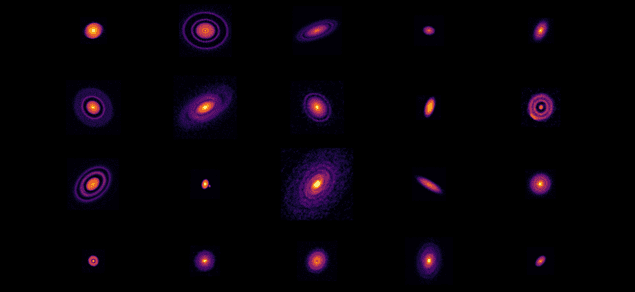

“Stunning” high-resolution images of 20 nearby protoplanetary discs have given astronomers a wealth of new information about how planets form around stars. Taken by the ALMA radio-telescope array in Chile, the images reveal that gas-giant planets ranging in size from Neptune to Saturn can form much faster than previously thought. A comprehensive study of the images also suggests that gas giants can be created much further from their host stars than had been expected. The observations also provide important clues about how Earth-like rocky planets are created.

Over the past three decades, astronomers have catalogued nearly 4000 planets orbiting stars other than the Sun. These extra-solar planets – or exoplanets – include exotic objects such as “hot Jupiters” and “super Earths” and astronomers now know that exoplanetary systems exist in myriad forms – with some being very different to our familiar solar system.

While astronomers have yet to observe an exoplanet that is truly Earth-like, studying how exoplanetary systems form and evolve could provide important clues about how the Earth itself came into being. Armed with this knowledge, astronomers could work-out how many Earth-like exoplanets should be lurking nearby in the Milky Way.

Sticky dust

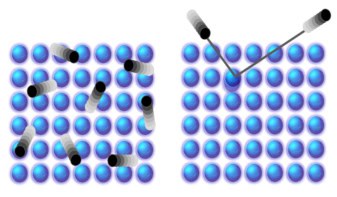

Systems of planets form from protoplanetary discs of gas and dust that surround young stars. The conventional model says that this process occurs slowly over many millions of years and in a hierarchical manner – with dust particles colliding and sticking together to create larger objects that then collide and stick together.

The ALMA survey was done by the DSHARP collaboration and was led by Sean Andrews at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center Astrophysics; Andrea Isella of Rice University; Laura Pérez of the University of Chile; and Cornelis Dullemond of Heidelberg University. Light from the host stars interacts with dust, causing it to glow with radio emissions. The team made systematic comparisons of the structures of 20 discs and were able to discern features as small as several astronomical units (1 AU is the distance between the Earth and Sun) in some of the discs.

Unseen planets

The team found that some structures such as concentric gaps and narrow rings are present in nearly all of the discs. Spiral and arc-like features were also spotted in some of the discs. They believe that some small-scale features are created by unseen gas-giant planets, and their existence in relatively young protoplanetary discs – some just one million years old – suggests that gas giants form much faster than previously thought.

“The most compelling interpretation of these highly diverse, small-scale features is that there are unseen planets interacting with the disc material,” explains Andrews.

ALMA debuts its high-resolution results

Some of these features are very distant from the host stars, with the furthest being more than 100 AU away – about three times the distance between Neptune and the Sun. This suggests that some gas giants form in very large orbits, which was not expected before astronomers began observing protoplanetary discs.

The astronomers believe that protoplanetary disc structures could hold the answer to reconciling an apparent flaw in the hierarchical model of planet formation. In a smooth disc, once an object reaches about 1 km in diameter it is prone to being sucked into the star. This is not necessarily the case once the disc has become structured, and this could explain how rocky planets like Earth could form relatively close to stars. Planetary formation should also proceed more rapidly within a ring – where dust density is high — thus accelerating the planet-formation process.

The research is described in ten papers that have been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.