On Friday, the North Carolina Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling that grants more than 130 death row inmates the opportunity to have their sentences reduced if they can prove systemic racism affected their sentencing.

The ruling stems from a controversy over a 2009 law called the Racial Justice Act, which allowed death row inmates in North Carolina to appeal their sentences, and potentially have them reduced, if they could provide statistical evidence that the death penalty as carried out in the state or county was inherently racially biased at the time of their sentence. That law was amended in 2012 and then overturned in 2013 by the conservative state Legislature, blocking more than 130 North Carolina death row inmates from seeking relief.

On Friday, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the repeal and key elements of the amended law were unlawful ex post facto changes under both the U.S. and North Carolina constitutions. Critically, because the court cited the state constitution and its own prior case law in reaching its conclusion, the decision cannot be overturned by a federal court.

“Here the right is to challenge a sentence of death on the grounds that it was obtained in a proceeding tainted by racial discrimination, and, if successful, to receive a sentence of life without parole,” Justice Anita Earls wrote. “Repealing the RJA took away that right, and the repeal cannot be applied retroactively consistent with this state’s constitutional prohibition on ex post facto laws.” In reaching the decision, Earls cited a more than 158-year-old North Carolina Supreme Court ruling against ex post facto laws that protected Confederate soldiers who may have committed crimes in uniform, after an amnesty law was revoked. Ironically, the standard that protected Confederate soldiers will now be applied to black people on death row.

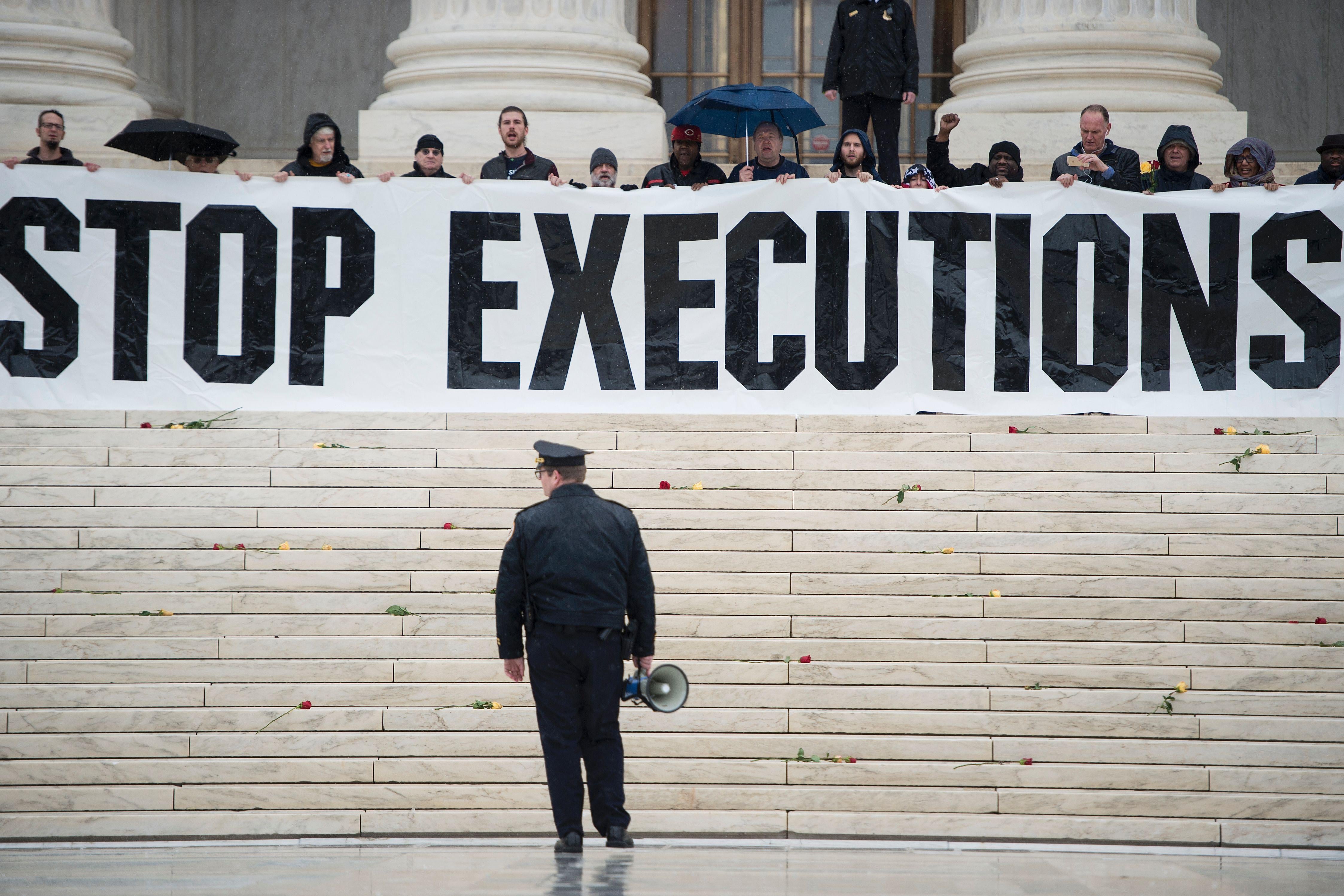

The ruling was also an enormous victory for death penalty opponents. “I think that the timing of this opinion is really powerful,” said Cassandra Stubbs, the director of the ACLU’s Capital Punishment Project and one of the litigants in the case. Stubbs notes that the opinion comes during a week in which Chief Justice Cheri Beasley, the first black woman to serve as chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, issued a powerful public call for racial justice in response to the murder of George Floyd.

In a speech on Tueday, Beasley nearly broke into tears describing how urgent the calls for racial justice are for her personally, “as the mother of twin sons that are young black men.” Critically, she called for a reasonable, compassionate, and immediate response to protesters by the legal system, even when some break the rules:

These protests are a resounding, national chorus of voices whose lived experiences reinforce the notion that black people are ostracized, cast out, and dehumanized. Communities are crying out for justice and demanding real, meaningful change. It is shocking to see our workplaces, businesses, and community spaces damaged, but we must recognize the legitimate pain and weight of years of disparate treatment that fuels these demonstrations. We must be willing to hear that message, even when we are saddened by the way it is delivered. We must decry the failures of justice and equity, just as forcefully as we decry violence. It is not enough to say to protesters, go home and follow the rules. It’s just not that simple.

Now Beasley’s court has issued an opinion that lays the groundwork for men and women on death row who may have been sentenced under a racially biased system to have their sentences reduced to life in prison. For anyone who filed an appeal before the RJA was revoked by the Legislature, the law allows death row prisoners to attempt to prove that systemic racial bias tainted their sentences, by pointing to simple evidence of disparate treatment either in the exercise of peremptory challenges to potential jurors or in how the death penalty has been implemented in a particular jurisdiction.

In keeping with findings from elsewhere across the country, the evidence in the limited number of RJA cases that previously made it to the hearing stage demonstrated, unsurprisingly, that there was racial bias in the implementation of the death penalty in North Carolina, and that it was even worse in specific counties.

As I wrote last year about the cases:

A study conducted by Michigan State University College of Law found that in 173 death penalty cases between 1990 and 2010, prosecutors in North Carolina were about 2.5 times more likely to strike black jurors from the jury. In Cumberland County, cases with white victims were more than 3.4 times as likely to result in the death penalty than those with victims of another race.

Now the prisoners covered by the decision will be able to point to these concrete numbers and raise a challenge to their own individual death sentences.

“The big looming question is going to be how North Carolina courts deal with this evidence,” notes Stubbs.

In her stirring call for a reckoning with racial injustice earlier in the week, Beasley may have sent a signal to lower court judges in her state as to the approach she will take to these cases.

“As Chief Justice, it is my responsibility to take ownership of the way our courts administer justice and acknowledge that we must do better,” she said. “We must be better.”

Correction, June 6, 10:15 p.m.: This article originally misattributed the authorship of the opinion in this case to Chief Justice Cheri Beasley.