The Advantage of a Biden Shadow Cabinet

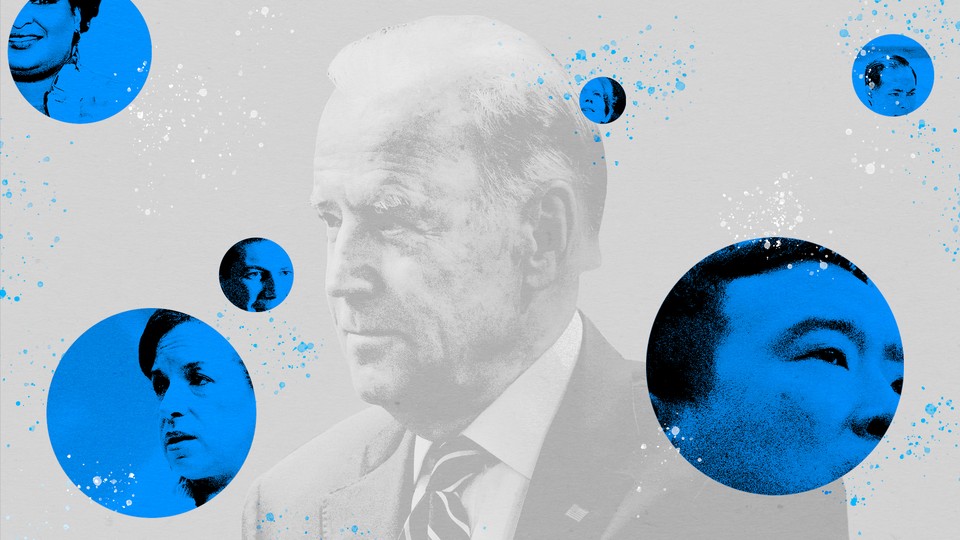

If the former vice president names his future appointees now, it will cast him as the convener of a generational transition in national leadership.

Joe Biden beat a rival in the Democratic primary whose slogan was “Not me, us.” Now a growing number of Democrats believe that Biden should adopt Bernie Sanders’s rallying cry for himself—with a twist.

For Sanders, “Not me, us” conveyed that he viewed himself as the voice and vessel of a mass movement. That’s not a realistic aspiration for Biden, but the slogan could symbolize a compelling alternative role. The “us” wouldn’t be his passionate grassroots following; it would be a new generation of diverse public officials he would promise to bring into government with him if he’s elected.

To run on this message, Biden could identify the officials he would appoint to many of the top Cabinet positions in his administration—a roster that would inevitably include several of his competitors for the 2020 Democratic nomination. That approach would cast Biden less as a singular savior after the bruising conflicts of the Donald Trump years than as the convener of a generational transition in national leadership.

Multiple influential Democrats I spoke with in recent days independently raised the same analogy to describe that possibility: Nodding to the Marvel superhero team, they called it the “Avengers” model for the 2020 campaign. And many of them find that an exhilarating prospect.

“If Biden announced early, ‘Here are the people I’m bringing along that represent different segments of the Democratic Party coalition, different perspectives, people who have brought in policy solutions,’ that would be amazing,” says Aimee Allison, the founder and president of She the People, a national network of women of color. “I actually think it would help a lot of people who were enthused [during the primaries] get reengaged, excited for what’s possible.”

“To the extent he can indicate broadly across the party that a Joe Biden administration will have something for everyone, I think that would be a very savvy move,” says Sean McElwee, a co-founder and the executive director of the liberal polling-and-research group Data for Progress.

Biden himself has nodded to his transitional role, most dramatically at his Detroit rally the night before the Michigan primary in March, which was the last big public event he held before the coronavirus outbreak shut down the country. “I view myself as a bridge, not anything else,” Biden announced at the rally, where he appeared with Senators Cory Booker and Kamala Harris and Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer, all of whom had endorsed him. “There is an entire generation of leaders that you saw standing behind me. They are the future of this country.”

Presidential nominees and campaign strategists have occasionally floated the idea of specifying a Cabinet during an election. But none have done it. Maybe the closest examples are when George W. Bush repeatedly hinted in 2000 that he’d appoint Colin Powell as secretary of state, and when Trump in 2016 released a list of judges he might appoint to the Supreme Court. (That list didn’t include the two men he actually nominated once he was in office, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh.)

The consensus within campaigns has usually been that specifying potential appointees is more trouble than it’s worth. Senior officials from earlier campaigns have said they believed it would be too onerous to vet individuals in the middle of the race. And campaigns have worried that the candidate would be held accountable for everything future appointees say and do before Election Day. For these reasons, they never got to “yes” on the idea.

David Axelrod, the senior strategist for Barack Obama’s 2008 bid, described campaigns’ hesitance this way: “Are you satisfied that they won’t create more problems than they solve?”

When I asked them about the idea, Biden advisers’ initial reaction was similarly skeptical. But both opportunity and necessity might ultimately lead Biden to a different conclusion than his predecessors, some Democrats believe.

The opportunity: Democrats now have a deep bench of younger potential appointees who reflect the country’s increasing diversity. That much was clear in the 2020 primary. Many voters concluded that Harris and Booker, for example, needed more experience before sitting in the biggest chair. But they, among other younger competitors such as Pete Buttigieg, found receptive audiences.

Beyond the 2020 field, Democrats over the past two decades have gained control of the mayors’ offices in most of the nation’s largest cities, nurturing several generations of leaders who have advanced innovative policy on issues including economic development, climate change, affordable housing, and education reform. After their wipeouts in the 2010 and 2014 midterm elections, the Democrats’ recovery in the House, the Senate, and within governors’ mansions also offers Biden an array of intriguing choices.

For Democrats playing the political equivalent of fantasy baseball, it’s not hard to identify a range of potential appointments for Biden—whether he wants to identify individuals for specific jobs or just nod more broadly by indicating several names that would be part of his team in any policy area.

Conversations with Democrats suggest a Biden national-security team, for instance, could include Susan Rice and Tom Donilon, both of whom served as national security adviser to Obama; retired Admiral William McRaven, who organized the raid that killed Osama bin Laden; and Buttigieg, the former South Bend, Indiana, mayor whose experience as a married, gay, religiously devout, polyglot veteran has some Democrats viewing him as the ideal vehicle to represent a changing America to the world as UN ambassador.

A Biden environmental and climate-change team could include Washington Governor Jay Inslee, who set the pace on the climate debate during his own brief bid for the 2020 nomination; former Senator and Secretary of State John Kerry, who might lead U.S. efforts to revive the Paris climate agreement after helping negotiate the original pact; and Mayors Eric Garcetti of Los Angeles and Francis Suarez of Miami, who have pushed for cities to adapt to the growing risk. (Suarez would also advance Biden’s stated goal of appointing Republicans to his government.)

Booker (on job training and America’s workforce), the businessman Andrew Yang (on managing technological change), the former Obama official Julián Castro (on immigration and expanding opportunity in minority communities), and Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms (on housing and urban development) might all fill positions in his domestic-policy team.

Biden’s Justice Department—encompassing those working on racial-equity and voting-rights issues—might include former Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates; Senators Harris, Amy Klobuchar, and Elizabeth Warren; and former Georgia state House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams. (One of them, aside from Yates, could be picked for vice president instead.)

Many on the left would also thrill to see Warren as treasury secretary, though that would send shockwaves through the party’s Wall Street supporters. Easier to imagine is Biden turning to the Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates to help lead the government’s response to the coronavirus and plan for potential future epidemics.

If the talent among younger Democrats represents the opportunity in this approach, the necessity is this: Public polling consistently suggests that Biden, a 77-year-old white man first elected to office in 1970, won’t ever inspire an eruption of enthusiasm among the activist liberals and young voters who were drawn to Sanders, or among younger people of color more broadly.

Stephanie Valencia, a co-founder and the president of EquisLabs, a Democratic firm focusing on Latino voters, recently completed a poll in 11 battleground states that found one-third of younger Latino men and two-fifths of younger Latinas were at best ambivalent about supporting Biden. “He is obviously who he is,” she told me. “There was a magnetism factor to Bernie Sanders, and so he can’t recreate that.”

Like Allison, Valencia raised the “Avengers” analogy to argue that identifying appointees could stir voters unenthusiastic about Biden himself. “I think they have to look for every opportunity to give people something to be excited about,” she said. “Showing the ‘Avengers team’ … I think can give people a lot of hope about the possibility of government.”

Nominees often rely on their vice president to send a welcoming signal to elements of their party skeptical about them. There’s no guarantee Biden will pick a ticket-balancing VP: His emphasis on loyalty and personal comfort with his running mate might lead him, for example, to Klobuchar, who comes from the same center-left wing of the party as he does.

But even if Biden picks a running mate who offers more balance, no single person could satisfy all the demands on him. Warren would thrill liberals but disappoint those seeking a woman of color. Harris would cross that bar but disappoint liberals. Abrams might satisfy liberals and advocates of diversity, but with such limited government experience, she seems well short of meeting Biden’s own standard of a candidate ready to assume the presidency on day one. “He can’t check all the boxes in one human being,” says Jeff Weaver, a former senior adviser to Sanders.

The principal benefit of naming a potential Cabinet now is that it offers Biden much more than just that one box in which to signal inclusion. For that reason, Sanders’s campaign was seriously considering identifying a Cabinet before the election if he had won the nomination, Weaver told me. “You then have different people who can speak to different parts of your coalition with credibility, and parts of your coalition can see themselves reflected in your administration,” he said.

Weaver likened the idea to the “Shadow Cabinets” that opposition parties identify in parliamentary countries, such as the United Kingdom. Both he and Allison described this approach as producing a “force multiplier” for the nominee, because supporters tagged as future appointees would likely attract far more media attention than a conventional surrogate would. That’s the flip side of the concern about candidates being responsible for a potential appointee’s words: Those words would resonate more powerfully. Weaver said the benefits for Biden would be obvious, “if you could have nine or 10 people on the stump not just as surrogates but as prospective members of the administration.”

It would compound the effect, he continued, if “occasionally you bring them together on a stage where you can see the full diversity of the administration in every sense on display.”

In fact, although Biden’s primary-campaign events were often sleepy, arguably his most compelling appearances came in the 48 hours before Super Tuesday, when he appeared in Dallas with Buttigieg and Klobuchar, and then in Detroit with Whitmer, Harris, and Booker. Ceding more of the spotlight to those rising figures didn’t so much marginalize as energize Biden. The events cast him in a role that seemed very natural: the unifying conductor of a broad transformation, not the solitary visionary who will transform the nation by his singular force of will.

There’s something of a legal question about whether a nominee can name a Cabinet before he’s elected. The 1925 Federal Corrupt Practices Act, as adjusted during the Watergate era, imposes penalties on anyone who “promises or pledges the appointment … of any person to any public or private position or employment, for the purpose of procuring support in his candidacy.” But many legal scholars think that final “procuring support” clause offers an escape hatch: A nominee can say he’s promising to appoint people who already support him, not trading jobs for votes. Identifying potential appointees as the members of a team, rather than promising them a specific job, would further diminish the risk of crossing that statute.

Naming a potential Cabinet this summer could offer Biden two other advantages, the idea’s supporters believe. One is that it would send a clear message that he’s ready to start working immediately to confront an extremely precarious economic and public-health landscape. It would also starkly contrast his potential administration with a Trump government dominated in almost all key positions by white men.

Apart from his decision to support gay marriage before Obama did, Biden over his nearly five decades in Washington has rarely taken big risks. And there are understandable reasons why every earlier nominee who considered identifying a Cabinet ultimately decided not to do so. But against those traditional calculations is the powerful prospect of a final night at the Democratic convention when Biden could stand at the center of a stage (whether in person or virtually) with Warren, Harris, Klobuchar, Abrams, Buttigieg, Booker, Castro, McRaven, Rice, Garcetti, Bottoms, Yang, Gates, or others and declare that “not just me, but all of us” are coming to reset the nation’s direction.

“I think our understanding of what’s risky in this moment has to change. The most risky thing is status-quo, business-as-usual politics when Trump is in the White House and our economy and health are being ravaged by the pandemic,” Allison said. “The risk is to pretend, to whistle in the dark, to say, ‘We’ve done this so many cycles; we know how to do this.’ No, you don’t. If there is anything that this time is calling for, it’s to go boldly and resolutely toward knitting together the coalition to win and be prepared to govern and help bring this country back to some kind of normalcy.”

In other words: Avengers, assemble?