Some N.J. districts pile up debt building schools, others are debt-free

Although New Jersey is in better shape than the country as a whole for school debt, paying off construction bonds costs about a quarter of state’s annual debt service.

(bobelias/BigStock)

This story originally appeared on NJ Spotlight.

—

New Jersey provides several ways to help school districts fund construction projects, but that hasn’t stopped some districts from amassing huge amounts of debt as they construct state-of-the-art facilities, sometimes for relatively small numbers of students.

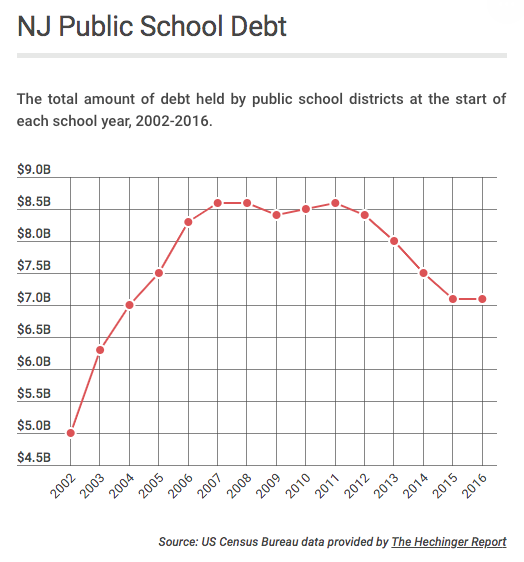

In total, New Jersey public school districts ended the 2016 school year $6.9 billion in debt, according to an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data provided by The Hechinger Report as part of its Districts in Debt series. That amounts to about $5,100 per student. While that sounds like a lot, New Jersey is in better shape than the nation as a whole. School debt in the United States totaled $434 billion in 2016 — the latest year for which complete numbers are available — which averages out to about $8,900 per student, Hechinger reports.

Still, the data shows 113 New Jersey school districts started the 2016 school year with more than $10,000 in debt per pupil and 23 had more than $20,000 in debt per pupil. One district, Cumberland County Vocational, had amassed close to $150,000 in debt per pupil as a result of the construction of a new $70 million building in Vineland. On the other hand, the data shows that 97 districts had no outstanding debt in 2016.

While the average district’s debt load may be comparatively low, the state has taken on the burden of so much school construction that the amount it spends each year paying off the bonds used to finance the buildings — about $1 billion — equals about a quarter of the state’s total debt service.

Three ways the state pays

New Jersey helps ease districts’ debt burdens in one of three ways:

- The Schools Development Authority pays the full cost of the construction of buildings in 31 needy districts known as Abbotts because they were part of the Supreme Court’s Abbott v. Burke school-funding decisions. A May 1998 decision, affirmed two years later, requires the state to foot the bill for school construction in these districts. The state Economic Development Authority issues bonds for the SDA to pay for the cost of new buildings and emergency repairs in the Abbott districts. New buildings follow model designs and the SDA oversees the work. There is almost no money left for these projects.

- The SDA makes grants available to the rest of the state’s districts to help pay for their construction when needed to address health and safety issues, ease overcrowding, provide space for disabled students or accommodate full-day kindergarten where that is required. Districts can get up to 40 percent of their costs covered. Currently, there are no more funds available for these grants, however.

- The state Department of Education provides debt-service aid to districts that don’t get construction assistance, provided their projects comply with the DOE’s facilities efficiency standards and are used for instruction — not solely for administrative or athletic purposes. The amount is based on a district’s wealth, with most districts getting 40 percent of the cost of the debt repayment, said Michael Yaple, a DOE spokesman. Others, though, said the state does not often fully fund debt service. Current language in the state budget gives districts just 85 percent of their debt-service allotment, which has reduced that 40 percent closer to 34 percent of the cost.

Gov. Phil Murphy has proposed giving about $128 million to 282 school districts for debt-service aid next year, roughly 2 percent less than in the 2018 fiscal year.

Since 2000, the state Legislature has approved $12.5 billion in funding for school facilities projects — $8.9 billion for Abbott districts, $3.5 billion for grants to other districts and $150 million for vocational schools, according to the authority. Through last September, the SDA and its predecessor had issued $10.8 billion in bonds.

EXAMINE NEW JERSEY PUBLIC SCHOOL DEBT BY DISTRICT

Many schools need a lot more work

“Full funding for the poorest districts has ensured that many of them have adequate facilities,” said Bruce Baker, a professor in the Graduate School of Education at Rutgers University whose research focuses on the adequacy and equity of state-aid allocations. Still, he said there are “many examples” of schools needing substantial work that have not been funded yet.

Overall, state policies have meant New Jersey school districts have not had the types of problems paying off their debt that some districts elsewhere in the nation have.

“School districts are very sensitive about monitoring their debt service,” said John F. Donahue, executive director of the New Jersey Association of School Business Officials. “As debt rolls off the books, districts can consider needed capital projects with minimal local tax impact.”

Frank Belluscio, deputy executive director of the New Jersey School Boards Association, said that while they were still available, the SDA grants to regular operating districts “were extremely helpful to school districts in meeting facility needs by reducing the amount of borrowing necessary and the cost to taxpayers.”

But while SDA funds have lessened the burden on local taxpayers to pay for construction, it has spread out that cost among all New Jerseyans. The state expects to spend more than $1 billion a year on debt service for those bonds from now through the 2023 fiscal year, according to the State of New Jersey Debt Report Fiscal Year 2017. Some of those bonds do not mature until 2040. The debt service for public school construction amounts to one-quarter or more of the state’s total debt service for those years.

Pricey projects

According to the state budget proposal for FY2020, the DOE approved about 1,200 long-range facilities projects to meet schools’ current and future needs in the 2018 and 2019 fiscal years. It expects to OK the same number next year.

School building projects have gotten pricey, with some recent high-profile construction in the state costing more than $350 per square foot.

The Cumberland County Technical Education Center’s $70 million price-tag bought a 200,000-square-foot buildingwith 78 instructional areas on about 52 acres, according to the project description posted on the website of the Cumberland County Improvement Authority, which handled the project. It includes areas for engineering, health sciences, studio production, automotive technology and culinary arts, as well as a gymnasium and library. Transitioning from a small part-time program to a full-time one, the school currently has 552 students, but expects to eventually enroll about 1,000.

Hudson County’s new High Tech High School, which is expected to serve twice that number, had a design and construction budget of $150 million. Opened last September, the 350,000-square-foot school on 20 acres in Secaucus includes a fabrication lab, a theater and a TV production studio, as well as a dance rehearsal space, labs for environmental and biomedical studies and a fully-equipped gym. The acting superintendent of the Hudson County Schools of Technology, Amy Lin-Rodriguez, was quoted by RE-NJ.com as saying, “The Frank J. Gargiulo Campus will quickly become the gold standard for technical high schools across the country.”

Technical schools are expensive because they need special spaces and equipment that a typical school does not. Paying off these schools’ construction costs also falls on a larger population — an entire county, rather than a single community. Those payers don’t, however, get a direct say in approving the construction because these projects are not subject to referenda. County officials make that decision. The state also provides more debt service — up to 90 percent — to vocational districts that serve a lot of students from Abbott districts. Cumberland Tec serves three Abbotts — Bridgeton, Millville and Vineland. Hudson’s vocational district serves five: Harrison, Hoboken, Jersey City, Union City and West New York.

When the SDA foots the bill

A local vote is also not needed for projects undertaken by the SDA since the state is footing the bill. The authority announced earlier this month its largest single procurement yet: a new high school for Perth Amboy whose cost is estimated at between $210 million and $230 million. The three-story building is to provide 576,000 square feet for about 2,800 students.

“The new Perth Amboy High School project will help to address the significant overcrowding that exists in the Perth Amboy School District and will provide students with access to a modern facility that will help them to reach for success,” SDA CEO Lizette Delgado-Polanco said in a statement.

It also can be hard to get New Jersey voters, many of whom already feel overtaxed, to support a construction project. Districts wishing to borrow money to make major repairs or build have to ask for voter approval via a ballot question. These are not always successful.

“Approval obviously depends on the community and the local tax impact,” Donahue said. “Security and early childhood projects enjoy the most support.”

Voters don’t always go along with proposals

Baker noted that not all voters are interested in investing in public schools or may not be able to afford the additional cost that comes with building a new school. His research has found significant benefits when children attend class in schools with high-quality lighting, properly functioning heating and cooling systems, clean air and water and with access to safe outdoor play spaces. Children’s rights to good schools should not be subject to the whims of voters, Baker said.

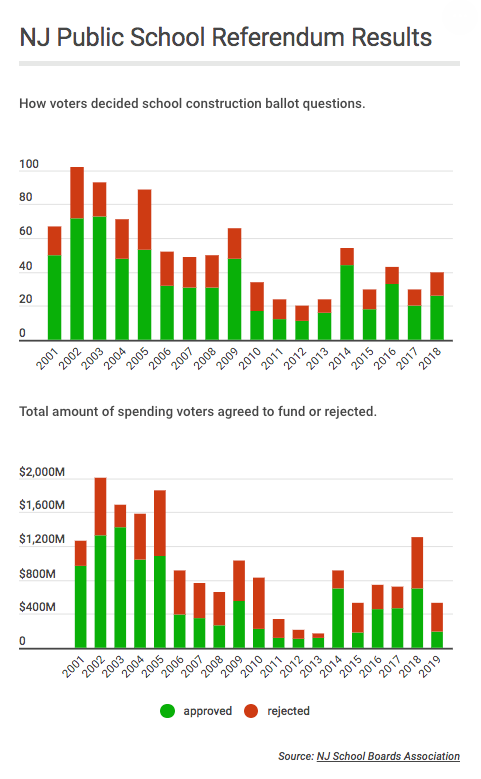

An analysis of NJSBA data shows that voters have approved about two-thirds of all construction spending placed before them since 2001. They are more likely to endorse lower-cost projects, voting to spend just 59 cents of every $1 that district officials have requested.

“Even with the offset provided by state funding, school districts must still gain voter support for construction projects,” Belluscio noted.

Even in districts with higher than average incomes and little poverty, voters can reject ballot questions.

In Cherry Hill, voters last December balked at spending as much as $210 million on construction. The district had put the work on the ballot as three separate questions, with passage of one measure required for approval of the second and third. All three failed. The first request, for $49.7 million, sought to make security upgrades at 15 schools, fully or partially replace the roofs on a dozen buildings, make infrastructure repairs at all but one school and add a new multi-purpose room to one elementary school. The second and third questions would have paid for other upgrades, renovations and expansions district wide.

State law sets limits on how much money schools can borrow, a maximum of 4 percent of equalized property values in the community or communities comprising the district for virtually all districts in the state.

Fewer districts have added debt recently

The total debt owed by New Jersey school districts has increased by a somewhat higher rate than enrollment has risen since 2002. Adjusted for inflation, the $7.1 billion debt at the start of the 2015-2016 school year was 6 percent higher than the 2002 inflation-adjusted debt load of $6.7 billion. During the same time, total enrollment rose by little more than 2 percent, with close to 1.4 million students. More districts held debt — 473 in 2016, compared with 447 in 2002.

But fewer districts have added debt in more recent years. More than 110 districts a year bonded for school construction or repairs in the early 2000s, compared with fewer than 50 a year in 2015 and 2016. The larger number in the early 2000s was due, in part, to the popularity of the provision of the Educational Facilities Construction and Financing Act of 2000 that committed the state to pay $4 of every $10 of debt service.

“Many districts took advantage of this opportunity,” states an article by Robbi S. Acampora in the NJSBA’s May/June 2018 School Leader publication. “For New Jersey districts the timing could not have been better. Some of these districts were lagging in updating their buildings while others were experiencing increased enrollment and needed new buildings. The opportunity to take advantage of 40 percent funding was too good to resist. Some districts built new schools every few years. The total amount of bonds issued was unprecedented.”

Some districts may be delaying construction today because money for the grants to non-Abbott districts has run out.

With much debt being retired, school districts have an opportunity to do additional construction work that might be needed. Acampora wrote that many of the districts that issued construction-related bonds between 1997 and 2006 will be debt-free within the next few years and districts with facilities needs that prepare new building plans to coincide with the retirement of old debt can do work without increasing taxes, provided the cost is not much larger than the cost of the prior project.

Voters in Cherry Hill said ‘no’

“Many districts have debt service coming ‘off the books’ in the next few years and using that allocation can allow new projects to be financed with little or no tax impact,” Acampora wrote.

But Cherry Hill found out that does not always matter. According to the district, approval of all three questions would have brought an average tax increase of $307, but because $75 was coming off the tax rolls due to the retirement of existing debt, the net increase would have totaled $232. Given the end of that debt payment, the first construction proposal would have left the average Cherry Hill homeowner saving $4 a year in property taxes yet voters rejected it. The district paid off the last of its debt from a 1999 bond, said Barbara Wilson, a district spokeswoman.

The district, which was not getting an SDA grant, decided to re-examine its proposal and its goals and try again for a new project, probably in the fall of 2020.

The size of district building needs in the state is unclear. Each district has to file a long-term facilities plan with the DOE but there has been no overall assessment of the condition of New Jersey’s schools. Sources have estimated the Abbott districts alone need another $4 billion in construction work and it is unlikely lawmakers would approve that much additional bonding without providing more money in grants to non-Abbott districts, as well.

How future construction will be funded and managed is also unclear. With the patronage scandal currently engulfing the SDA, state Sen. President Steve Sweeney (D-Gloucester) has said he does not want to give the authority more money to oversee but would rather see the EDA handling school construction matters.

System in NJ ‘generally works well’

Donahue said the state’s three-tiered system of paying for all or part of school construction costs “generally works well,” but would be better if the state met its statutory obligation to pay 40 percent of debt-service costs.

He would support the elimination of the SDA, saying that both Abbott and regular operating districts “have the ability and expertise to manage their capital projects without the burdensome oversight that has been in place by way of the Schools Development Authority.”

New Jersey’s current system has worked relatively well for the Abbott districts for which the state builds schools and the wealthiest districts that typically can afford and get voter support for construction, Baker said. But that’s not necessarily the case for other poorer and middle-class districts.

“NJ has taken a better approach than most states,” he said. “But it’s not a smooth scale from the poorest to wealthiest … Rural, middle class and lower income districts (other than those at the bottom) have felt the squeeze in New Jersey … This is why state aid is really important for ensuring equitable access to adequate school facilities.”

There are two ways to look at district debt. NJ Spotlight has created a searchable database using recent census data provided by Hechinger. Additionally, the Hechinger Report has created a tool that allows a reader to see a district’s debt and revenues over time and compare that to state and national averages.

—

This story is part of the series Districts in Debt, which examines the hidden financial pressures challenging American schools. The series was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.