sustained by critics like Clement Greenberg, for example. Even though Greenberg came out of the Partisan Review and was a man of the left, he embodied a philosophy that I’d always rejected as idealist, a philosophy in which everything can be explained. The second thing that bothered me was that I never thought that the history of painting was a process of heredity [operation génétique], that there was Cézanne, then Mondrian, then Pollock, and that you couldn’t do anything outside this line. That was absolutely false, because at the same time you had Max Beckmann, who seems as great as Pollock or you had Jean Hélion. I always refused this totalitarian aspect of art.

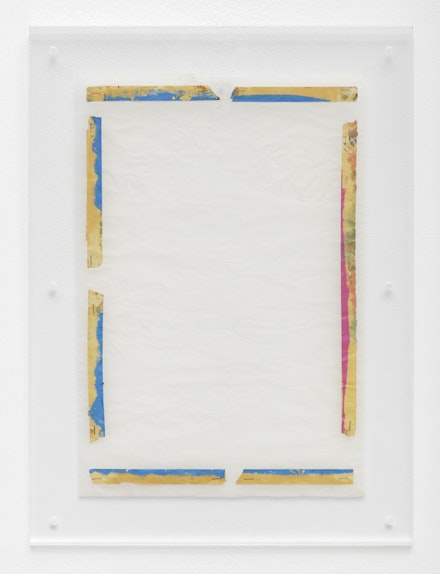

Rail: Jean Fournier’s gallery was always completely identified with painting. In fact, I don’t think he showed any artists who weren’t painters. But your work wasn’t painting, at least in the conventional sense. You used window frames, car doors, masking tape, newspaper pages, cut-up Metro signs. Almost never any canvas, and never any paintbrushes, just the merest traces of paint, say on a window frame or a strip of masking tape.

Buraglio: That’s true, but I was convinced and remain convinced that what I was doing was painting, just not with the traditional means. My preoccupation, my will, was to make painting.

Rail: The continuation of painting by other means, to paraphrase Clausewitz. It certainly helped expand the definition of painting. You were part of a generation of artists who started deconstructing painting in the mid 1960s: Giulio Paolini in Italy, Blinky Palermo in Germany, Richard Tuttle in the States, you in France. This was radical work. Yet I also see the Agrafages, which you began in 1966 as having a relationship to École de Paris abstract painters such as Poliakoff and to the décollage of the Nouveaux Réalistes, and also, of course, to Kurt Schwitters.

Buraglio: Poliakoff? I’m very surprised that you mention him, but I’m happy with the connection to Nouveaux Réalisme and Schwitters.

Rail: I think that even though the Agrafages involve the literal destruction of painting and reject relational composition, there is something at the pictorial level that looks back to artists like Poliakoff. I also believe they look ahead to later artists, to how Julian Schnabel broke up the surface in his plate paintings and how Mark Bradford makes complex paintings by accumulating everyday detritus. After the Agrafages you made the Camouflages, where you created a kind of Mondrian composition with white canvas and camouflage fabric. I see these works as political, particularly because the fabric you used was that of the French Army paratroopers, who were synonymous with violent repression. Did you think of them that way?

Buraglio: No, it was, rather, a discourse on painting. Camouflage is, by definition, a matter of imitation, which poses by the question of mimesis. Yes, I used the camouflage pattern of the paras in a composition taken from Mondrian, but it wasn’t meant to be political art. My political engagement ever since the Algerian War had been in the street, not in the studio. I preferred to take direct action, such as working and organizing in a factory. I thought that the work of painting was something else. But after May ’68, I didn’t see how to make political painting, or any painting, that I could reconcile with my political beliefs, so I preferred to do nothing. I have nothing against “political art” but it was something I just couldn’t do myself.

Rail: In a lot of your more recent work there are explicit references to history (Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Rosa Parks, the First and Second World Wars). I want to come back to that, but I also want to know why, after four years of working full time in a printing factory and being involved in political organizing, did you quit and take up art again?

Buraglio: The truth is I felt a kind of lassitude. And I began to feel the physical and intellectual need to take up my work where I had left it in 1969. There’s an expression of Samuel Beckett when someone asked him why he wrote. “Je suis bon qu’a ca,” he replied.

Rail: “That’s the only thing I’m good for.”

Buraglio: And the only thing I’m good for is painting. I realized it was a necessity.

Rail: When you returned to the studio you began by making works solely out of wood stretchers and picture frames, the Châssis [Stretchers] and Cadres [Frames]. A zero degree of painting.

Buraglio: Actually, at first I tried to make some photomontages in the style of John Heartfield, but they weren’t any good. I was a bit disappointed. I had wanted to do something completely different from what I had been doing before.

Rail: Wow, I’ve never seen these photomontages.

Buraglio: I destroyed them.

Rail: I was surprised that when you cited three artists who most marked your life, along with Gilles Aillaud and Hantaï, you name Bram Van Velde.

Buraglio: It wasn’t for his painting, or for his “touche” as Shirley [Jaffe] would have said. It was Bram’s posture, his position of making a non-productivist art with poor means, his holding back, his failure. He was the contrary of artists who are concerned with succeeding. He rejected the banality of success.

Rail: What about Gilles Aillaud, an artist who is barely known here?

Buraglio: For me the great lesson of Gilles Aillaud was his modesty before the world in the face of reality. He said that one had to leave things as they were. He was always opposed to any kind of formalist art. He embraced distance and modesty. As an artist he was very independent. He had an attitude that was like that of a philosopher. He used to say that he “ruminated” like a sheep. Whatever he painted, whether it was a lion in a cage or a portrait of his wife or a landscape in Brittany, he relied on his great powers of observation. “Leave things as they are,” he would say.

Rail: All your work is marked by what you’ve called “L'économie du pain perdu” [“pain perdu,” literally “lost bread,” refers to the popular dish made with stale bread and eggs, known in English as “French toast”]. For decades, you only used found and recycled materials, and even when you draw or paint you prefer to do so on cardboard or leftover pieces of wood. I think your work is much more “povera” than Italian Arte Povera! What’s behind this attraction for humble materials?

Buraglio: As I said, it was the anti-productionist stance of Bram Van Velde, visible in his gouaches on paper. Equally important was the writing of Beckett and poets like Francis Ponge and William Carlos Williams. I also took something from how the Vietnamese fought against the Americans. For example, I remember reading in Le Courrier du Vietnam how the North Vietnamese used the wings of downed U.S. Air Force bombers to repair their washing machines.

Rail: What about the “Caviardages,” also known as “Les très riches heures de P.B.” where you redact newspaper pages and your own agendas?

Buraglio: The title is ironic, an antiphrasis. It alludes to the Duc de Berry’s famous illuminated Book of Hours. My life certainly wasn’t that of a duke. Every day, after they had elapsed, I crossed out all the appointments in my agenda, which I continue to do. Very depressing. I also busied myself with crossing out, scratching out [biffer] pages of Le Monde, a newspaper I have been reading since I was 16. I should point out that “biffer” is a word used by Michel Leiris for the title of a book of his memoirs, Biffures.

Rail: When I first encountered your book Écrits entre 1962–2007, I was astounded by the quantity of your writing. It’s 400 pages long and there’s a subsequent volume, which I haven’t seen yet, of writings since 2007. That’s a lot of writing for an artist.

Buraglio: My practice in writing is obviously different from a writer’s. There's no intention to make a literary work. I use words to pass on certain ideas, to polemicize and to reflect on my own work, and on the works of other artists. Writing is also an occasion to take sides socially and politically.

Rail: Yet literature is very present in your art. Your titles make references to Leiris, to Ponge.

Buraglio: I was lucky when I was at lycée to have a teacher of French and Latin who gave me a taste for reading and writing. I have read a lot all my life so the resort to writing is natural.

Rail: You have done collaborations with a number of writers, for instance, Marcel Cohen.

Buraglio: As I said, I was marked by a taste for writing and literature, so it was natural that I got to know writers and publishers of my generation, like Marcel or Dominique Fourcade. I enjoy having a dialogue with writers. In our projects the essential thing for me is try to understand their texts and to accompany them. Mine is a secondary work, an attempt to illuminate them in some way, based on a certain reading, a certain understanding.

Rail: For me there are two key words in your work: le refus [refusal] and le vécu [the lived].

Buraglio: Yes, le vécu. When I scored through every word on a page from Le Monde or accumulated used postal envelopes, this was part of a large, more or less expressive artistic [plastique] project. Also the works with doors from a Renault 2CV. The car door as a proposition. The Gauloises packets are also tied to my lived experience. I smoked Gauloises. So did my mother. I owned a 2CV with a woman I loved, etc., etc. And it’s the meeting of the things of the world and a pictorial potential, because the blue of the Gauloises returns to Giotto, to the Quattrocento, to Matisse, because the 2CV door is flat like the surface of a painting. And the 2CV is the most economical of cars. Or when I use enameled metal signs scavenged from the Paris Metro, they are at once part of my daily life and a reference to della Robbia glazed terracottas. These are facts of my life that weren’t chosen by others, and they connect to the feeling I had about the history of painting, in particular the history of Western painting.

Rail: Basing your painting on the everyday stuff of your life is the total opposite of Greenbergian formalism.

Buraglio: [in English] Sure. [Laughs]

Rail: After the factory you began to teach at the École des Beaux-Arts in Valence. Instead of encouraging students to emulate your practice, you sent them to museums to make drawings from art history. You said you never wanted to present yourself as a model for your students. It seems to me that you also don’t want to be a model for yourself. By always changing your work, you can never become your own model. It’s something you refuse.

Buraglio: Yes, that’s it exactly. To renew my life every day, to reintroduce myself, to question myself. It’s a matter of refusing what seems poorly thought out or facile, refusing painting that is commercial, that is what you expect. I adopt an attitude of constant refusal in order to advance.

Rail: One of your most consequential refusals was turning down invitations to participate in the early Supports/Surfaces exhibitions. You also declined Louis Cane and Daniel Dezeuze’s invitation to contribute to the journal Peinture: Cahiers Théoriques.

Buraglio: I am happy, retroactively, to have refused to be part of the Supports/Surfaces group, as narrowly defined, to have stayed outside. And even happier to have refused to participate in Peinture: Cahiers Théoriques, whose excessively obscure texts are today unreadable. My political position being more radical, I quit the very comfortable “ideological front” to work in a factory. I’m glad I made that choice. The differences I had with the Supports/Surfaces artists weren’t primarily artistic. They were political.

Rail: In the 1980s, after working exclusively with found materials, you began to make drawings with motifs from art history. This led to your ongoing “Dessins D’Après” series. Did this grow out of your teaching experiences?

Buraglio: For me it was the first step to get back to drawing, to drawing and painting figures. At first I drew from Poussin, Caravaggio, Munch. Little by little, this allowed me to get to the point where I could draw “après” the world around me, as well as “après” art history.

Rail: And now you are drawing your garden and the buildings in your neighborhood. Another approach to le vécu.

Buraglio: I’m even trying to introduce human figures, notably my father. In treating my own history, you could say I’m making history paintings. Very ambitious! [Laughs]

Rail: So many of your recent works feature architecture. It seems to me that you are very attuned to the built world. I know that your father was an architect.

Buraglio: Yes, and my grandfather was a mason.

Rail: So that’s why there are all these bricks in your recent work! Another recent architectural series is drawings of German bunkers on the coast of Normandy. Looking at them I can’t help remembering that your father became a German prisoner of war in 1940, just after you were born, and you didn’t see him for the first five years of your life.

Buraglio: When my father returned from capture in 1945, he went to work as an architect, helping with the reconstruction of French cities on the Channel—places that had been heavily, even excessively, bombed. I saw the ocean for the first time in 1946 and discovered those bunkers. They are imprinted on my memory.

Rail: The First World War also turns up in the recent work.

Buraglio: In 2012 I was commissioned by the Musée de la Grande Guerre in Péronne, near the Somme battlefield. I responded by drawing and painting World War I objects and uniforms, not always with a definite subject. I approached this project in a pacifist and above all internationalist spirit. Over the past year I have been trying in my studio to look back to my father, first as a soldier, then as a prisoner of war. It’s a way to reconnect with my childhood as a boy without a father in Nazi-occupied France.

Rail: Another recent series of charcoal drawings is titled “Rafistolages.” I’d never come across the word rafistolage before. It seems related to bricolage.

Buraglio: Rafistolage means to repair something with whatever you have at hand. I used it for drawings I made after masters like Rodin and Courbet. I drew them in museums but without looking at the paper, only at the work I was drawing, like Courbet’s Walking Man or Origin of the World [1866]. Then back in the studio I would put together all my numerous attempts, successful or not. There’s obviously a link between this procedure and when I glean poor, used objects for my art. My ideal is to capture reality at an angle, to surprise it, to surprise myself.

Rail: I’d like to come back to jazz. Your passion for the music belongs to a strong French tradition, going back at least to Boris Vian and Francis Paudras. Your love of jazz can be traced in titles like After Midnight, Elégie Pour Chet Baker and, somewhat more subtly, the “SH-Monk” series.

Buraglio: You could add Elégie pour Art Pepper and Now's The Time, after the Charlie Parker composition. The title “SH-Monk” refers to Simon Hantaï and Thelonius Monk. At one point I spent a lot of time with Hantaï and his family, who were all musicians. In this series I used some drop cloths and leftover pieces of canvas that Hantaï had given me to use in my own work. Joining together Hantaï and Monk is at once a provocation and a challenge. Hearing Monk play in New York in 1963 counts for more in my life and in my work than Hantaï’s painting.

Rail: That’s a serious statement.

Buraglio: I am dedicating my New York show to Charles Mingus and Max Roach, those two great musicians, both so involved in the Civil Rights movement.