A new D.C. Policy Center report outlines the funding sources and expenditure patterns of subsidized[1] afterschool and summer programs in the District of Columbia: where funds originate, how they are spent, what capacity constraints providers experience, and how public and private stakeholders can help address those challenges.

The report was commissioned by United Way of the National Capital Area and received support from the District of Columbia Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education to fulfill the Office of Out of School Time Grants and Youth Outcomes Establishment Act of 2016 requirement to conduct a citywide Out-of-School Time needs assessment.

Continue reading the summary below or click here to access the full report.

Out-of-school time programs in D.C.

In 2016, an estimated 33,400 children and youth attended subsidized afterschool programs in the District of Columbia, and at least 15,000 children and youth participated in subsidized summer programs. These estimates are from a report the D.C. Policy Center published in October 2017, “Needs Assessment of Out-of-School Time Programs in the District of Columbia.” This report estimated the current capacity of subsidized OST programs, defined as those that receive funding from the federal government, D.C. government, or private foundations to provide structured afterschool and summer programming for children and youth from pre-K to 12th grade. It also estimated potential OST program needs under four different policy frameworks, and the corresponding gaps in supply.

In D.C., the landscape of subsidized OST programs includes those operated by public schools and public charter schools; those operated by other District government agencies, such as the Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR); and those operated by community-based organizations (CBOs) that receive public funding. In addition to these traditional OST programs, many older youth also participate in the Marion S. Barry Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP), operated by the Department of Employment Services (DOES).[2]

To ensure that subsidized OST capacity can effectively meet local families’ needs, it is necessary to understand how OST programs are funded, what costs OST providers face, how prices are structured for families, and how prices intersect with quality, content, hours, and other program characteristics. Therefore, this report surveys the fiscal landscape of subsidized OST programs,[3] reviewing the sources of funds (where OST programs get resources) and uses of funds (how OST programs spend money). In both these sections, the report provides detailed information on public funding and spending, and estimated revenue—including private revenue—and expenditure analysis for service providers. The report explores the potential fiscal needs of expanding OST programs, opportunities that are available to expand and better use existing funds, and the bottlenecks that might impair expansion efforts.

OST program funding sources: Where the money comes from

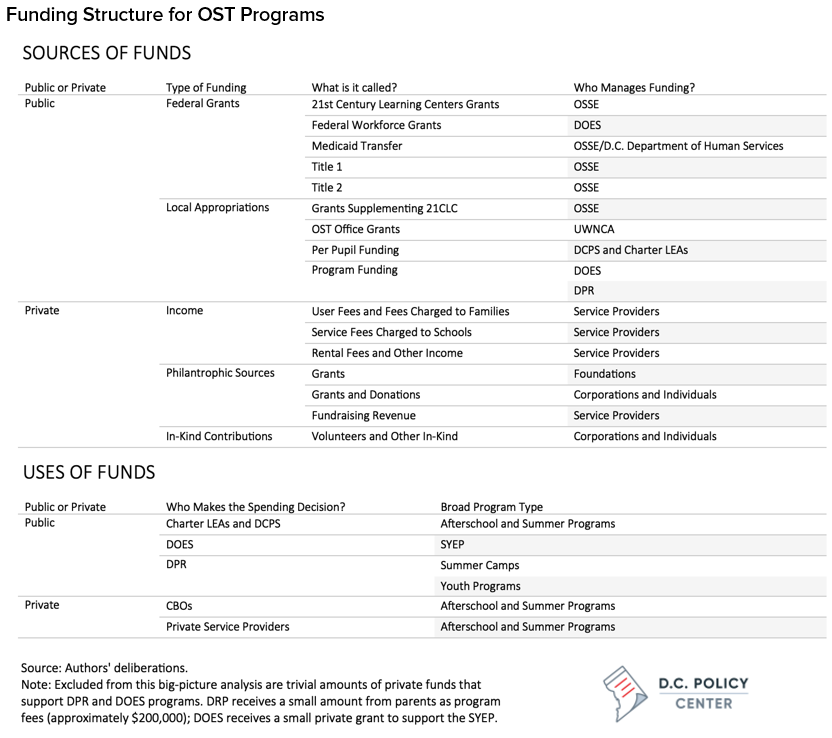

Subsidized OST programs in D.C.—whether operated by schools, specific government agencies, or by community-based providers—rely on both public and private funds to support operations.

Public (i.e., government) funds that support OST programs include federal grants and local appropriations, the latter paid for by revenue collected through D.C. taxes. The main source of federal funding for OST programs is the 21st Century Community Learning Centers (21CCLC) grant that support a large variety of organizations including DCPS, Charter Local Education Agency (LEAs), and CBOs. Additionally, Title I funds[4] that have not been spent during the academic year are also used to support DCPS summer programs.

Sources of private (i.e., non-government) funding include grants from philanthropic foundations, corporate sponsorships, individual donations, in-kind donations, program fees charged to families, and other resources. Almost every subsidized CBO provider relies on private funding to support operations, though the mix of the private funding varies greatly across providers. CBOs also receive in-kind support such as lent equipment, teaching materials, and volunteer time, which do not always appear on financial reports.

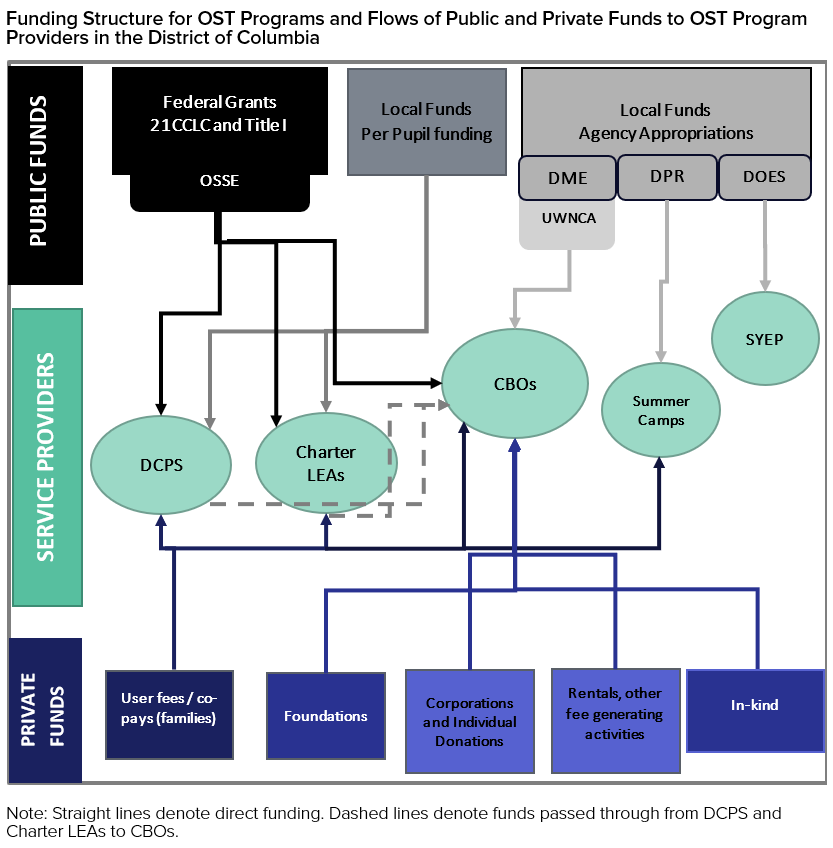

The chart below shows the flow of funds from public and private sources to different types of OST providers in D.C.

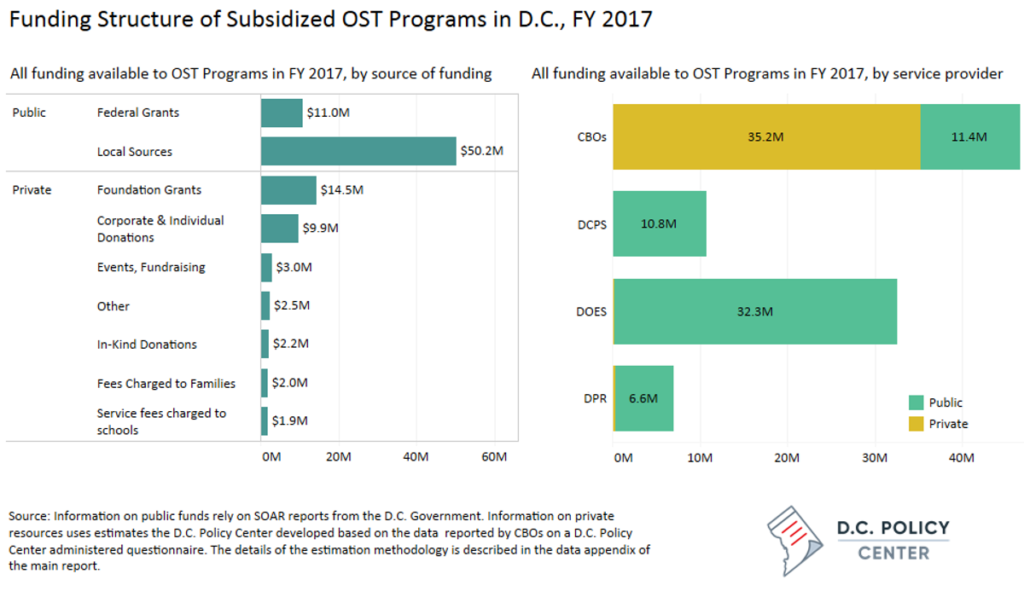

Data from FY 2017 show that in that year, the total amount of funding available for OST programs was over $97 million. Of this amount $66.2 million was from public resources—either District’s own revenue ($50.2 million) or from federal grants ($11 million). The remainder was largely raised from the private sector—from foundations (14.5 million), corporate and individual grants ($9.9 million), and other sorts of fundraising events held by service providers. The out-of-pocket expenses from families related to subsidized OST programs was roughly $2 million.

The headline figure of $97 million seems like a large amount, but it comes with caveats. First, this amount includes funds set aside for SYEP and some other youth workforce programs at DOES. We included these in our seat counts for capacity because they account for such a significant portion of the summer opportunities available to older youth in D.C., and they are also included in this fiscal analysis. But youth workforce programs or subsidized employment programs do not always fall under the traditional definition of OST programs.

For community-based-organizations, support from the D.C. Government and federal grants account for only about a quarter of total resources. These organizations raise $35.2 million each year from private sources. Not surprisingly, publicly provided programs at DCPS rely entirely on public funding. The only exception is the fees families pay to DPR for summer programs—the yellow shadow barely visible in the graph above, which stands for $400,000 revenue in fees families paid in FY 2017.

OST program expenditures: Where the money is spent

OST providers have expenditures for program-related costs such as personnel, supplies, and equipment, and overhead costs such as management of the organizations, financial management, fundraising activities, or technical needs such as computer systems. Programs must also pay for space, unless provided by a school or other organization, and may also need to pay for transportation depending on the needs of the program.

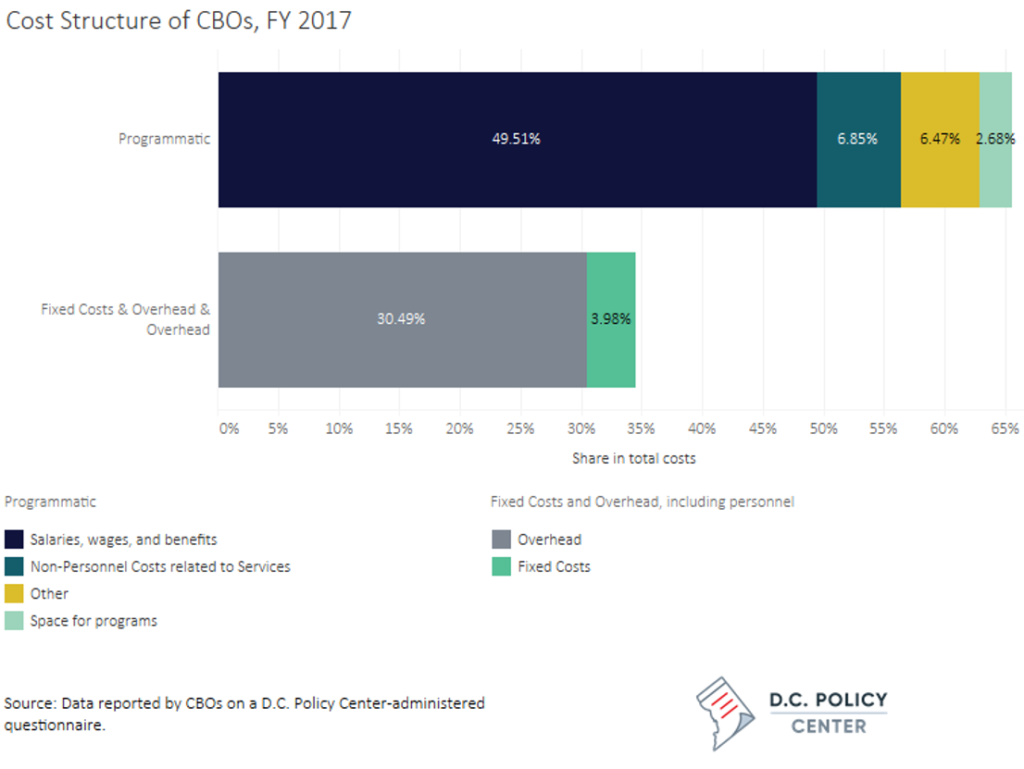

Our analysis divides OST program expenditures into two main categories: programmatic expenditures and overhead.

- Programmatic expenditures include any type of spending that is directly related to the provision of programming, such as wages for instructors, meals for participants, or the educational materials and supplies used in class.

- The other type of spending is non-programmatic expenditures—often called overhead—which include money spent on things that indirectly support OST programs, and which support broader organizational operations. This might include senior staff members and administrative staff members who manage these programs, accounting services, fundraising efforts, or marketing staff. It also includes fixed costs that are costs that are hard to adjust in the short term, which might include the cost of space, and utilities, security and maintenance services for the building, or insurance.

Expenditure patterns among OST program providers in D.C. vary dramatically, by size of organization, age of participants, type of program, service location, and other factors. Importantly, budget structures are very different at the D.C. Government agencies and CBOs, largely reflecting the scale of the D.C. Government.

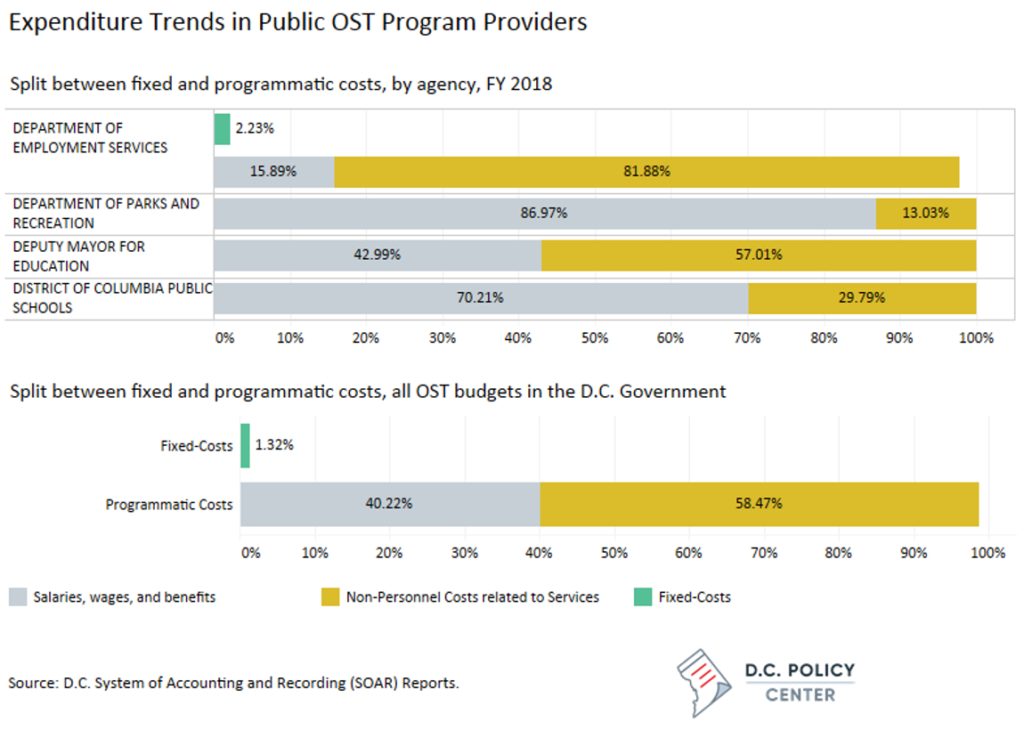

Expenditure patterns in government-operated programs

Overhead expenditures for government-operated OST programs are generally very low in D.C., because most of these programs do not have to pay for space, which can be very costly. Secondly, the D.C. government handles a number of traditional overhead costs through other departments. For example, D.C. government-operated programs may utilize human resources functions, legal services, and financial services provided by the Department of Human Resources and the Office of the Chief Financial Officer, and these expenditures are accounted for in the budgets of those respective entities instead of DPR, DOES, or DCPS’s balance sheet. And even when human resources or financial operations personnel are included in the OST-providing agency’s budget, the agencies still benefit from other centralized systems, such as the D.C. government’s centralized accounting system and payroll system. The use of these centralized services can therefore help keep overhead costs low for government providers.

Still, even within government-provided programs, the structure of expenditures for workforce programs like SYEP is very different than OST program provided at schools or summer camps, as subsidized youth workforce programs in D.C. spend approximately 85 percent of funds on stipends or wage subsidies for participants. The remainder supports overhead and contractual services, some of which are related to program content, and others related to the cost of renting space or providing security.

Expenditures at non-government providers (community-based organizations)

CBOs also report different cost patterns compared with agency- or school-provided programs. First, the overhead costs at CBOs in D.C. are much higher on average compared to the afterschool and summer programs provided by DCPS. The estimated share of overhead costs across all CBOs for which we have information is approximately 34 percent. While administrative personnel accounts for most of these funds, the cost of space for CBOs is sometimes substantial. Data from CBOs suggest that the biggest determinant of space costs is whether an organization delivers services on school property or at some other location; among those that have access to school property, only 6 percent of costs are associated with space, compared to 25 percent among CBOs that do not have access to school space. Discussed later in this section are the impacts that CBOs must report to meet the requirements imposed by grant rules or donor wishes, which often include restrictions on what the funds could be used to pay for or where they could be spent.

Challenges faced by OST program providers

In addition to analyzing revenue and expenditure trends, the report also explores challenges faced by OST providers and other stakeholders. It is clear that present public and private funding levels do not allow providers to meet the current demand or need: Affordable or free programs generally report long wait lists, and parents and caregivers often must piece together multiple forms of care to cover children’s afterschool and summer hours.[5] Therefore, in addition to an overall analysis of revenue sources and operating expenditures, the D.C. Policy Center also examined where funding limitations created pressures to meet costs or expand scale.

To identify and understand these constraints, the D.C. Policy Center solicited input from CBOs and OST program providers and conducted in-depth conversations with several OST program stakeholders. In this process, CBOs identified significant constraints to growing capacity in the following areas: challenges in expanding administrative capacity; revenue constraints; fluctuating expenditure trends; programmatic staffing capacity and stability; inability to secure more space due to rising costs; and matching specialized programs with participants. Each of these issues is discussed at greater length in the report.

Challenges at programs operated by the D.C. government

Current public and philanthropic funding levels appear to be the biggest constraint preventing most nonprofit and government-operated OST program providers from serving more children and youth. Public funding appeared to be less of a constraint for organizations that have relied exclusively on program fees, or for some small providers based in much larger organizations. Consistent funding was also an issue; though many private and government grants are for multiple years, there are few alternative sources of funding if a funder’s priorities change and they decide to move away from funding OST programs, making long-term planning difficult.

Challenges at programs provided by community-based organizations

Several CBOs reported that securing funding for administration and overhead was difficult, and they face strong pressures (including grant requirements) to keep their overhead funding ratios low. While some CBOs have access to administrative services as an in-kind donation from a larger partner organization, relatively few funders offer to pay for areas like development, security, or communications. However, CBOs noted that they still need to be able to invest in these functions to operate effectively and to maintain or grow their OST program capacity, especially given the substantial recording-keeping and reporting required by many public and private funders.

Expanding administrative capacity

Several CBOs reported that securing funding for administration and overhead was difficult, and they face strong pressures (including grant requirements) to keep their overhead funding ratios low. While some CBOs have access to administrative services as an in-kind donation from a larger partner organization, relatively few funders offer to pay for areas like development, security, or communications. However, CBOs noted that they still need to be able to invest in these functions to operate effectively and to maintain or grow their OST program capacity, especially given the substantial recording-keeping and reporting required by many public and private funders.

Even when donors are willing to fund overhead costs, these functions may not scale smoothly for very small organizations, hindering their attempts to increase capacity. For example, if a very small organization has only one staff member focused on administrative functions, bringing an additional full-time staff member on to this role would then result in a doubling of administrative staffing costs. Centralized, shared administrative resources may therefore be one avenue for helping smaller organizations operate more efficiently, seek more funding, and meet reporting requirements more easily. Very small organizations may also operate more efficiently if merged into a larger organization, although many have been operating independently for decades and may not wish to or be able to overhaul their organization in this way.[6]

Addressing revenue constraints and smoothing expenditure trends

Current public and philanthropic funding levels appear to be the biggest constraint preventing most nonprofit and government-operated OST program providers from serving more children and youth. Public funding appeared to be less of a constraint for organizations that have relied exclusively on program fees, or for some small providers based in much larger organizations. Consistent funding was also an issue; though many private and government grants are for multiple years, there are few alternative sources of funding if a funder’s priorities change and they decide to move away from funding OST programs, making long-term planning difficult.

Expanding staffing capacity and stability

Staffing that requires specialized training was frequently identified as a potential bottleneck for increasing future capacity. Due to the nature of OST programs, particularly afterschool programs, demand is concentrated at a particular time of day, when skilled staffing often comes from a limited pool of candidates. It can be especially hard for programs to attract consistent skilled staff at current pay levels, particularly if those positions are part-time and require varying or nontraditional hours.

Concerns about staffing as a scaling constraint apply to government-operated programs as well as CBOs. For example, efforts to expand DCPS After School capacity could likewise be limited by the challenges of recruiting DCPS teachers to staff the academic enrichment portion of the afternoon,[7] as there is a limited number of DCPS teachers available at each school from which to recruit.[8]

Addressing space constraints

Space was often—but not always—a challenge for CBOs. Very small organizations which do not own space may face rising rents as well as funding restrictions on overhead. Even for providers for whom space was not an immediate concern, such as those who owned their space or who had long-standing arrangements to use donated space, space could be a limiting factor for future expansion.

Matching specialized programs with target populations

There are barriers beyond capacity. A singular focus on capacity, without funding dedicated to reduce other barriers, such as funding transportation or helping providers locate closer to their target communities, may leave some communities unserved or underserved. Many CBO providers, especially smaller providers, serve specific populations, such as low-income children or youth in a specific geographical area. Many of the barriers identified by families and participants in the 2017 needs assessment, such as transportation and caregivers’ work schedules, may prevent families from taking advantage of programs that would be best targeted toward their children’s needs and interests.

Recommendations to expand capacity

Expanding the capacity of high-quality, affordable OST programs in D.C. will require both more resources and more efficient use of the resources that are currently available. Decisionmakers in the D.C. government and at private foundations should not only consider what optimal funding levels would look like, but whether current funding streams as well as existing OST programs could be managed in a different way to increase utilization and reduce per slot costs, and whether additional collaboration and coordination among donors or program providers can achieve such cost savings. There may also be opportunities to more effectively leverage federal and local funding to increase private commitments, reallocate funding across different public programs, or shift some costs to families who can afford to pay.

This report’s findings point to five overarching recommendations for the Commission on Out of School Time Grants and Youth Outcomes, which are discussed in greater detail in the report:

1. Improve data collection and analysis to identify funding trends and gaps: Currently available data on funding sources and uses are scattered and decentralized, collected across different agencies and funding entities. The increased support for OST programs through the DME’s OST Office provides an opportunity to centralize service provider information. One potential approach is the development of a common document or spreadsheet template to streamline the data collection and reporting process for funders and providers, both public and private. For local government expenditures, a budget code for OST funding might also help streamline data collection and analysis, especially for examining trends over time.

2. Increase funding and revenue stability for OST providers through better coordination between decisionmakers on public and private sources of funding: Public and private funding priorities can shift and diverge over time, and on different schedules. These shifts may leave significant gaps in providers’ capabilities, especially if these gaps include support for non-programmatic operations, which providers need in order to invest in their quality and capacity over time. Therefore, increased coordination between foundations and D.C. government agencies will be vital to identifying and addressing gaps going forward.

3. Find opportunities to help funders and providers share resources and build administrative capacity: Smaller providers must spend a larger share of their limited resources on overhead, which limits the resources that can be directed towards providing OST programs and additionally limits their potential to expand their capacity. Funders can help them scale their efforts by providing more support for overhead expenditures. This may require a combination of adopting more flexible allowances for overhead rates in grant agreements, and helping providers share space, staff, and resources to operate more efficiently.

4. Balance organizational efficiency with families’ needs: The high costs associated with renting or owning a program space present a challenge for OST providers who want to locate in high-demand areas, which may lead providers to locate in areas farther away from families who would most benefit from their programs. Improving transportation options to, from, and between programs may be one way to address this issue; co-locating several programs targeting different age groups at a single campus may be an alternative.

5. Address providers’ needs for skilled or certified staff: Many CBOs reported that finding more skilled or certified staff is a challenge as they expand capacity, especially for part-time staff. Increased funding and compensation for skilled staff may be one way to increase availability. It may also be possible for providers with complementary schedules to share staff to afford these instructors more hours and pay.

Click here to read the full report (PDF).

About this report

This report received support from the District of Columbia Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education to fulfill the Office of Out of School Time Grants and Youth Outcomes Establishment Act of 2016 requirement to conduct a citywide Out-of-School Time needs assessment. United Way of the National Capital Area commissioned the report.

About the data

This report uses data from government data sources, publicly available information, and surveys of CBOs. These include:

- SOAR reports on uses and sources of government funds for fiscal years 2015 through 2018 obtained from the D.C Office of Budget and Planning (OBP).

- Budget books for fiscal years 2015 through 2019 published by the D.C. Office of Chief Financial Officer (OCFO).

- Funding information on “Summer Strong” grant recipients provided by the DME.

- Detailed funding information collected through a survey of OST program providers.

The report also incorporates some information from interviews the research team conducted with government agencies, foundations, and service providers. For detailed information on how the funding and cost estimates were developed, as well as more information on the data sources used, please see Appendix A. Data Sources and Methods (PDF).