- India

- International

Explained: Why soyabean is key to Madhya Pradesh

The crop has often helped shape poll outcomes in Malwa, which accounts for more than half the state’s production. Once thriving, soyabean has suffered falling prices in the last few years.

Soybean has suffered falling prices in the last few years (Express Photo)

Soybean has suffered falling prices in the last few years (Express Photo)

“Malwa is India’s US Midwest and Indore its Chicago. And that’s only because of soyabean.”

There is some truth to this statement by Davish Jain, chairman of the Soyabean Processors Association of India (SOPA). Soyabean in India has an American connection. The leguminous oilseed was hardly grown in the country till the mid-sixties. The first yellow-seeded soyabean varieties were introduced by University of Illinois scientists, who conducted field trials at the Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya (JNKVV) in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh. Many of these varieties — with names such as Bragg, Improved Pelican, Clark 63, Lee and Hardee — were released for direct cultivation. By 1975-76, the all-India area under soyabean had touched around 90,000 hectares.

But the revolution took place only after that — and in Malwa, where soyabean’s relevance, even vis-à-vis shaping electoral outcomes, may be comparable to sugarcane in western Uttar Pradesh.

Where & why

This plateau region of western MP — covering the districts of Dewas, Indore, Dhar, Ujjain, Jhabua, Ratlam, Mandasur, Neemuch, Shajapur and Rajgarh — traditionally grew only a single un-irrigated crop of wheat or chana (chickpea) during the rabi winter season. Farmers mostly kept their lands fallow during the kharif monsoon season. The reason was the monsoon’s unpredictability: Even if the rains arrived on time, it could be followed by long dry spells. Sometimes, it rained so much that the fields would get waterlogged, damaging the standing crop. The best option, then, was to allow the soil to retain water from the monsoon rain and take a rabi crop using this residual moisture.

“The change came with the advent of tube-wells in the mid-seventies. The Malwa plateau is made up of hard basaltic rocks of the Deccan Trap. Since these had aquifers with unutilised groundwater in many places, it was possible to drill tube-wells and grow irrigated wheat. Farmers also now felt no need to conserve rainwater during monsoon. They could, instead, raise a kharif crop on this previously fallow land,” explains P S Vijayshankar of Samaj Pragati Sahayog, a voluntary organisation based at Bagli in Dewas district.

That kharif crop was soyabean, which, unlike urad (black gram) or maize, could tolerate water-logging for 2-3 days and survive dry spells for over three weeks without much yield loss. Also, being a legume, its root nodules harboured atmospheric nitrogen-fixing bacteria. When harvested, it left behind 40-45 kg of nitrogen per hectare — equivalent to nearly two 50-kg urea bags — for the succeeding crop.

Soyabean’s main advantage, though, was duration. The strains imported from US Midwest had a maturity period of 115-120 days from seed to grain. In 1994, JNKVV released an indigenously bred variety, JS 335. It not only matured in just 95-100 days, but yielded 25-30 quintals per hectare, which was 5-10 quintals more. Not surprisingly, this variety very soon went on to occupy around 90 per cent of India’s total soyabean area. The crop duration fell further to 80-90 days with varieties like JS 9560 and JS 2034, developed by the same university.

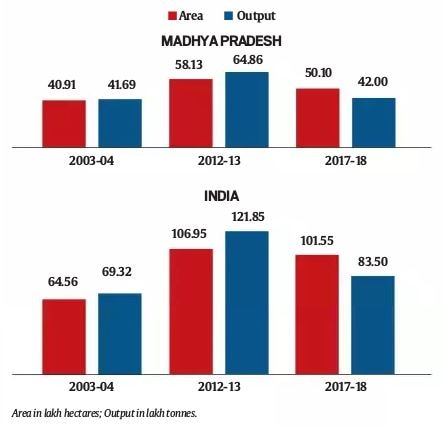

Click image to enlarge.

Click image to enlarge.

The relative hardiness and shorter maturity — at least 10-15 days less than jowar (sorghum) or maize — made soyabean the ideal kharif crop. Farmers could sow it by late-June after the monsoon rains and harvest before mid-October, well in time for planting wheat in November.

“Soyabean was made for Malwa. It could grow well in the region’s black cotton soil and didn’t require much effort; farmers simply had to prepare the field, sow the seeds, do some basic intercultural and weeding operations, and harvest after three months. And they were assured of a minimum yield even under waterlogged or drought conditions,” notes SOPA’s Jain.

By 1979-80, the country’s soyabean area had reached 0.5 million hectares. It rose further to 2.25 mh in 1989-90 and 6 mh towards the end of the century, with MP accounting for 70 per cent. Within MP, soyabean cultivation spread to other districts as well, especially in the neighbouring Vindhya plateau (Sehore, Raisen, Bhopal, Vidisha, Sagar and Guna) and the Narmadapuram division (Harda, Hoshangabad and Betul). But even in 2017, Malwa’s share in MP’s 5 mh (out of India’s 10.2 mh) was well over 50 per cent. Soyabean-wheat became the dominant crop cycle in this region, just as for the US Midwest or paddy-wheat in the case of Punjab and Haryana.

Soyabean’s emergence, however, wouldn’t have been possible without the processors who understood the crop’s true potential. That, in

turn, derived not from sale of its oil domestically. Soyabean had only 18-20 per cent oil content, as against 40-45 per cent in mustard or groundnut. The real money lay in the balance 80-82 per cent de-oiled cake and extractions, also called meal. The protein-rich meal could be exported out, especially to South-East/East Asia where it was used as an ingredient for animal feed. The man to have first spotted an export market for Indian soya-meal, sometime in the mid-seventies, was Kailash Shahra of Ruchi Soya. In no time, other businessmen followed suit, setting up solvent extraction plants for processing soyabean.

Boom & collapse

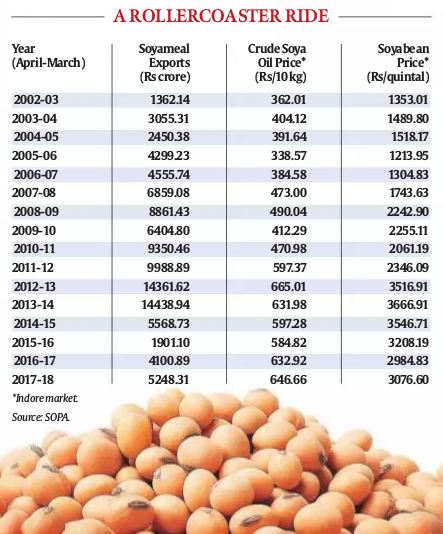

The real boom, however, was to happen only from the mid-2000s, which was when Shivraj Singh Chouhan also took over as MP Chief Minister. Between 2002-03 and 2013-14, the value of soya-meal shipments from India soared from just over Rs 1,360 crore to almost Rs 14,500 crore. As the fortunes of the industry rose — realisations from oil, too, went up — so did that of soyabean growers in Malwa and the neighbouring regions of MP. During this period, the average price of soyabean in Indore market climbed from Rs 1,353 to Rs 3,667 per quintal.

That boom collapsed after 2013-14, along with a crash in global agri-commodity prices. The period since then, coinciding with Chouhan’s third term, has seen soya-meal exports plunge to Rs 1,900 crore in 2015-16, before recovering somewhat in the following years. Soyabean realisations have also fallen to Rs 2,900-3,000 per quintal levels.

“The crisis is not just economic, but also ecological. The soyabean-wheat crop cycle has led to groundwater overexploitation, more so in Malwa. The initial digging of bore-wells was a success, but now you need to dig deeper and deeper, as the top aquifers have been exhausted,” points out Vijayshankar.

Moreover, soyabean itself has over the years become prone to pest and disease attack. “Yellow mosaic virus was once a problem confined to Northwest India. But today, it has come even to soyabean in Central India and we saw it particularly in 2015. There are also fungal diseases such as collar rot, rhizoctonia root rot and pod blight,” says V.S. Bhatia, director of the Indian Institute of Soyabean Research at Indore.

The pests that are increasingly causing crop damage include white fly (carrier of yellow mosaic virus), stem fly (whose larva feeds on the inner part of the stem, making it hollow), girdle beetle and tobacco caterpillar. “The main reason for pest and disease susceptibility is the absence of crop rotation and growing the same variety year after year,” admits Bhatia.

How all these would play out in the current Assembly elections — the ruling BJP had swept the Malwa region in 2013 — remains to be seen. But the role of a crop grown in five mh in MP certainly cannot be ignored.

More Explained

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 19: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05