The idea of imposing a “land value tax” in the District pops up from time to time. Rick Rybeck at Just Economics has been promoting land value taxes for as far as I could remember. Both the 2013 Tax Revision Commission (here) and the 1997 Tax Revision Commission (here) gave consideration to a land value tax as a means of restructuring real property taxes. The 1997 study is especially worthy of a read as it walks the reader through many compelling arguments for why the District should consider a land value tax (equity, efficiency, and denser development) and how the tax incidence could be redistributed across the city when overall tax revenue is held constant.

The idea has recently returned to local policy discussions. In March, Daniel Herriges called for a land value tax in D.C. in Greater Greater Washington, correctly pointing out that the District’s current real property tax regime penalizes commercial development, especially in parts of the city that needs development the most. In September, Urban Institute researchers identified a land value tax as a “high-potential” tool to increase housing supply in the D.C. region.

Can the District increase density and expand the housing supply through a land value tax? A comparison of zoning limits to what is already built suggests: not where development is needed the most. Our analysis suggests that a land value tax can increase the pace of densification in some parts of the city, but—due to zoning restrictions—will do little to increase the housing supply in parts of the city where supply is already short.

Even with more permissive zoning, the administrative difficulties in implementing a land value tax could be great. The District’s current real property tax assessment regime does not always distinguish between land value and building value and overhauling how land and improvements are assessed could cause taxpayer angst and anger.

The tax regime can help incentivize development, but it cannot address the underlying problem of restrictive land use practices. Still, a land value tax could be a worthwhile reform. The progressive nature of a land value tax, especially for residential properties, can create legislative buy-in for its implementation and help break resistance against development. Importantly, a mental accounting of what land value taxes might mean for the city also helps highlight how its tax regime help or hinder future development.

What is a land value tax?

Land value tax refers to a property tax regime where the tax is imposed on only the value of the land and not to the value of improvements—the real estate jargon for whatever is built on the land. A variation on the same theme is a split-rate tax (sometimes called the graded tax) where both the land and the improvements are taxed, but land is taxed at a much higher rate.

While originally proposed in 1879 by Henry George in Progress and Poverty as a much more efficient alternative to all other forms of taxation (mainly because you cannot move your land elsewhere, or do anything with it but put something on it), today, the resurrection of the land value tax is not primarily for the purpose of reforming the tax regime to increase efficiency and equity, but to increase density (see here, here, and here). The rationale is straightforward: At the extreme, when improvements are not taxed at all, there will be a strong incentive to increase density because this will reduce the average tax on the entire property (land and improvements combined). The bigger the gap between the land tax rate and the taxes imposed on the improvements, the greater the incentive to develop. [1],[2]

How would a land value tax work?

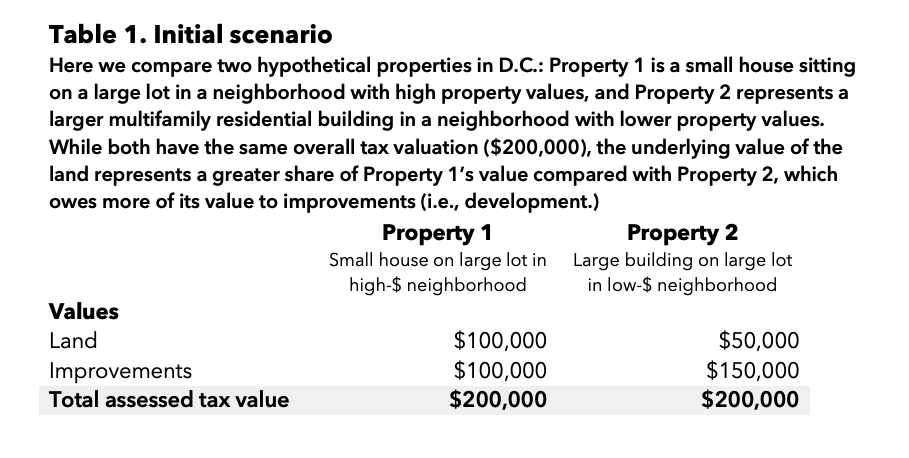

Imagine two residential properties [3] in two different parts of the city: one, a small house sitting on a large lot in a neighborhood with high tax assessments (like a single family home in Friendship Heights) and another, much larger building sitting in a lower-valued neighborhood (like a small multifamily building in Deanwood). For illustrative purposes, let’s not worry about the lot size and assume that properties are valued as shown in Table 1: Property 1 has land valued at $100,000 and improvements valued at $100,000, while Property 2 has land valued at $50,000 and improvements valued at $150,000. Both have a total assessed tax value of $200,000.

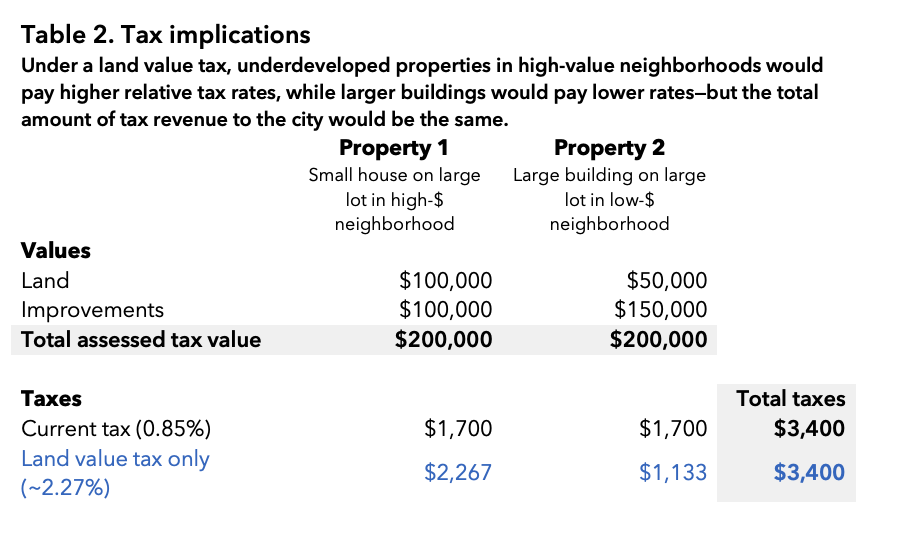

Under the District’s current tax regime, both properties pay the same amount of real property tax. Ignoring other factors such as the homestead deduction and the tax cap (again, for illustrative purposes), each property, taxed at 85 cents per $100 of assessed value, would pay $1,700 per year, for a total tax revenue of $3,400 from both properties.

Now consider the scenario where the tax on improvements is abolished, and tax is imposed on land only. To receive a similar amount of tax revenue, the city would have to increase the tax rate on land to (roughly) $2.267 per $100 of assessed value. While the total tax collections remain the same, the burden is no longer equally shared. The underdeveloped land in the higher-value neighborhood now pays two-thirds of total collections, while the property with a larger development but a lower-valued lot pays one third.

Important consequences follow from such a change in tax policy.

First, tax burdens shift to the parts of the city with better amenities. Capitalized in land values are the positive impacts of all sorts public and private investments that generally have little to do with individual owners. Land by a metro station (public sector action), in a safe neighborhood (public sector action), and in close proximity to job centers or private amenities like retail and restaurants (largely private sector actions)[4] is valued at a much higher amount than land far away from these amenities. Under a land value tax, the owner has little choice but hand over some of this added value to the government.[5] To the extent that these returns are used productively—for example, by investing in under-resourced parts of the city or in infrastructure—the outcome is overall a good one.

Second, owners of underdeveloped land would find an incentive to develop. For example, by tearing down the small house and replacing it with a duplex or a triplex, the owner of our illustrative Property 1 can add more value without any tax increases, and thereby reduce the average tax rate on the property.

Third, the demand for land in lower valued parts of the city will increase, shifting economic activity to where it is needed the most. This already happens, but a land value tax will likely increase the pace at which development shifts to parts of the city with lower property values. Cheaper land with no tax penalty for developing it would increase developers’ interest—they could change entire city blocks, adding hundreds of housing units, without a major tax increase. This is particularly important for the District, since economic development (and access to amenities) are so uneven across the city.

But to get these benefits from a land value tax, the following must hold true: First, land use practices should be permissive enough to allow for further development. This, as I will show, is also not the case for much of the city, especially in places where density is low. Second, the city should be able to correctly assess land values separately from the buildings that sit on the land. This is currently not the case and getting there will require significant administrative changes and taxpayer education. And finally, the landowner should not be able to pass on the tax to others.[6]

Restrictive land use regulations limit the potential development impacts of land value tax

A land value tax can serve as a great incentive for further development and densification. However, this only works if there is room for growth. If land use regulations are too restrictive, then the tax will only be a stick (higher taxes for being in D.C.) and not at all a carrot (lower effective taxes that encourages densification).

How much room exist for further development under the District’s current zoning regime, then, especially in residential zones? This is a very pertinent question—not for only land value taxes, but in the context of updates to the Comprehensive Plan and Mayor Bowser’s Order to add 36,000 homes with recently announced neighborhood-specific targets.

It turns out, determining whether “excess” capacity exists for each tax lot is quite tricky and requires a lot of assumptions. By definition, almost every existing property is under the zoning limit. The relevant question is whether enough room exists under present zoning to even consider the decision to develop more.[7]

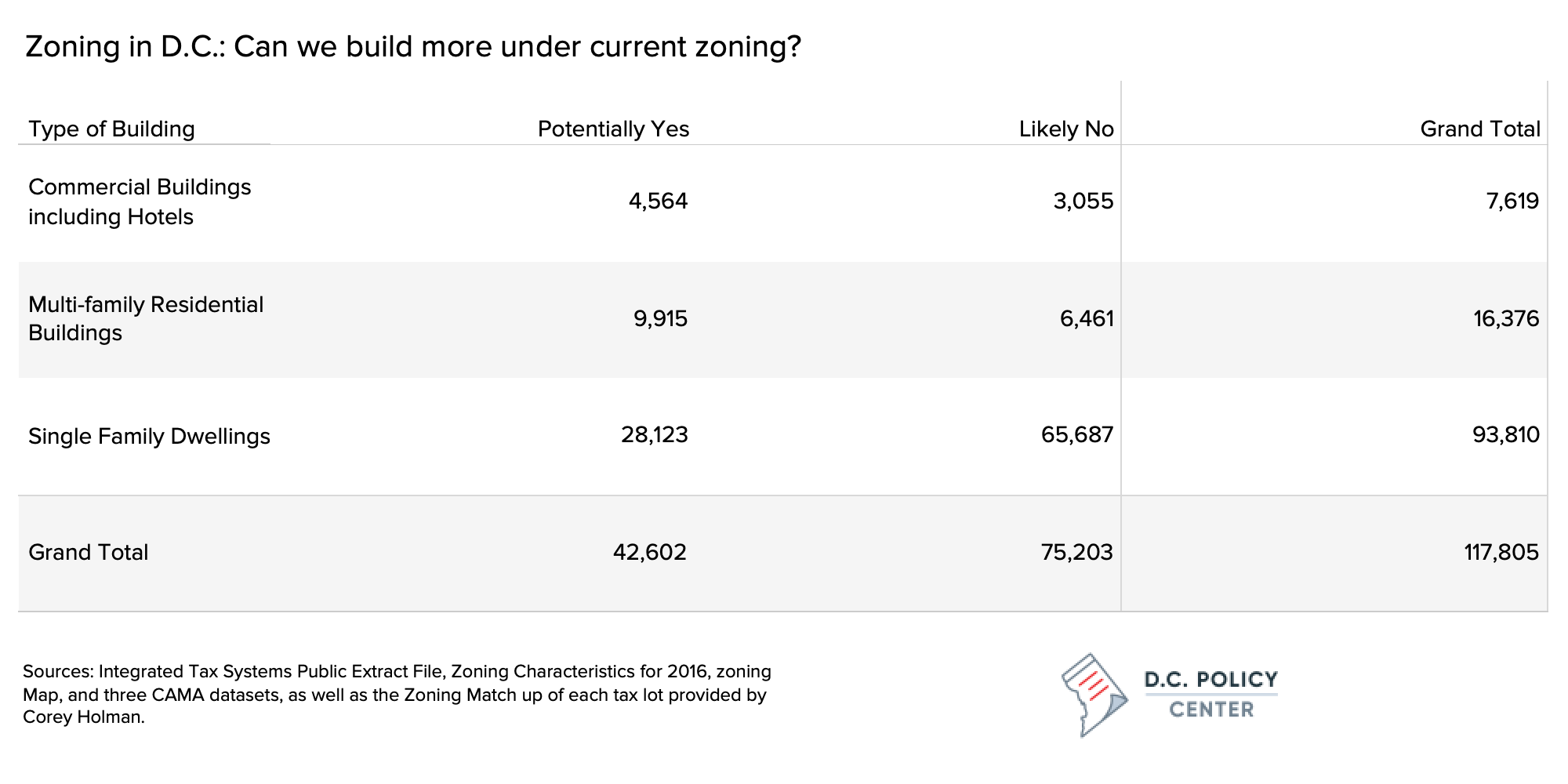

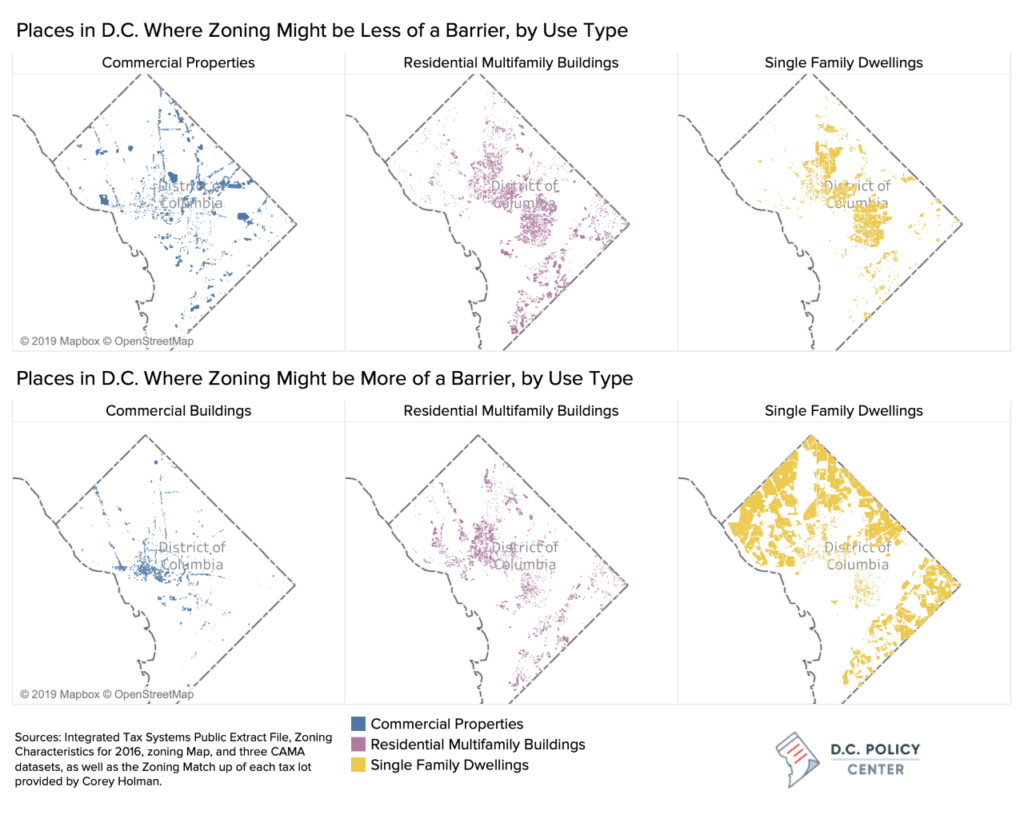

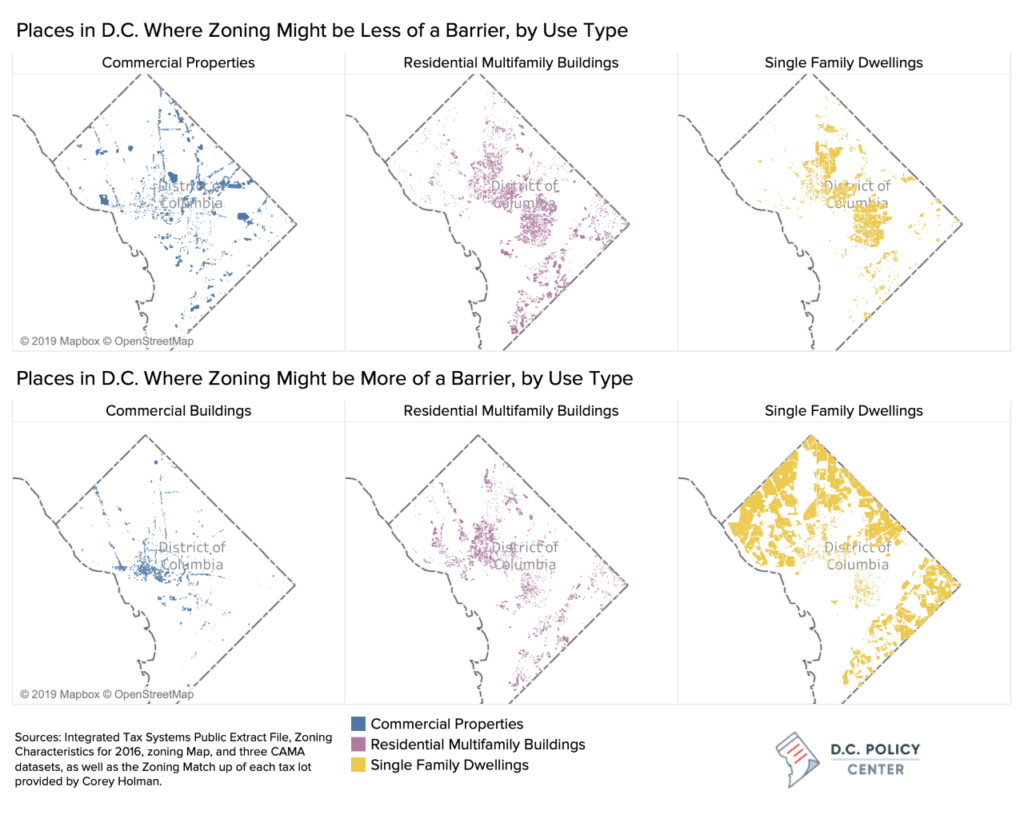

Of the nearly 118,000 tax lots for which we could make a determination,[8] only about 36 percent potentially could have room for growth under current zoning laws. Of the nearly 7,600 commercial buildings in D.C. (commercial office buildings, hotels, retail establishments, investment properties, and so forth), nearly 60 percent potentially have sufficient room under current zoning for redevelopment. Similarly, about 60 percent of D.C.’s 16,376 multifamily residential buildings (apartments, flats, conversions, and cooperatives) can be expanded a bit more under current zoning.

Even this high-level summary of our findings shows that the real impediment to further residential densification across the entire city is the large number of lots occupied by single-family residential housing. We found 93,835 such lots and estimate that 71 percent of these face a high zoning barrier to increasing density in any meaningful way.

The binding restriction for single family residential lots is not the lot size (in contrast to lots with commercial and multifamily buildings) but the number of dwellings allowed on these lots. While many single-family homes in the District are constructed on large lots, they are often in zones where only detached housing is allowed (R-1-A, and R-1-B). We found 21,000 homes just in these zones, which have no hope for densification even when there could be plenty land. For these, the only path to adding density is by way of an Accessory Dwelling Unit, such as a basement rental or small standalone apartment (sometimes known as a granny flat).

In contrast, only about 29 percent of the District’s single-family residential units appear to have room for potential densification through the addition of new units.

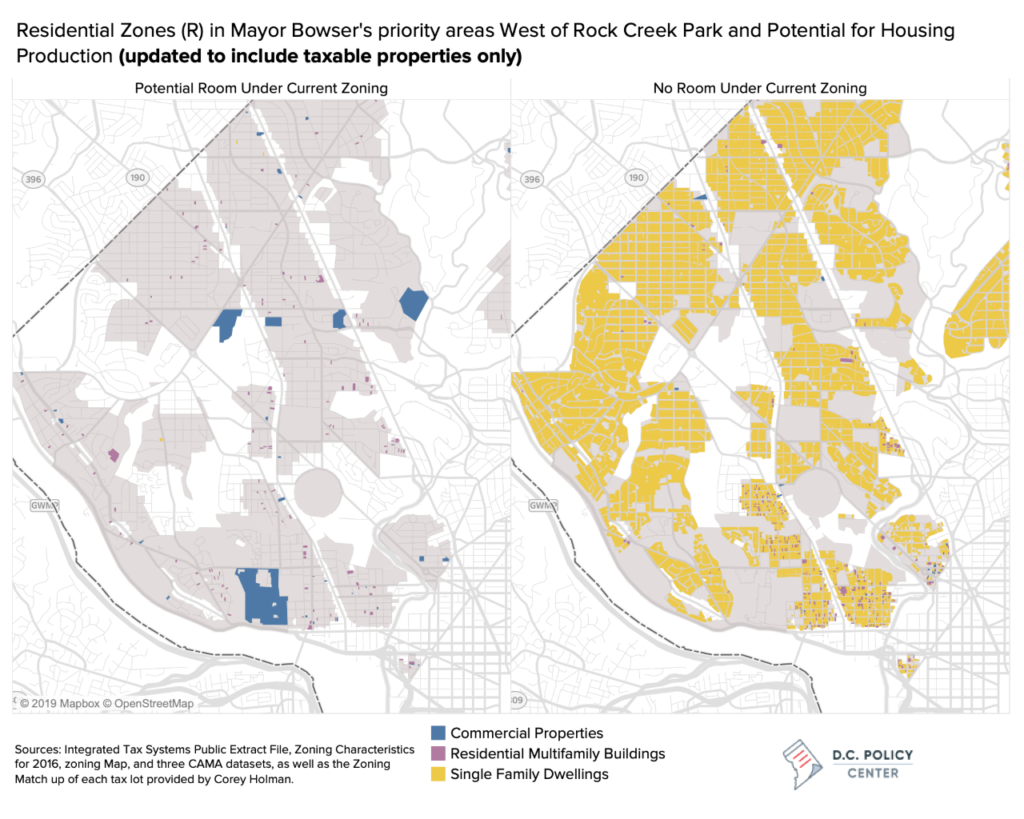

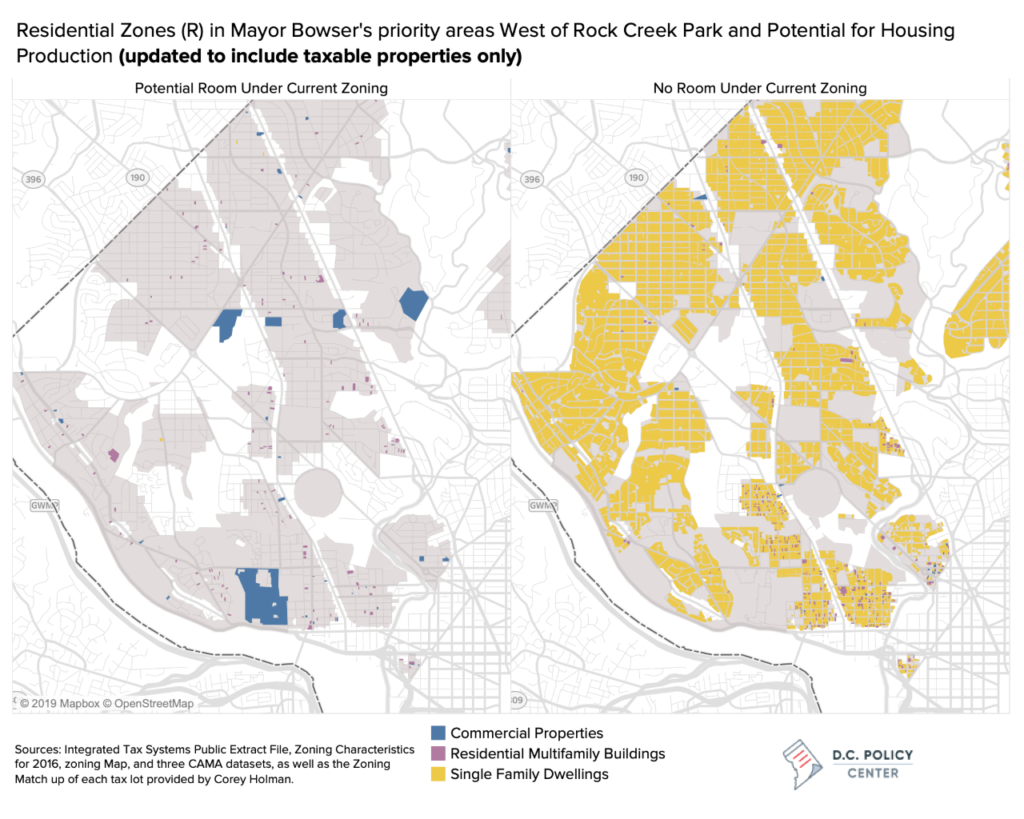

Take, for example, the parts of the city zoned for residential use (beginning with the letter R in the Zoning Code) in neighborhoods west of the Rock Creek Park. For these neighborhoods, Mayor Bowser is calling for the creation of 1,910 new affordable housing units, mostly through new construction. Our analysis shows that, unless the District relaxes single-family zoning in these neighborhoods (gray shade in the map below), the new units will have to come from lots currently under commercial use (blue lots) and not existing single family lots (yellow lots).

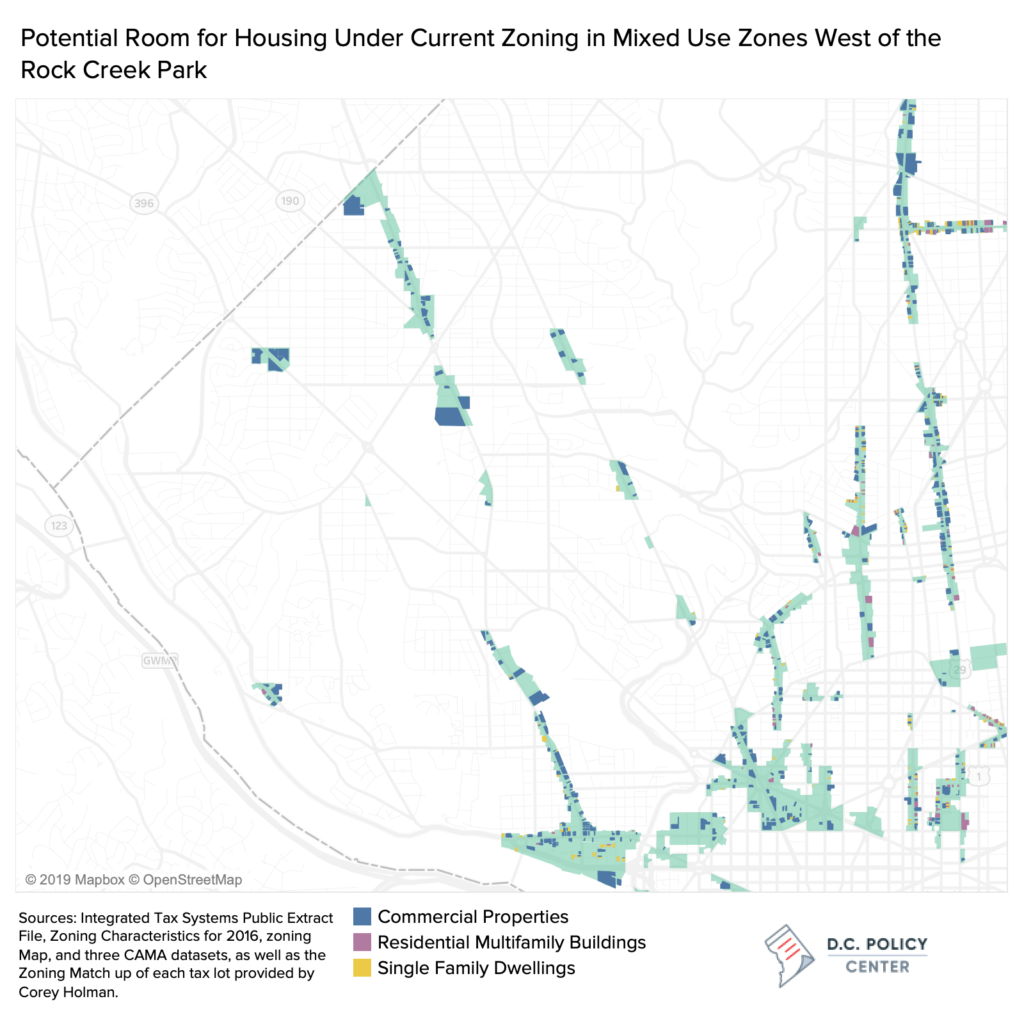

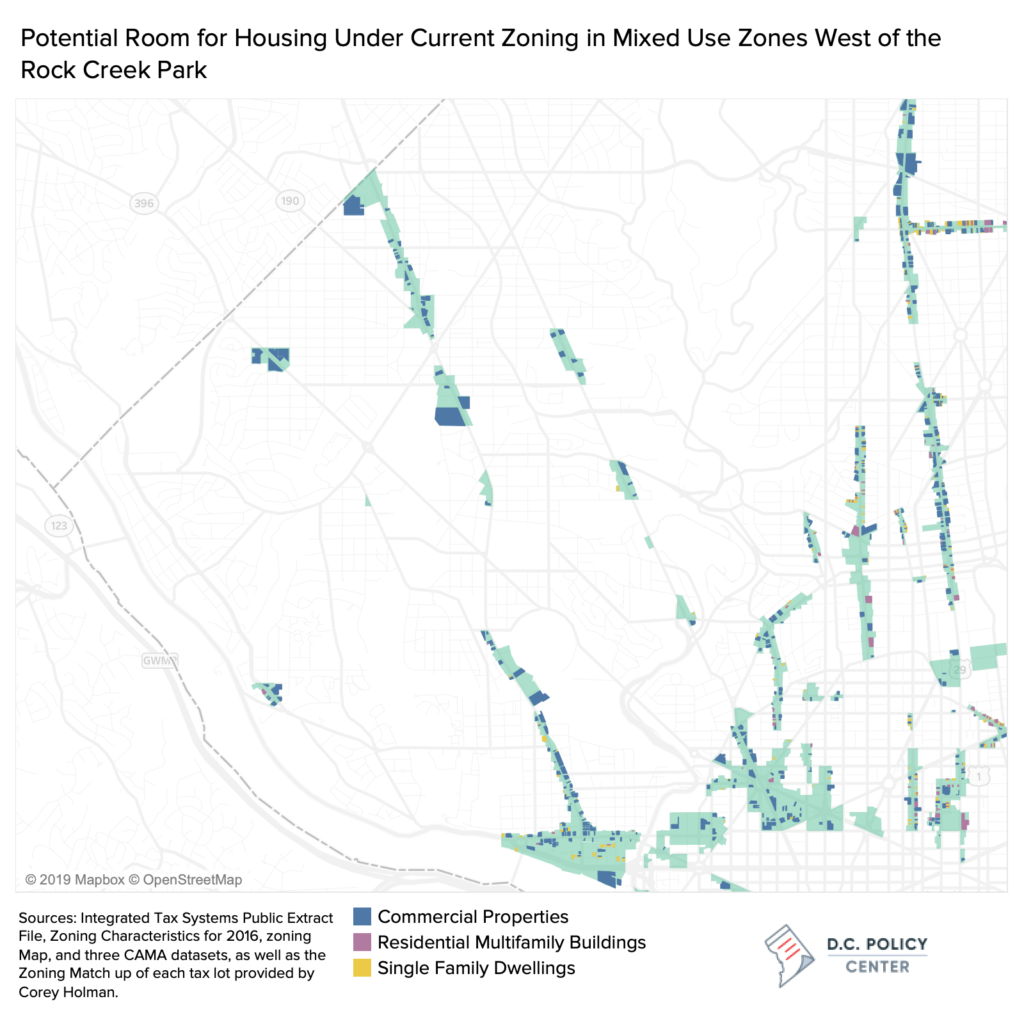

In neighborhoods west of the Rock Creek Park, high-density mixed-use development along transportation corridors can certainly help with creation of new housing units. But current zoning does not allow for it: At present there is little room for growth for parts zoned as mixed use (teal in the map below) along Connecticut Avenue. There is room for growth along Wisconsin Avenue, but zoning generally limits the area to low density (whether residential or commercial). The Office of Planning’s proposed amendments to the Future Land Use Map can certainly clear the path to up-zoning, and consequently, increased supply: the proposed changes include allowing residential development in places currently zoned for commercial along Connecticut Avenue and Wisconsin Avenue, and allowing for more density especially in places near Metro stations.

The neighborhoods west of the Rock Creek Park demonstrate best how land value tax might be a deterrence for inclusive development when zoning becomes too restrictive. To wit, Mayor Bowser’s current affordability target (1,910 homes) is greater than the target for net new housing (1,260). If development is impeded, affordable housing necessary to meet these targets must come from preservation. And with no room to grow, a land value tax will make preservation more expensive.

On the other hand, a land value tax could bring much positive change in mixed-use zones along Georgia Avenue, and to some extent along Rhode Island Avenue between 13th St. NE and South Dakota Avenue NE as these areas present the greatest opportunities for redevelopment under current zoning. A pilot land value tax in these parts of the city could be an interesting experiment with likely positive outcomes.

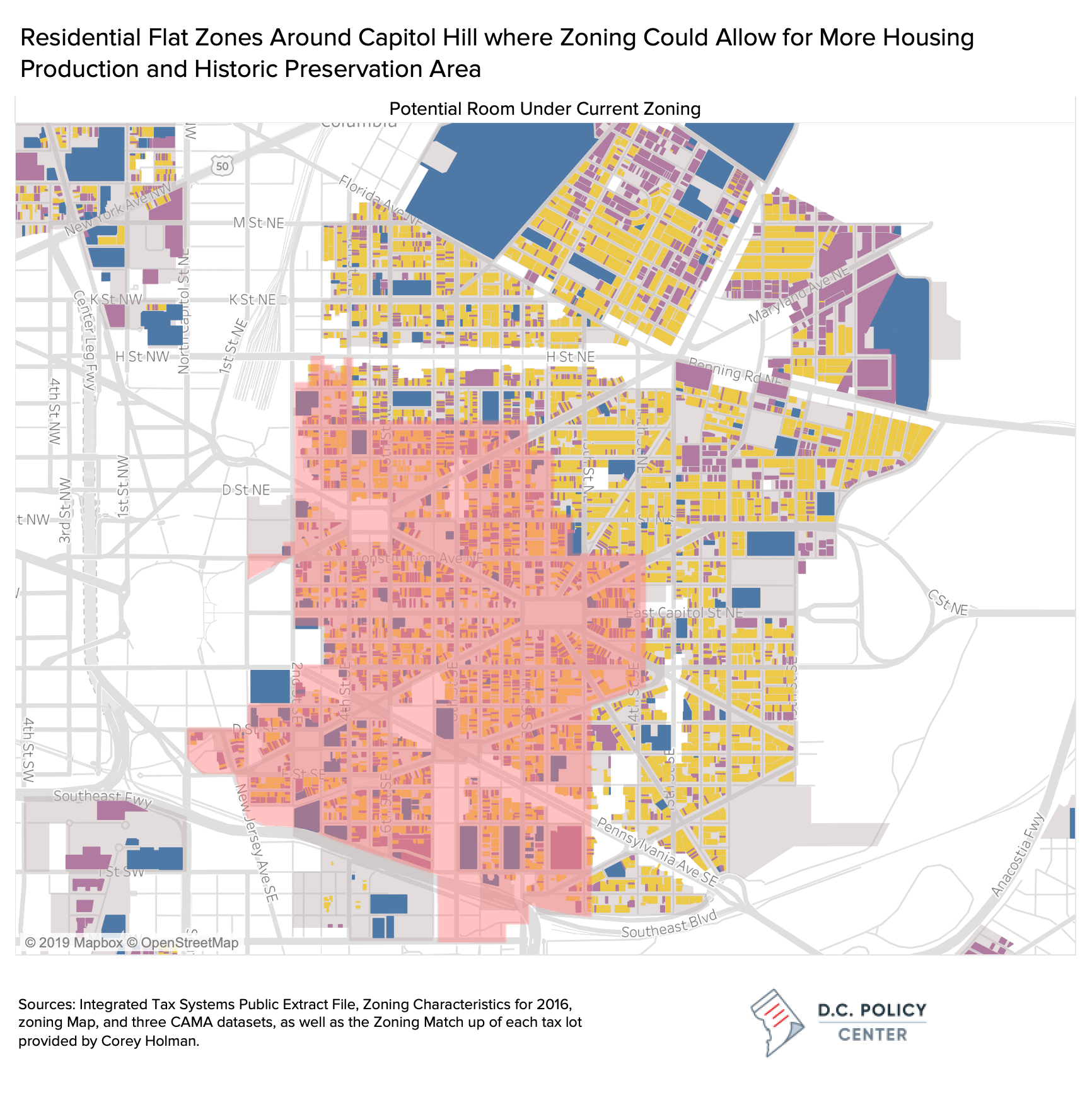

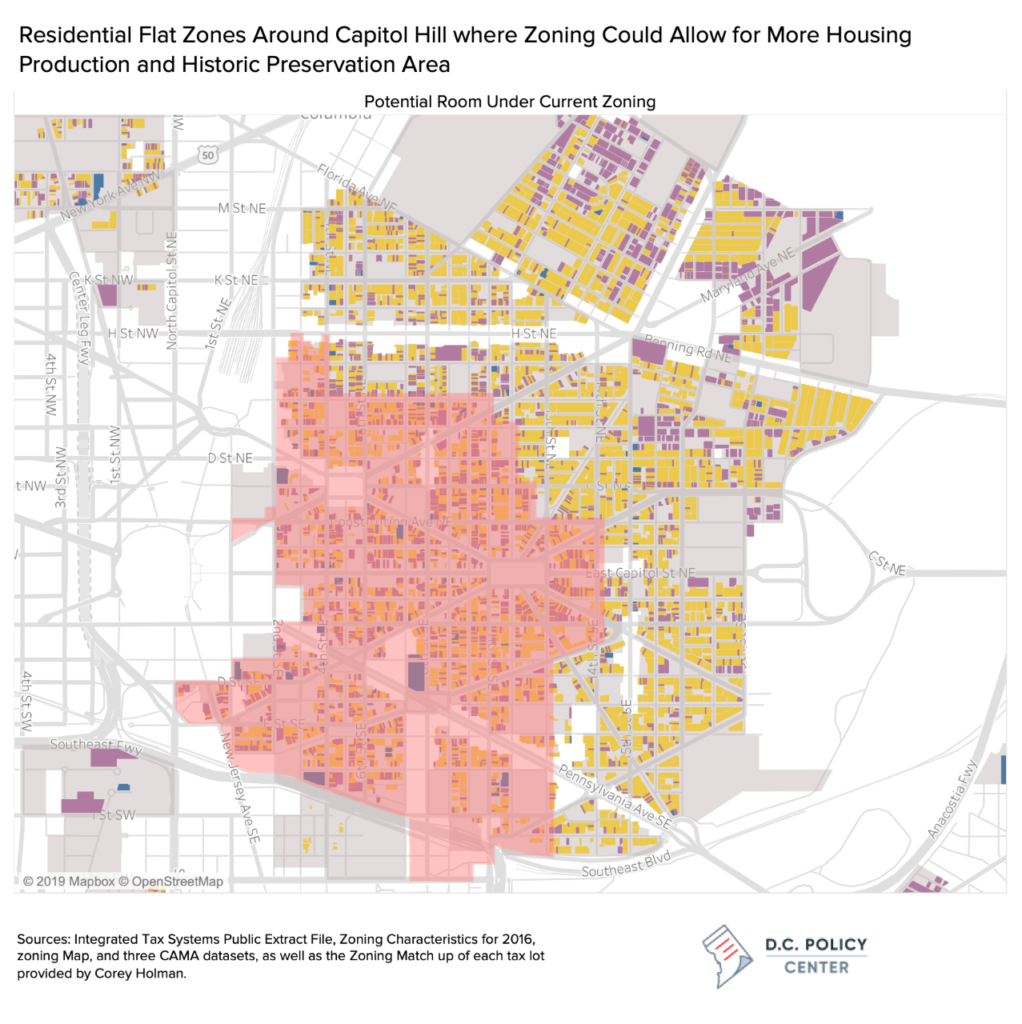

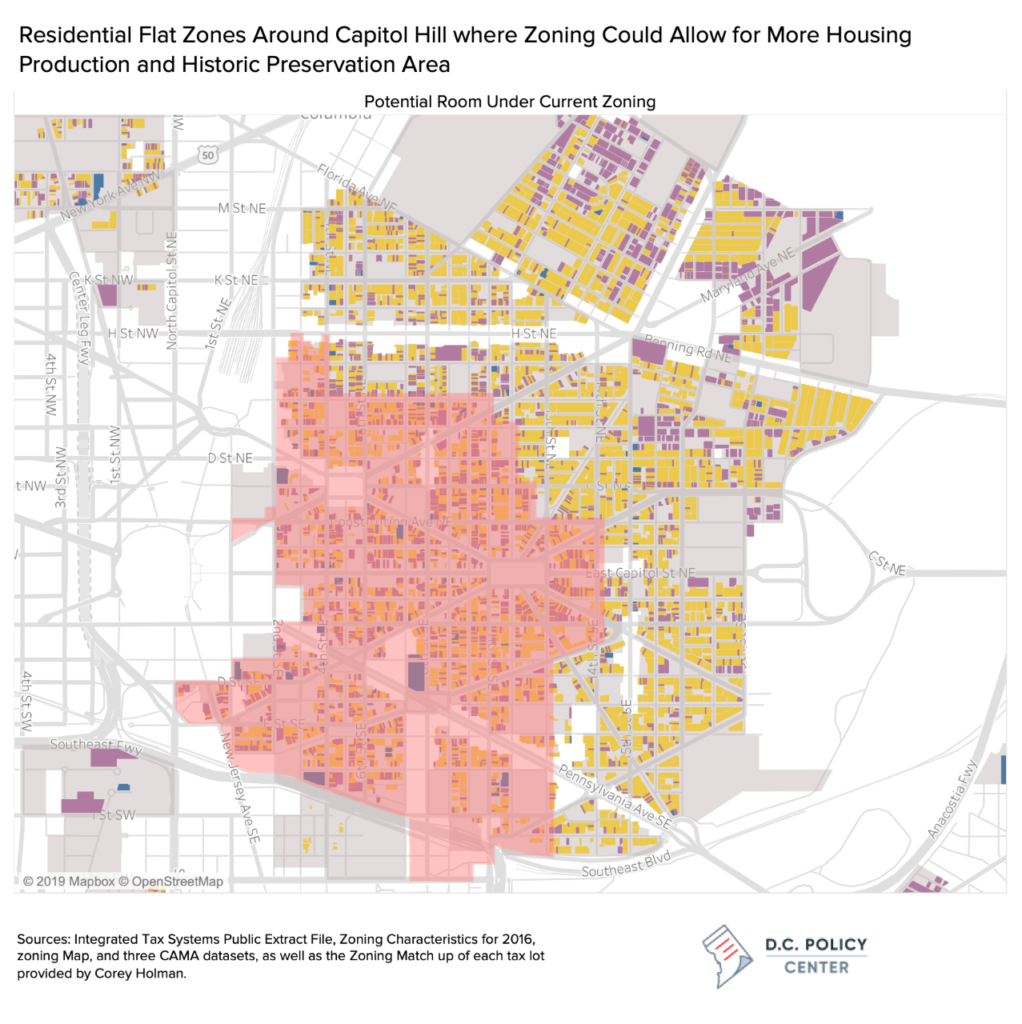

Are there parts of the city where a land value tax could help make real progress towards meeting the Administration’s housing targets? Mayor Bowser’s second-highest affordable housing target for 2025 is in the Capitol Hill area, with an affordable housing production goal 1,120 units. The maps below show the tax lots that are in Residential Apartment and Residential Flat zones, where there is likely room for further development and densification. The maps below show that there is significant opportunity for residential and commercial development in much of the Capitol Hill area, and for this lots a land value tax could be a real incentive for development. However, redevelopment in lots west of 13th St NE would likely be limited by historic preservation requirements (shaded red), which presents significant barriers to development. For the remainder, a land value tax can be a real incentive for development.

The District’s Real Property Assessment processes do not allow for an easy transition to a land value tax.

The imposition of a land value tax would require separate assessments of the value of the land and the value of improvements on it. [9] A review of city assessor reference materials shows that the District’s assessment processes do not currently make this distinction.

While a bit in the weeds, it is worth understanding how D.C. currently assesses real property and how these practices must change under a land value tax. Real property tax assessments already create a lot of taxpayer anger and confusion, further administrative changes to how values are reported could create even more angst and anger and make the implementation of a land value tax politically difficult.

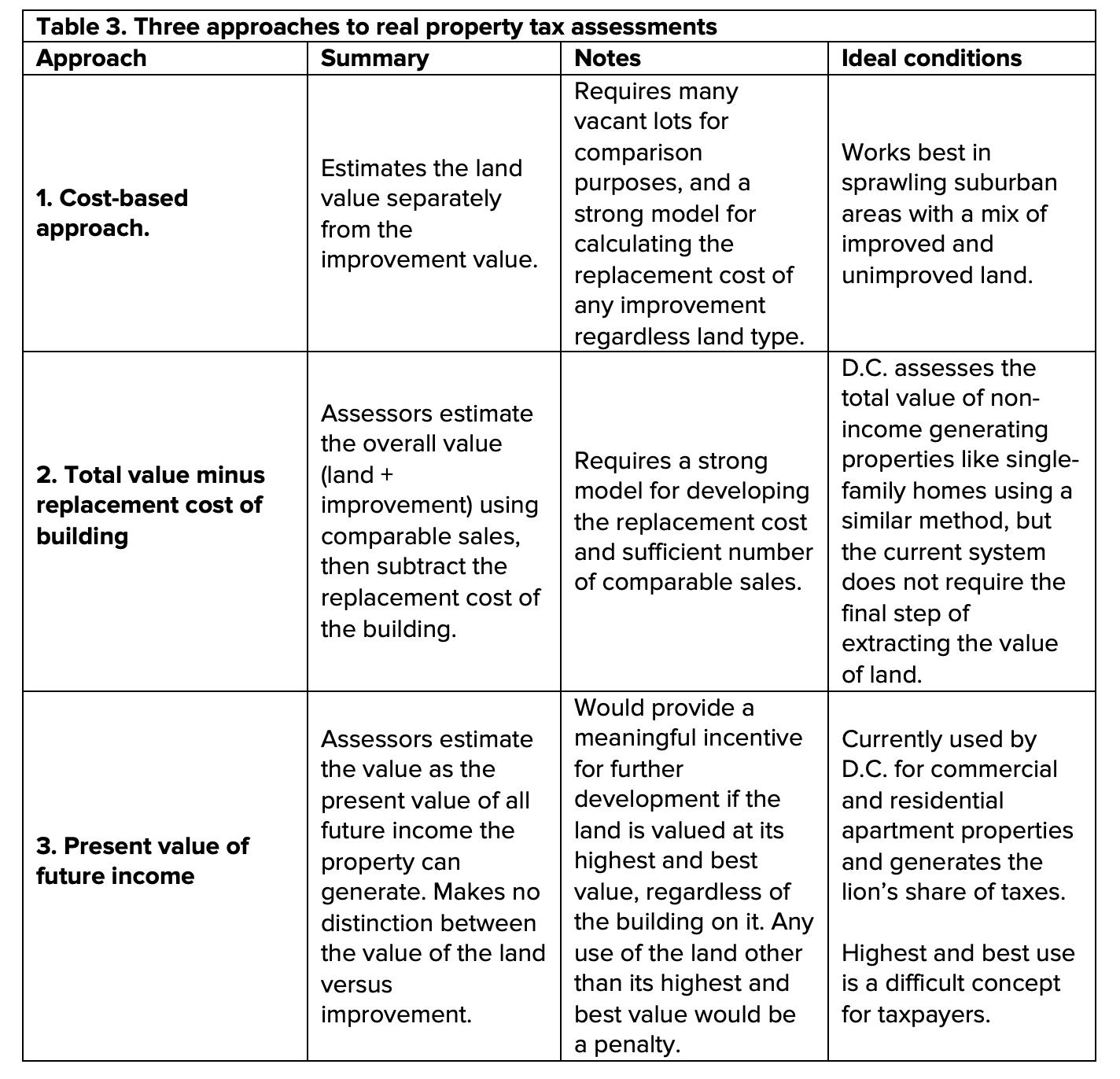

Broadly speaking, there are three main approaches to property valuation. [10] The first approach—the one most conducive to a land value tax—is the cost-based approach, which estimates the land value separately from the improvement value. Two things are necessary for this method. First, there must be a sufficient number of comparable vacant lots to correctly assess the value of the land independent of the type of improvement on it. Second, there must a strong model for calculating the replacement cost of any improvement regardless of the type of land it is on. This type of assessment works best in sprawling suburban areas since there is usually good mix of improved and unimproved land to develop reliable valuations. Furthermore, the types of improvements are relatively similar in nature, so costing out each component (roof, walls, doors, etc.) and adding them up to calculate the replacement cost generally provide consistent valuations.

Even in urban places like D.C. where there are few vacant lots, it is possible to develop reliable estimates of land values. This brings us to the second assessment approach, where assessors would estimate the overall value (land plus improvement) using comparable sales and subtract the replacement cost of the building to extract the land value. This method will be reliable if there is a strong model for developing the replacement cost and sufficient number of comparable sales. The District’s current tax assessment practice for non-income generating properties (largely single-family homes) is closest to this approach. The assessors use a mass appraisal system to assess the value of most single-family homes, relying on recently sold single family homes to calibrate the mass appraisal model that determines each property assessed value. (The city publishes an Assessment Ratio Report that document the values from comparable sales every year). However, the city’s real property tax regime does not require the final step of extracting land value from overall value.

The third method, always used for income-generating properties, is the trickiest to evaluate in the context of a land value tax. This approach to assessments values properties as if they were stocks or bonds: the assessed value is the present value of all future income the property can generate (sometimes called the Discounted Cash Flow Analysis). Assessors determine the net operating income from a property [11] and discount this value by a special kind of interest rate called the “capitalization” rate. [12] Valuations determined this way only focus on the economic use of the property; they make no distinction between the contribution of the land versus the improvement to this economic value.

Relatively fewer lots are assessed using the income approach, but these lots produce the lion’s share of valuations in the city. Almost all commercial buildings, investment properties, and residential apartment buildings are assessed this way. The income approach could provide an easy transition to a land value tax if the land is valued at its highest and best value, regardless of the building on it or what income it generates. But this would be confusing to taxpayers as it would mean the actual income generated by the property will not matter at all; the only relevant value would be what the property could generate if deployed in its highest and best use. At present, when assessors increase values of commercial properties when something nearby sells for a high price, property owners quickly object pointing out their legacy costs, government restrictions to income such as rent control, or the historic importance of the property.

Importantly, under current assessment practices, regardless of the approach, there is no real incentive to get the breakdown of value between land and improvements right. Assessors are only responsible for correctly assessing the overall value of the property. And D.C. law only allows owners to appeal to the overall value of property. Thus, while all property tax bills in the District separately report assessment values for the land and the improvement, this split might not reflect the fundamentals, but rather, the assessor’s conclusion based on limited market evidence.

If D.C. moves to a land value tax, these practices would have to be changed. Moving away from an income-based approach will likely create a lot of taxpayer confusion. And even though the tax bills split land value and the value of improvements, these reported values could change even when the total assessed values stay the same. Any reallocation of valuation between land and improvements will likely create great taxpayer angst and anger and will require additional resources for the extensive taxpayer education.

What, then, is a land value tax good for?

The analysis presented above shows that if the city were to adopt a land value tax in the context of its current restrictive land use practices, this new tax regime would be unlikely to increase the city’s housing supply. It would likely generate higher tax revenues from existing properties but would not act as an incentive for developing more intensively in large swaths in D.C. currently set aside for residential use.

Even within these limits, a land value tax could also prove useful: a property tax regime that taxes high value at a higher rate, specifically for low density development, could find greater political support for its adoption, putting the right amount of pressure on the city for a more permissive land use policy.

While transitioning to a land value tax could be hard because of assessment practices, this mental exercise of examining its potential impacts also informs us on a number of other policy actions the city can take to incentivize development in all parts of the city:

1. Further support the development of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs).

At present, zoning allows for ADUs by right, even in lots with the most restrictive land use. But the uptake appears to be slow largely because of limited financing options. The financing of an ADU is no different from the financing of renovating a bathroom: requiring either savings or to ability to borrow against savings. But what if landlords could build an ADU without additional tax penalty? This would open up lending in more favorable terms and whet homeowner appetite for ADUs, and could have the largest impact on increasing housing supply in lots where zoning is most restrictive.

2. Expand mixed use zoning and make it more permissive.

When zoning was last updated (a long process that began in 2007 and ended in 2016) the District has increased density along transportation corridors, but our analysis shows that current zoning is not permissive enough. The proposed changes to the Future Land Use Map are a start but could be made more rigorous. The adoption of more permissive zoning for mixed use zones—especially on large commercial lots which could mix commercial and residential use in the same building (beyond ground level retail)—could make a real difference in increasing the supply of housing units in D.C.

3. Rethink D.C.’s commercial tax structure.

At present, the District taxes commercial property at a rate higher than it taxes residential property. Importantly, rates increase by overall valuation. Commercial properties valued under $5 million pay a lower tax rate than properties valued between $5 and $10 million, which in return pay a lower tax rate than properties valued over $10 million. The analysis presented in this study shows that the greatest amount of room for redevelopment under current zoning is for commercial properties. However, the current tax structure creates a penalty for additional development in parts of the city that needs commercial improvement the most.

Editor’s note: This publication overlays tax use data from the D.C. Office of Tax and Revenue onto zoning maps for its analysis. Tax data categories do not fully align with zoning categories: institutional uses as designated in zoning may fall across various tax categories, including commercial or residential. Institutional land uses in zoning are often, but not always, tax-exempt. When originally published, the maps in this piece did not exclude tax-exempt uses from their commercial and/or residential designations. However, due to reader feedback, we have updated all maps in this piece to exclude tax-exempt commercial and tax-exempt residential uses, to better align with colloquial understandings of the terms ‘commercial’ and ‘residential.’

To learn more about the data and methods used in the analyses in this report, please see the Appendix.

Acknowledgments

Corey Holman provided data assistance by matching tax lots to zoning classifications. Sunaina Kathpalia provided research assistance. David Alpert, Yomi Omotoso, Fitzroy Lee, Maura Brophy, Alex Baca, Kathryn Zickuhr, and Jaime Fearer provided invaluable comments. Any errors in the analysis is in the sole responsibility of the author.