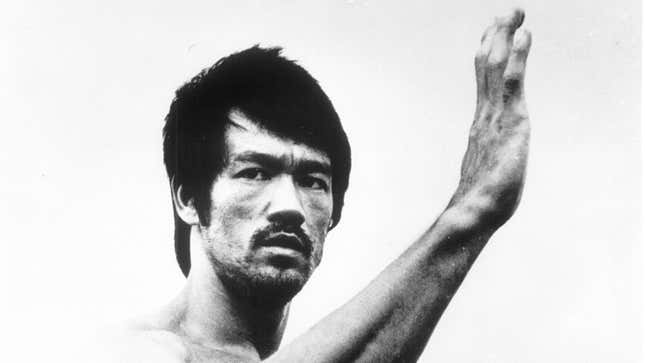

Bao Nguyen’s Be Water is a less traditional entry in ESPN’s 30 For 30 series, centering as it does on Bruce Lee, an actor and martial artist whose grace and athleticism are known the world over, but whose fight record exists primarily in the movies. There’s no denying the impact that the preternaturally charismatic Lee had on martial arts, including giving the world the “style of no style” of Jeet Kune Do, but Be Water occasionally feels more like a biopic than a sports documentary. Nguyen, who explored the legacy of Saturday Night Live in Live From New York!, forms a clear narrative and also takes a more expansive approach to his subject, chronicling as much of Lee’s tragically short life in the 90-minute runtime as possible. As a result, some things, like the Enter The Dragon star’s philosophy and his tutelage under Yip Man, are glossed over, but Be Water still overflows with Lee’s effervescence and Nguyen’s insight.

The documentary begins near the end of the global icon’s life, when he traveled to Hong Kong to begin his collaboration with Golden Harvest and Raymond Chow. This was actually the second “prodigal” return for Lee: He was born in San Francisco in 1940, moved to Hong Kong with his family—led by his father, the actor and Cantonese opera singer Lee Hoi Chuen—as an infant, then was sent to live in Seattle at the age of 18 when he proved a little too keen on fighting. In 1971, Lee, who had been a successful child actor in Hong Kong, was looking to kickstart his career abroad after finding little success in Hollywood: Although he landed the role of Kato on ABC’s The Green Hornet, he had to lobby the writers for more lines, and the show was canceled after one season.

Even when Lee tried to make his own opportunities, such as pitching his own starring vehicle as a kung fu warrior (a premise that reportedly was reimagined as the 1972 series Kung Fu starring David Carradine), he was thwarted by racism both systemic and casual. But Lee’s tenacity and star power weren’t to be denied—he went on to win over international audiences in The Big Boss, Fist Of Fury, The Way Of The Dragon, the unfinished Game Of Death, and the posthumously released Enter The Dragon, the latter of which was a joint Chinese-American production.

These setbacks and milestones will no doubt be familiar to most fans, along with the story of how Lee met his wife, Linda Lee Cadwell, and the revelation about water’s powerful, malleable nature that inspired his own approach to martial arts, which was to reject an attachment to form and rules. Likewise, Nguyen eschews the usual talking head interviews, preferring to let Lee’s family, friends, and collaborators speak over archival footage and photographs, including pictures of Lee fawning over his children, the late Brandon Lee and daughter Shannon Lee (who’s also the president of the Bruce Lee Foundation and an executive producer of Warrior, the Cinemax series inspired by Lee’s writings). Nguyen has said he opted for voiceovers instead of on-camera interviews to keep viewers in the moment, but by the end of the documentary, we can put contemporary faces to the voices of Lee’s friends Leroy Garcia and Jesse Glover, co-stars like Angela Mao and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and his producing partners Andre Morgan and the late Fred Weintraub.

Nguyen also consults with culture critics and authors Sam Ho and Jeff Chang (whose book, We Gon’ Be Alright: Notes On Race And Resegregation, was turned into a series directed by Nguyen), who provide important context. Lee’s life has taken on mythical proportions, which can make it easy to forget what he was up against when he first began auditioning in Los Angeles. Along with Ho, Chang, and Mao, Lee’s brother Robert invokes the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Japanese internment camps—not just the pieces of legislation, but how they were fed by and promulgated anti-Asian racism. Chang describes Lee’s very presence on screen as act of protest, his martial arts prowess symbolizing a controlled fury over what had been done to Asians both in the U.S. and even Hong Kong.

Be Water explores how Lee navigated the different cultures he was born and raised in (his mother was of Chinese and Western European descent), suggesting he learned about Black liberation and the civil rights movement from friends like Glover and Abdul-Jabbar. Before his own legend began to grow, Lee had to contend with the model minority myth that’s only served to drive a wedge between minorities in the U.S. But Lee refused to be played that way; his rejection of rigidity, of strict division, we’re told, also applied to racism.

As the various streams of Nguyen’s storytelling converge, we see just how refreshing his view of Lee’s life is—although there’s plenty of discussion of the obstacles he faced, and of his work to build “bridges” between groups, Be Water never suggests that Lee transcended his race or background. All too often, when a Black person or person of color becomes an international superstar, their success is viewed as almost separate from their race or ethnicity. They succeeded in spite of it; they are embraced by those who insist they “don’t even see color.” But Be Water never forgets Lee’s heritage, or stops celebrating it. Even as Lee is described as “East meets West,” the documentary never stops pondering the ocean between.