The utilitarian title of Queens Remy Banks’ new “did this in detroit.” EP serves to tell the listener something that might go under the radar if they were going by the lyrics alone. He recorded in the Motor City with producer Black Noi$e. But even though Banks camped out in Detroit rapper Danny Brown’s Bruiser House studio for the entire recording of the EP, he couldn’t seem to get Queens off of his mind.

“Hailing from the World’s Borough / I be global when I rep it / you see love and spread it / just hope to get the message / it’s cut from a different cloth / speak with a different texture,” Banks raps on the second track of the album that focuses on his home neighborhood.

The way Banks tells it, when he was growing up in Queens in the 1990s, rap was practically in the water. But while his childhood may have inculcated an encyclopedic knowledge of genre in him, it was the internet that gave him his start. Banks said that it was his long distance connections to rappers and producers like Domo Genesis of Los Angeles’ Odd Future crew and Black Noi$e of Detroit’s Bruiser Brigade that ended up helping to fuel his early career.

Banks recently talked to QNS about the tightrope between regionalism and internet culture, the formation of his Queens-based rap crew World’s Fair, his memories about growing up in Forest Park and the process of recording his new EP. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

QNS: You really rep Queens. You talk a lot about it in your music. Obviously this borough has been home to some of the most classic rap albums of all time, but it seems like nowadays in rap, it’s not as common to rep your home city. I’m wondering why you think that is.

Remy Banks: I think things became less regional in rap because of the internet. It’s like the internet influence made it easy for people to access different things that they didn’t see in their home state or their home city or on the block. Like they were getting exposed to the Southern slang or like my little brother, he’d be running around saying, “Yo, you cappin’ bro.” And that’s like an Atlanta thing. I’m laughing like that’s crazy. Slang from Atlanta was not coming out of my mind when I was his age. So the influence made things less regional.

QNS: So how do you think that everyday experience of living in a city influences your writing process and what you rap about?

RB: I write about what I’m going through in my daily life. Whatever I’m feeling that day, I’ll write that down. If I’m home or if I’m in the city, I’m writing about what’s going on — family stuff, the community, different culture, different subcultures, different parties — all of that is happening in my music because it’s happening around me.

QNS: What were you up to when you were in Detroit? What was your favorite thing to do there?

RB: Well, my favorite thing to do is just wake up, stretch, do some pushups, brush my teeth, roll up, smoke, wait for [producer] Black [Noi$e] to wake up, try to figure out what Zelooperz is up to because like I was staying in a Bruiser house, which is like this big a– house that Danny [Brown] brought. It’s got two studios in there. So, I’m just around music all the time. When Black’s awake, he’s chopping a record up or he’s playing beats that he just made in his room the night before. So I’m just like hearing stuff from the room I’m in and I’ll just walk over to the studio and just start writing. So whatever beat that was going on and however it made me feel, I would just write it down.

QNS: When I was growing up in the suburbs of Connecticut, New York City rap was basically like a monolith to me. There was East Coast, West Coast and the South and I kind of thought of them each as cohesive things. Now that doesn’t seem as accurate to me. What are your opinions on what separates Queens rap from other subgenres of New York City rap?

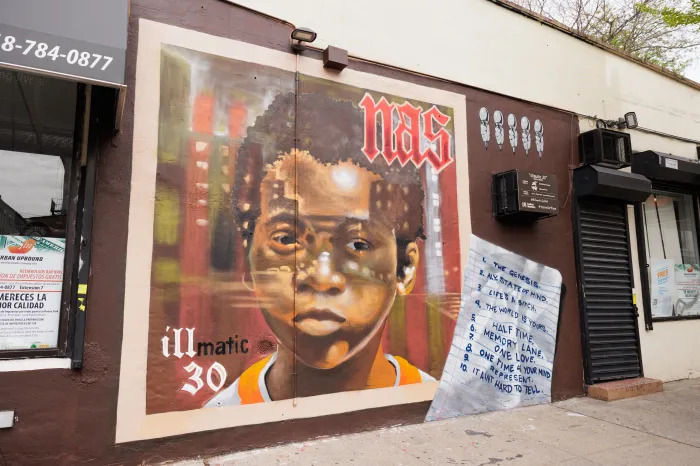

RB: Yeah, when you go back in time, I feel like New York had different pieces to the puzzle. Brooklyn had like a very raw energy, like in-your-face-energy. But then you also had groups like Black Moon. Buckshot had this very smooth demeanor. And then you had groups like M.O.P. that were very rambunctious, very animated, which was also very dope. And then you had like your Harlem rap like Cam’ron. Cam was ill. Big L was very lyrical. Then you had Queens like you had Tribe Called Quest, you had Nas. They painted very vivid pictures with their rap. They painted landscapes and I feel like that’s still the way it is today.

QNS: How did growing up there impact your appreciation of the art form?

RB: I was around it growing up. Like when Nas was coming up, I was a little kid listening to him because of like my older cousin, my stepfather, my mother and the radio. Same thing with Jay-Z. Same thing with Biggie [Smalls]. There was a lot more New York artists on the radio back then, let’s put it that way. So as a kid growing up in the city, I was exposed to everything that was happening in every borough because every artist that was popping from any borough was being played on Hot 97. So it was dope. It was a beautiful time. And I feel like that helped mold me. Growing up in the city at that time you were conditioned. You went to the Bronx Zoo. You went Coney Island as a kid. You went to Central Park as a kid. I was exposed to the city from a very young age. I was already adapted or conditioned to being in different parts.

QNS: I read that you grew up in Jamaica.

RB: I was born in Booths Memorial, which is in Flushing. And then I lived on 88th Avenue between 149th and 150th street in Jamaica. I lived there until I was about 4. Then I moved to New Jersey for a year for kindergarten. Then we moved them right back to the same block in Jamaica. And then we moved from there to LeFrak and then from LeFrak to Forest Hills, and I’ve been there ever since.

QNS: At what age did you start making like connections and inroads to rap scenes in Queens?

RB: Well there wasn’t really any rap in Queens. That’s why I feel like World’s Fair is definitely important to the borough because after a Tribe Called Quest, and G unit — after Lost Boyz, Queens was very quiet — at least on the forefront of things. When we started to come up, it was a resurgence because of independent kids. With us putting up our own music on YouTube or Mediafire. In our era, there were no groups in Queens, so World’s Fair was that.

QNS: Are there other Queens artists you want to shout out?

I love Dean Spencer. Duendita. Shout out to Jef Donna from World’s Fair who just dropped a new song today. [Action] Bronson. Money Magic. Shoutout to the southside.