ArtSeen

Loie Hollowell: Plumb Line

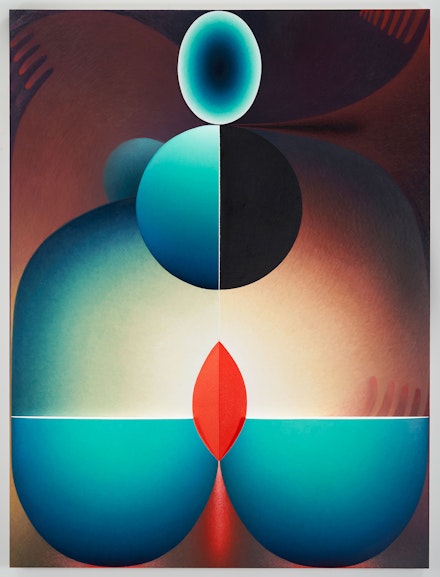

Loie Hollowell, Birthing Dance, 2018. Oil paint, acrylic medium, sawdust, and high density foam on linen mounted on panel, 72 x 54 x 3 1/2 inches. © Loie Hollowell. Courtesy Pace Gallery.

On View

PaceSeptember 14 – October 14, 2019

New York

Body is vessel in the nine new paintings by Loie Hollowell that make up Plumb Line, the artist’s debut show with Pace in New York. With a strong, centrally-placed vertical line as her organizing principle, Hollowell delivers human forms distilled into a succinct vocabulary of curved shapes: bisected disks, almonds, and ovals, plus stacked rows of half-circles crowned by a glowing orb. Each painting, the artist tells us, contains a head, breasts, pregnant belly, vagina, and butt, and in this sense they are overtly autobiographical, as they were produced in the last 18 months during Hollowell’s pregnancy and after the birth of her first child. The paintings also address the body in other, less direct, ways: the dimensions of each work (6.5 by 4 feet) accommodate Hollowell’s height and lateral reach, recalling, for example, Agnes Martin’s self-imposed 6 by 6 foot limit, the largest canvas she could carry by herself. Hollowell’s work implicates the body both thematically and through the embodied experience of space.

The paintings exude a confidence that comes in part from Hollowell’s bold palette of royal blues, blood reds, and umber yellows. Viewers will find a stronger graphic quality here than in her last New York showing at the now-closed Feuer/Mesler Gallery in late 2016. (Only one painting there, the olive-hued Full Frontal (in Green) (2016) closely prefigured the present works.) Gone are the oblique references to landscapes of the American southwest, the atmospheric perspective, and the flattened quality of shallow pictorial space, all of which once allied Hollowell with the creased mountains and undulant flora of forebear Georgia O’Keeffe. Instead, we now find crisp-edged fields of paint—achieved by masking off parts of the canvas with tape—as well as smooth, almost Constructivist, curves of computer-modeled hard plastic that protrude outward from the picture surface. The art historical references so often used to describe Hollowell’s work are still there, but, mostly, these simply look like paintings by Loie Hollowell.

Due to their compositional strength, the paintings read well both in the gallery and in reproduction. Yet Hollowell is at her best when she leverages effects not easily captured by photography, such as the visible brushstrokes, sometimes loose and sometimes tight, that arise from the circular motion Hollowell uses to blend paint. These marks are particularly evident in Milk Fountain’s (2019) luminous downward jets and in the curly fur on either side of Boob Wheel’s (2019) spread blue mounds. The swirling texture of Hollowell’s handling adds volume to matte expanses of beeswax medium mixed with oil paint, seemingly catching hold of and refracting the depicted light that emanates from the work. Equally important are the slender crescents—the flat side of a circle sliced in half—that appear in each of the paintings on display. The artist has lavished considerable attention on these, which she painted with a sponge to produce tiny, gleaming peaks. Seen straight on, this stucco-like texture barely registers, but seen from the side, subtle color gradients appear within or across crescents.

These shifting and unpredictable perceptual effects are crucial to the paintings. Hollowell’s work clearly implicates the body, but by requiring viewers to reposition themselves from multiple vantages in front of the work, Hollowell transfers some of the paintings’ kinesthetic quality to her audience. As we look, we notice ourselves as selves: solid, light, mobile, but nonetheless rooted by gravity. The show’s titular “plumb line,” a weighted cord used to establish a vertical axis, is mirrored in the human spine. Moreover, the mandorla-shaped core of the paintings hangs at a height that matches the average viewer’s torso, as if tethering viewer to work with an invisible umbilical cord. The maternal bodily experience Hollowell’s paintings most directly evoke cannot, by the limits of biology, be universal. But in their phenomenological effects, their demand for an active mode of perception in which see-er and seen merge, the paintings presuppose and reaffirm the individual bodies through which any viewer feels and experiences the world.