An angel of Austin, music teacher lifts kids amid town's drug recovery

This is the first of a four-part series on Austin, Indiana, the home to the worst-ever drug-fueled HIV outbreak in the nation.

AUSTIN, Ind. – Kasey Brandenburg crouches in the dewy grass near her mother’s grave, dusting every crevice of an angel figurine with her fingers. She gently places it at the base of a sunlit stone etched with musical notes, a guitar and lyrics of a favorite song.

Every time she visits, she remembers she was born into music — her mother an angel-voiced singer and her father a drummer named Elvis.

But addiction killed both by the time Kasey was 10.

And she knows, touching the cold granite, that the music inside her could have died along with them if not for those who stepped in to keep it alive.

People like Kathy Risk-Sego.

The Austin High School music teacher helped give Kasey a voice and taught her to sing.

Kathy does that for all her kids.

She directs the show choir at Austin High School, where many kids endure serious hardship along with the usual trials of growing up. Addiction, poverty and despair have long festered in this former farming village 37 miles from Louisville.

Once a picture of the country’s heartland, Austin in 2015 became the epicenter of the worst HIV outbreak caused by IV drug use in rural America. Shame deepened and lingered.

Austin Rising: Explore our coverage of a devastated town that found hope

At its height in 2015, the state transportation department briefly put up a lighted sign geared toward truckers at the rest stop nearest to Austin, saying: "WARNING HIV OUTBREAK."

But like music that can’t be silenced, hope is rising.

Lifted by young voices, it is strong.

Kathy is one of Austin's many angels, people sowing that hope through education, faith and a commitment to recovery.

They are the people behind Austin's rise, the ones who together heal the community, nurture compassion, and safeguard the future by caring for Austin's children. They're fighting despair, and the town's drug problems, with love and determination.

And they're winning.

Kathy is on a mission to nurture young voices at the impressionable cusp of adulthood. She’s a role model who gives hugs, direction and dreams. She applies, in equal measures, silliness, discipline and tenderness. Her husband calls her “a wellspring of hope.”

The kids just call her “mom.”

Her choir is a refuge and a family.

One of every four kids in Scott County lives in poverty; six in 10 get free or reduced-price lunch.

But at Austin High School, graduation rates have climbed steadily since 2014 and now exceed 90 percent.

In its show choir, Dimensions, which has a budget of about $25,000, students compete against rivals with behemoth budgets, some in the hundreds of thousands of dollars — and sometimes beat them.

Kathy's kids see, some for the first time, the world beyond Austin. They see what's possible.

“I often think of how I would change this town if I really could, and it’s like just having a lot more places where you could go and escape rather than (do) drugs," 19-year-old Kasey says. "Because that’s all people are doing — they want to escape everyday life, everyday tragedy and struggle.

Related: Austin man builds new life after addiction recovery and HIV treatment

"It’s really hard when everyone’s in poverty and they don’t know what to do and don’t know where to go, so they resort to what their family’s done. It would be so easy for me to say, ‘My family did drugs, so I’m going to do drugs.’ But I’m going to break that chain.”

After graduating from high school, Kasey wrote Kathy and her husband a thank you note that still hangs in the show choir office.

(Kathy,) you kept the fire within me burning and you never let me give up. For that I am forever grateful. ... I love you with every fiber of my being. I will make you proud!

Just outside that office, other choir kids gather for class — 28 of them, all full of potential.

Kathy gathers them around her piano. A tiny, blonde 46-year-old brimming with energy, she looks up over her sheet music and glasses. She teaches them lyrics to the Fireflight song "Now."

They are words she hopes they take to heart:

You’re not hopeless

You’re not worthless,

No

You are loved.

A musical mission

Kathy felt that God called her to Austin. He pointed her toward her mission even as a child.

She grew up about 30 minutes away, on the rural outskirts of Madison, the daughter of a teacher’s aide and a master welder. Music surrounded her from birth, her mom waking her each morning singing the traditional religious song, "Rise and Shine." On Sundays at Wirt Baptist Church, music and service to God became intertwined.

“We’d sing Bible songs. We’d sing hymns. We’d make up songs,” Kathy says. “Music just became a tapestry.”

In Madison schools, Kathy struggled to fit in as a “short and quirky” country kid. She tried to find her tribe through basketball, baseball and volleyball but did poorly in all. Over dinner one night, her grandmother told her, “Your gift is in music, not in sports.”

She joined show choir and school musicals — and found a place to belong.

Two special teachers nurtured her talent and told her to chase what she loved. She realized she loved teaching, too. She combined the two and studied music education at Indiana State University, then Indiana University. In her senior year, she married chemist Bryon Sego, a drummer who played in a band with college friends.

The couple settled in Madison and had two kids, Hunter and Katie. Kathy mostly stayed home, teaching private voice lessons, judging musical competitions and helping choirs, including Austin’s on occasion.

Also: Austin's journey from drug addiction to hope: A story America needs

When Austin's choir director, a former student of Kathy’s, left in 2011, he pleaded with her to take his place, saying: “My kids need you.” It struck at her core belief that God gave her a talent so she could serve those in need.

She agreed to talk to administrators about teaching at the high school and its attached middle school, but she assured her husband she wouldn’t take the job. Their children were entering their teen years. And with their son also having diabetes, Bryon wanted someone at home.

But she called him after the interview, saying “Bryon, I start school in two days. Surprise!”

People immediately asked: Why Austin? The one-stoplight town had a growing reputation for poverty, drugs and all the ills that go with them.

Kathy countered that every place has problems. She described the clean, spacious school with its big choir room and impressive auditorium.

She said Austin had plenty of good, hardworking people and intact families that weren't involved with drugs.

She told them of the students who find the school a safe haven, full of caring adults. The haven where the students treat it so well there wasn't even graffiti in the bathrooms.

But the negative talk grew louder when the HIV outbreak struck four years later, propelling the town of 4,200 into national news. The disease ultimately sickened 235 people, pushing Austin’s 2015 HIV rate as high as countries in Africa.

Stigma grew, and stung.

A girl on the track team ran to Kathy one day. Through tears she asked about a visiting team: “Can you believe they didn’t want to use our bathrooms because they were afraid they might get AIDS?”

Members of other choirs whispered at a competition: “Be careful, you don’t want to go around those kids. They have AIDS.”

Kathy didn’t blame the out-of-town students — she blamed their parents for failing to let them know that HIV isn’t spread through casual contact and that the kids didn’t have it.

She took it upon herself to educate acquaintances who asked if she wore gloves at school.

Part two: How an Austin pastor transformed his addiction into a mission of faith

HIV has hit close to home for a few students whose relatives were diagnosed. And far more kids were familiar with its root cause: addiction. Some saw it in their families.

Students overwhelmed by these problems sought Kathy out before and after class.

They called and texted so often that Bryon nicknamed her “my little teenager” because she was on the phone so much.

She opened up her home, where students also got to know Bryon, who volunteered to help out in any way he could.

"It's almost like she's on a mission with these kids. ... She is truly a place of calm,” Bryon says. “The pressures of life can be too much. With music, it just allows people to jump outside who they are and express themselves. Through this art form, they come alive, and it gives them the confidence to do other things."

Choir became a sanctuary, even a lifesaver. Some kids told Kathy the only reason they stayed in school was to avoid letting her and the choir down. A girl who'd contemplated suicide told her that choir gave a reason to live.

"Kids are vulnerable here, but I don't dwell on it. I don't let them dwell on it ..." Kathy says. "If you can't move beyond that, you're always going to be stuck."

The longer Kathy stayed, the more her love and anguish for the kids grew, sometimes overwhelming her. She couldn't hide her emotions from the kids.

Kathy is allergic to her own tears, so her students would often see her face break out in blotches.

The love left her torn.

When her daughter Katie was up for homecoming queen her senior year, Kathy chose to attend a show choir competition in Northern Indiana over the Madison basketball game and homecoming ceremony, thinking that disappointing one child was better than letting down 30.

She changed her mind only after seniors in the choir refused to go. Instead, half the choir went to Katie’s school to cheer her on.

That spring, Katie joined Kathy and Bryon when the show choir competed in a national championship in Chicago. It was the first time they’d ever made it that far. A big-budget California team beat them, but just being in the same league showed them what’s possible.

The theme of their show was overcoming obstacles — the closing number: “Unstoppable.”

Music lost and found

That song could have been written for Kasey Brandenburg.

Addiction shaped her life from the beginning, though she didn't know it at first. As a tiny girl living with her grandmother, she saw her parents as loving and perfect. Her earliest memories are of listening to her dad’s singing and drumming and her mom’s soulful voice as she strummed a guitar.

Kasey danced to their music.

But she lost her mom, Kelli Marie Wolfe, when she was 7. She didn’t know until years later that Wolfe had overdosed.

Her father, Elvis Wayne Brandenburg, wasn't at the funeral because he was in the Scott County Jail on theft charges. Shortly after getting out, he was locked up again for theft — Kasey believes he stole a birthday present for her. He came straight to see her after his release a year later, only to overdose on pills two days later and die.

Depression replaced music.

But only for a while.

In middle school, Kasey took a concert choir class taught by Kathy, who insisted: “You have to do show choir.”

She joined in eighth grade, and Kathy saw a latent performer in the closed-off preteen. She pushed so hard that Kasey felt picked on and singled out for singing wrong notes.

By the end of the first year, though, Kasey was dancing in the front row and singing a solo. She realized the pushing meant Kathy saw something special, something Kasey longed to see in herself.

Over time, Kathy became more like a parent than a teacher — becoming one of the many people in town who pitched in to help raise Kasey.

Part three: After the crush of a meth arrest, an Austin teacher finds her light

By the time Kasey was in high school, Kathy was giving her rides to school and sometimes bringing her food. She slipped money into Kasey's purse, knowing she struggled with part-time jobs at places like Subway and Huddle House.

"She's always been a mother role to me," Kasey says. "She completely took me under her wing, and that's why she was also very hard on me."

Kasey often took Kathy for granted, talking to her the way teenage girls often talk to their moms: “Any way I wanted to.”

She knew Kathy would believe in her anyway.

Moms usually do.

But others expected her to follow her parents' path.

Things got even worse when Kasey decided to move in with her boyfriend at 17 — about the age her mom had moved in with the guy who would later become the father of her half-sister. That's when her mom, a bold, creative girl much like her, fell into drugs.

“Don’t do this,” Kathy begged.

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” Kasey snapped. “It’s my life!”

Kasey moved to Austin's notorious Rural Street. She and her boyfriend watched people stagger around outside crumbling homes, “wiped out” from shooting up. Women openly sold themselves for a fix.

At school and in town, Kasey felt some people were “looking at me like I’m going to be nothing.” It got harder to muster the energy to change their minds.

She rolled into show choir tardy or half-asleep because she stayed out late, sometimes with kids who used hard drugs. Kasey never used them. She thought maybe she could save those kids by sharing what she'd been through.

Kathy didn’t see it like that. She worried each time the school called Kasey’s name for random drug tests for kids involved in extracurricular activities. She prayed with each dollar she handed her: God, I hope she’s using this for food.

Kasey kept pushing boundaries. She flouted the dress code by wearing jeans with holes in them and she pierced her nose. She left school one day without anyone signing her out, arguing she had no parents to do it. The loudspeaker frequently blared: “Kasey Brandenburg, please come to the office.”

Kathy pleaded with Kasey: "What are you doing? You've got to go to college and get out of here."

Kathy resisted colleagues' attempts to discipline Kasey by assigning “Saturday school,” telling them: “She doesn’t have a mom. I’m gonna be her mom!”

She once argued within earshot of Kasey: “She’s a star" who needed show choir because it was "keeping her away from the bad stuff.”

And it was.

On stage, the world fell away. Kasey was that little dancing girl once more.

“You just completely lose yourself in the music and the dances that you’re doing and the words that you’re singing,” she says. “It’s hard for me to do one of the shows and not cry.”

Truck driver Donnie Lewis, a close friend's dad who took Kasey into their family's home when she broke up with her boyfriend, called show choir "a tremendous influence."

Kasey says Kathy and Donnie were part of a large "support group" of parental figures in Austin who played a part in raising her, helping her grandmother, uncles and other family members. In some ways, Kasey says, it's like the town raised her.

"She's a remarkable young lady," Lewis says. "The life she was dealt is gonna be a distant memory for her. Where you come from isn't where you have to end up."

Kasey's half-sister, Melissa Shuler, 21, says she's grateful for all those who helped Kasey, who she hopes "soars as high as possible."

"It takes an army. So there were always teachers, coaches, counselors, friends' parents, Kathy, so many people," says Shuler, who worked in the stage crew while she was in high school. "Kathy was a terrific influence. She helped Kasey with her voice. Kathy helped her be more powerful."

Bolstered by loved ones, Kasey let herself wonder about college when a show choir clinician from Ball State University visited Austin.

But then she thought again. Even if she could get in, she could never afford it.

She sometimes told Kathy she didn’t want to go.

“Yes, you do,” Kathy insisted. “You’re going to regret it if you don’t.”

Building dreams

Go all-in for what you want. That's Kathy's mantra for all her kids:

For freshman Bentley Mahaney, an aspiring artist and musician who lives with his mom, stepdad and three siblings in the house his great-grandfather built. His mom saw her share of drugs, poverty and abuse when she worked in child services in town and knows show choir offers the opposite: love, community and pride.

For sophomore Mario Martinez, the son of factory workers and a relative newcomer to the choir who Kathy says has come "so stinkin' far" by practicing two hours each day.

For senior Keegan Young, who juggles choir, school and soccer with night shifts at McDonald’s, and whose mom wants him to have "dreams as big as he is” that will take him far beyond Austin.

"I love them all," Kathy says. "The moment you walk into this room, you're mine."

Austin’s first day of school began in fog. But the sun gradually cut through, illuminating a sign on Main Street that read, “God is in control.”

Kathy arrived early, in a colorful summer dress and high heels. She barely had time to drop two big bags of goodies in the choir room before Audrey Morris ran up and hugged her, exclaiming “I love you, Mom!”

Other kids streamed in for a welcome, and Kathy's high-pitched voice filled the room.

“Blake! How are you, honey? Happy first day!”

She handed each kid treats – M&M’s to let them know they’re “marvelous and magnificent,” and No. 2 pencils “because you’re No. 1.”

The choir room bustled all day.

The first of Kathy's back-to-back classes was middle school show choir. She informed the kids they'll be together for years, "so be kind to each other, help each other out … and know that I love you no matter what.”

She stayed in the room for lunch, chatting over cafeteria food with kids who eat there, too.

Part four: I watched disease and despair grip Austin. Now hope is breaking it free

Then it was back to teaching. High schoolers gathered in a dressing room to chill, then scrambled to risers for their last-period show choir class.

“Everyone is here because I saw something that maybe you don’t see,'' she told them as they faced a huge mirror. "So you need to believe in yourselves.”

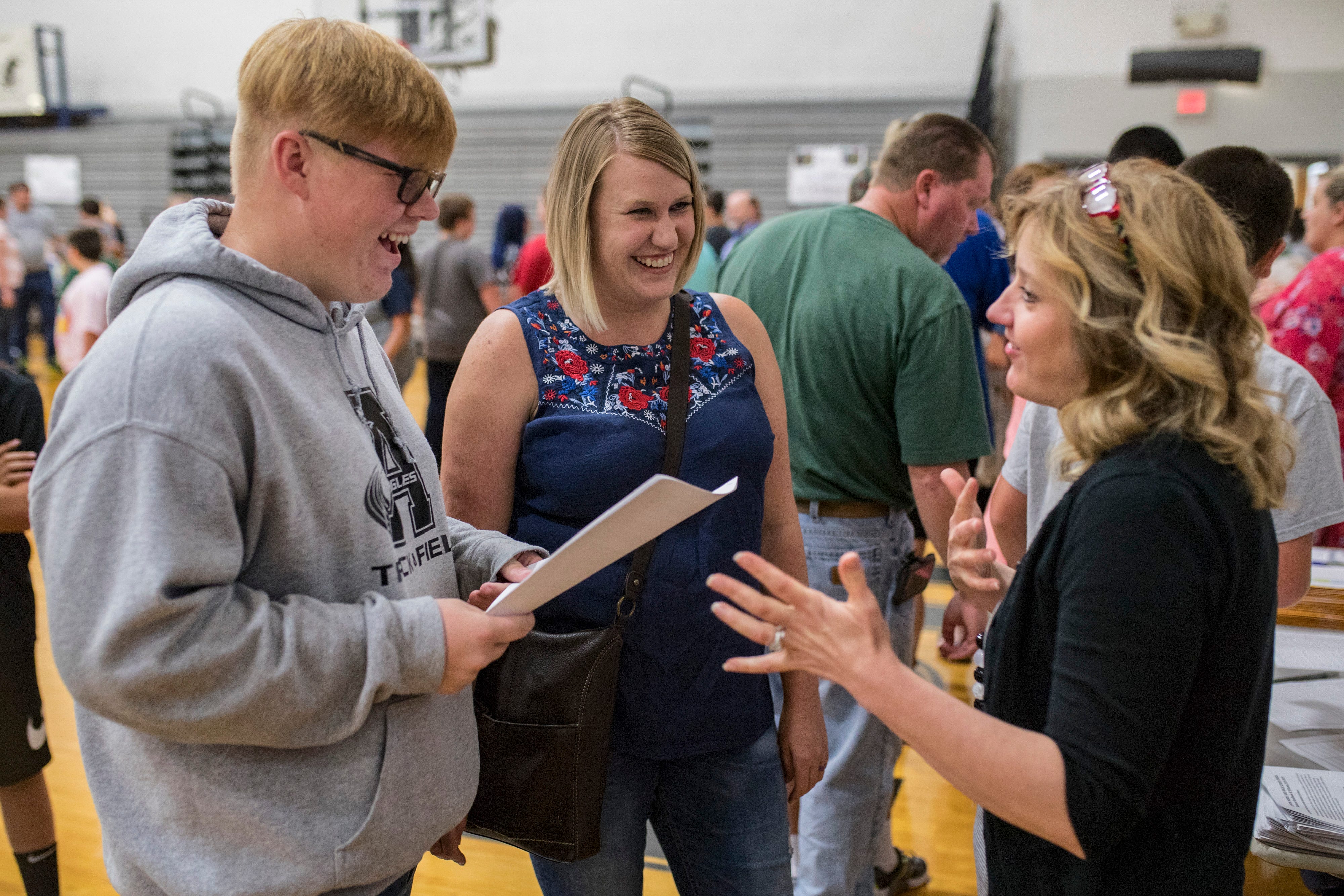

Two months later, the kids had their first performance, at a 20th anniversary dinner for the Scott County Partnership, a community-building organization. Kathy was nervous, but the kids belted out their songs and danced with precision. People swayed in their chairs and tapped their feet. Kathy nodded and smiled.

Later, the kids rushed to dismantle the risers and load them into a U-Haul. Junior Sydney Stewart dropped a metal post on her ankle. Friends carried her to a safe spot, where the whole choir gathered around as Kathy massaged Sydney's foot.

Kathy yelled to the group: "I'm uber, uber proud of you!"

She's generous with praise when the kids earn it. But she sets her expectations high to counter the barrage of low expectations she knows they face. Like a football coach, she makes them do five push-ups for failing to count dance steps. She warns, half-jokingly: “Don’t miss practice unless you’re dead,” and "Don't do drugs or I'll have to hunt you down and put you in my basement."

As the bell rang at the end of school one day, she yelled to her kids: "Make good choices. MAKE GOOD CHOICES!"

And she tells kids choir, like any community, is only as strong as its weakest member — the stronger ones must help others.

“It’s about pride,” she says. “Remember, you have Austin on your shirt.”

On her drive home, Kathy assesses each day, always finding some way she failed her kids and mulling second thoughts. Was she too negative? Too hard on someone?

She returns to school the next day and tries again.

Sophomore Tyler Henderson, T-Bone for short, considers Kathy “a huge role model” and hopes to follow her into teaching. He’s already talked to her about music education at Ball State and is getting some early experience next to her on the piano bench and helping with middle school choir.

For Dimensions, he hones his singing in the shower, practices dance moves in front of a mirror at home, and logs hours in the choir room before and after school — always thinking about the next class, the next performance, the next step.

That's another lesson from Kathy: Focus on the future.

As the kids belt out lyrics from Scott Alan's "The Distance You Have Come," she yells: “Are you listening?”

And when you reach that day,

When you've conquered what's behind you,

Don't forget the fight it took to get you here.

With enough pushing, Kathy knows it’s possible to bridge a seemingly impossible distance and move forward with hope — for the kids and for Austin.

Kasey is proof.

She kept her grades up and got into Ball State with lots of financial aid. She's thinking about graduate school, too.

Two days before leaving for Muncie, she was back in the choir room. She watched friends learn their moves, remembering all the dancing she did in this room.

Between songs, Kathy led her into the school's parking lot, opened her trunk and pulled out dorm-bed-sized sheets that once belonged to her daughter, Katie.

She half-jokingly warned Kasey not to let anyone else under the sheets.

“You need someone to tell you this,” she said.

She continued with her motherly advice:

“Don’t buy books. Rent books.

“And call me. You know how to get a hold of me.”

She looked up into Kasey's eyes.

“I love you,” she said, tears welling. “Make good choices.”

She pulled Kasey close one more time, and let go.

Laura Ungar: 502-582-7190; lungar@courier-journal.com; Twitter @laura_ungar. Support strong local journalism by subscribing today: courier-journal.com/laurau.