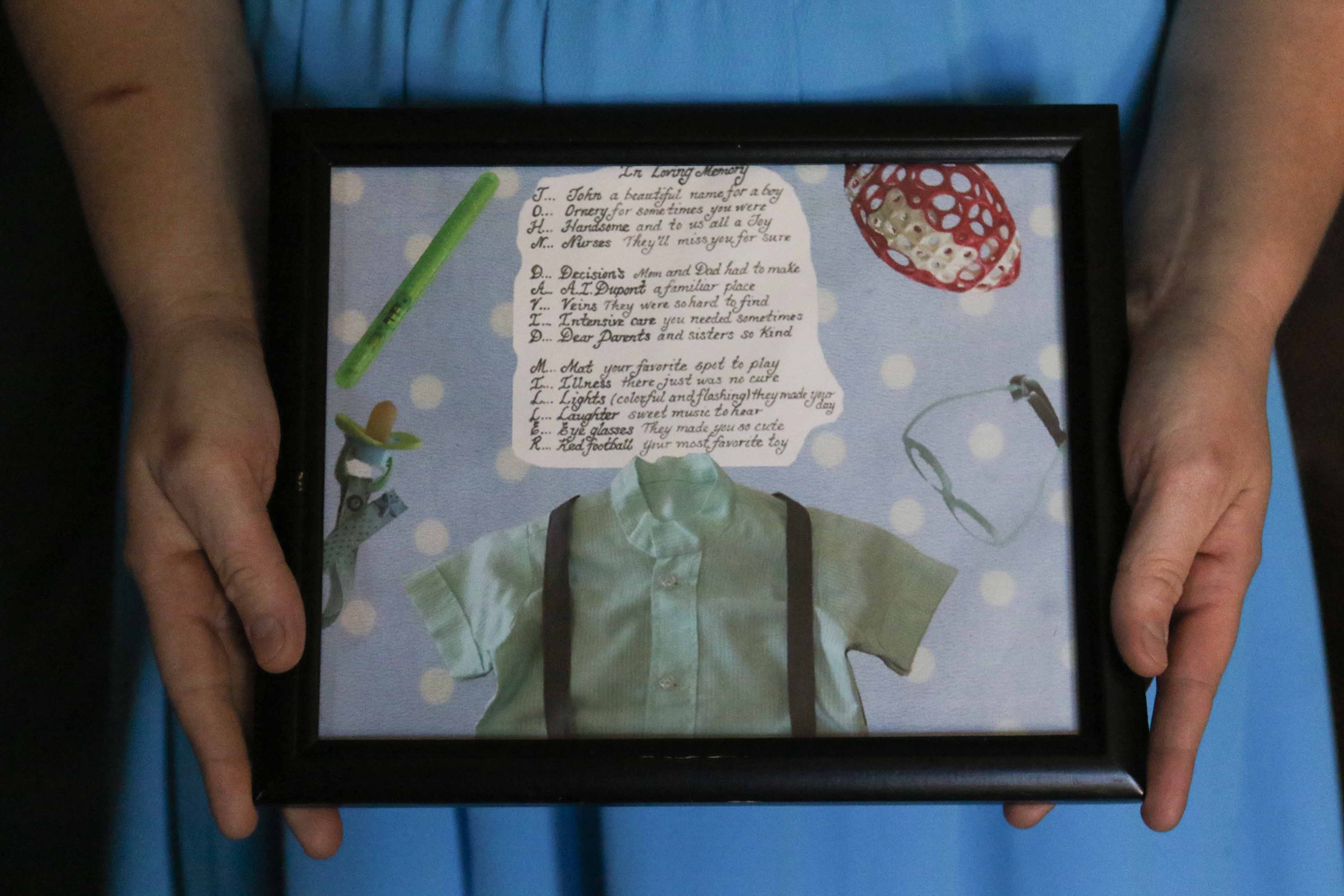

A memorial to John David sits outside Laura and Toby Miller’s bedroom door.

His crib.

In it are the yellow flyswatter and red mini-football that were his favorite toys. A traditional Amish outfit — turquoise shirt, black pants and suspenders — is laid out on the mattress.

A wind chime with John David’s name etched on it sings in the breeze outside the family’s front door, a gift from Nemours doctors and nurses.

Laura and Toby don’t yet have a tombstone for their son’s grave. But make no mistake, John David is in almost every room of this Dover home.

It’s four months since John David’s January 2015 death when the Millers receive a handwritten letter from the Clinic for Special Children. A geneticist expresses her condolences and writes that she might have some insight into what killed their son.

When the Millers are ready, she’d like to talk to them.

Weeks later, Laura and Toby, accompanied by their Uncle Ervin and Aunt Betsy, make the trip to Strasburg, Pennsylvania, to hear the news.

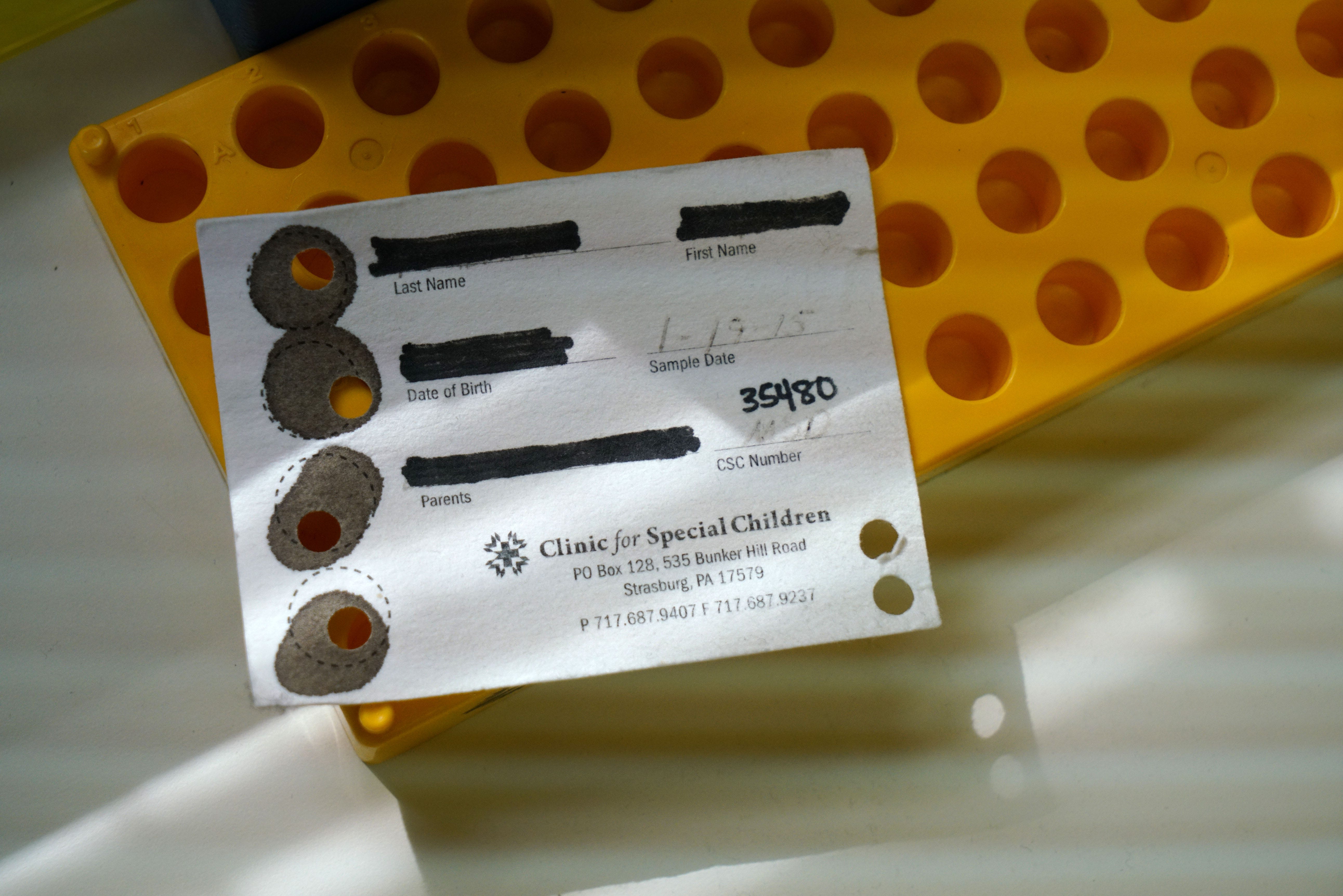

Months before John David died at the age of 25 months, the family had taken him to the clinic for genetic testing, hoping doctors would find a mutation to explain the toddler’s failing health.

But researchers didn’t know what they were looking for. And the chance of finding a single mutation is like trying to find one misspelled word in a lengthy novel.

After several months, geneticists narrowed John David’s disease to three mutations. Thanks to preserved tissue samples of his cousins Carolyn and Martha Ann — who died in 1997 and 2005 — doctors found all three Miller babies shared the same mutation, called YARS, after the gene involved.

This mutation prevented their bodies from correctly building proteins, affecting the function of all of their organs.

Some in the Amish community thought the Miller families put their babies through too much — too much testing, too much medication, too much time in the hospital.

Nothing the doctors tried could save Carolyn or Martha Ann or John David.

But could it save cousin Grace?

Baby Grace has spent the first four months of her life in the intensive care unit at Nemours/A.I. duPont Hospital for Children. Born nine weeks premature, she needs round-the-clock care.

It’s here that doctors notice she isn’t gaining weight or developing as expected. To figure out what’s wrong, Grace needs to undergo genetic testing. As Thelma signs the consent papers at the hospital, she sees the word “YARS” on the form.

Is this one of the genetic mutations they were testing for?

The doctors nod.

Thelma’s stomach drops. She knows instantly her daughter has the same disease that killed other Amish babies. A phone call a few weeks later confirms it.

Grace is the fifth baby in the Miller family — and only the seventh in the country — to be diagnosed with a disease now called YARSopathy. Her cousin Mary Beth was diagnosed a few months earlier.

When it’s time for Thelma and Buddy to take Grace home, Thelma is overwhelmed, remembering what Laura went through with John David. Constant care. Memorizing dosages of as many as 16 medications at one time. Very little sleep.

But her experience with Grace is different, partly because Nemours doctors feel more confident about taking a wait-and-see attitude. There is no rushing to the emergency room, no stays in the intensive care unit. Grace does have surgery for a feeding tube. Slowly, she begins to gain weight.

The baby soon starts physical therapy. Therapist Cindy Burritt realizes Grace is strong-willed as she works with her to become comfortable lying on her tummy.

While Thelma sees Grace developing more than John David did as an infant, it’s still unclear how much time her daughter has.

It’s early 2017, Nemours doctors believe children with YARS likely won’t live beyond their second birthday.

That’s about to change.

Grace is transfixed by the Apple Watch.

She’s 16 months old now, and her narrow eyes stare at the black screen as gray text message bubbles pop up. She reaches out with her pointer finger to tap the black screen.

She’s oblivious to the adults around her. They are talking about how her eyes seem more steady, how her belly seems chubbier — a result of her gaining 2 pounds.

This is all good, Dr. Matt Demczko tells her mother, Thelma. Really good.

Grace and her mother are here, at the Nemours’ Kinder Clinic in Dover, on this warm February 2018 day for a regular checkup.

The toddler, dressed only in a diaper, is still focused on the watch when her physical therapist lifts Grace from her lap and onto the exam table. Grace tucks in her knees and rolls.

“Holy smokes,” Demczko blurts out. “I’m getting teary eyed. I never saw her do that before.”

Rolling over. A milestone most babies hit around 4 to 6 months. Some of Grace's cousins never hit this milestone. They never heard their mothers’ voices; they never took their own steps. They died by age 2.

Small moments such as these matter to Demczko and Thelma.

“I’m over the moon,” Demczko says.

Thelma's response isn’t about her own daughter.

“We wouldn’t know anything without John David,” she says.

The perfect medical home

Nemours doctors have long wanted to create the “perfect medical home.” A place where a team of doctors provide patients the best kind of primary care, yet the cost is as inexpensive as possible to patients’ families.

Two years ago, they realized the Amish are the key to learning how to build it.

For years, the hospital has worked with the Clinic for Special Children, which has cared for sick Amish and Mennonite children in Lancaster County for three decades.

In that time, this small clinic has learned to look at a child’s genetics when providing care, in some cases giving children better lives by preventing them from needing a wheelchair or suffering from severe brain trauma.

This kind of care, which the clinic offers at low costs, is expected to be the future of medicine. It's often called precision medicine.

Because Plain communities are so insular, the genetic diseases seen in the Amish of Lancaster County aren’t typically seen in the Dover Amish. It’s also often a challenge for Delaware families to travel to Strasburg because it's more than two hours away.

Nemours saw an opportunity: They wanted to emulate the work of the Clinic for Special Children, as well as increase their reach in Dover. Fortunately, the hospital had the physical space.

In August of 2017, the Nemours Kinder Clinic opened in Dover. The space also serves non-Amish patients, with separate waiting and exam rooms for the Amish. Wood accents frame the walls, which are dotted with paintings of the countryside and farm animals.

Dr. Jay Greenspan, the chair of the pediatrics department at Nemours, hopes to apply the clinic model of medicine to all children in Delaware.

“My dream of where this is going is we take this model in Dover and use it as a way to say, ‘Look, we can save a lot of money and heartache by understanding the genetics,’” he says. “If you mapped out Delaware, there’s less than a million people.

“You can use Delaware to become the next step for the medical home.”

Medicine, in a whole new light

Enter Drs. Michael Fox and Matt Demczko.

They are college buddies. Both graduated from Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster County. They grew up in central Pennsylvania. During their undergrad, both spent time at the Clinic for Special Children.

Demczko, who became a chief resident at Nemours, is one of the young doctors who helped treat John David Miller during the child’s last month. The experience helped open his eyes to the kind of medicine he wanted to practice: helping medically complex children.

Nemours asks Demczko to run the Dover clinic shortly after he completed his residency. Demczko suggests his good friend Mike join him.

Both Fox and Demczko spend six months, at different times, at the Clinic for Special Children in unofficial fellowships. Under medical director Dr. Kevin Strauss, they learn how to care for Amish and Mennonite families. Nemours rents a house for them, so they can be embedded in the community.

“It was one of those experiences that changes you as a physician, I think,” Demczko says. “It makes you see medicine in a whole different light.”

A discovery and a new sense of hope

After its official founding, Nemours joins the Plain Community Health Consortium. The members include the Clinic for Special Children and similar clinics from Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin.

Every quarter, the doctors meet via conference call to share cases that they are having difficulty diagnosing. In spring 2017, Dr. Olivia Wenger, medical director of the New Leaf Center in Ohio, presents a case that has puzzled her for years.

Her patient, a 5-year-old Amish girl, has kidney problems, developmental delays and early-stage liver failure. She has seen specialists throughout Ohio and at the Mayo Clinic. She has undergone millions of dollars of genetic testing — yet no one can pinpoint a diagnosis.

As the Ohio doctor began listing her patient’s symptoms, Fox and Dr. Katie Williams, then a geneticist at the Clinic for Special Children, look at each other and mouth the words:

“This is YARS.”

Almost immediately, the girl’s blood sample is sent to the Clinic for Special Children.

Two days later, the geneticist confirms the 5-year-old has YARS. The test cost $50.

The Ohio girl is the oldest known living person in the country with this disease. She can walk and talk. She’s learning numbers and letters. She has cochlear implants and shares physical features, such as deep-set eyes, with Grace and Mary Beth, the other Delaware child with YARS.

When Fox and Demczko tell Grace and MaryBeth’s parents about the girl, tears well in Thelma’s and Mary’s eyes.

Both mothers expected months, not years, with their daughters.

After meeting with the doctors, Mary — curious about the genetic links between Delaware and Ohio — collects church directories and family histories that detail information about members and their children.

On scratch paper, she maps a family tree and shows how the children with YARS are related.

Fox says it takes genetic counselors years to learn how to do this correctly.

Doctors still use Mary’s family tree in their research.

Thelma and her husband, Buddy, meet the Ohio girl a few months later when they are nearby for a family reunion. Thelma is struck by how much she looks like an older version of Grace, complete with a halo of gold hair.

“It gave me a lot of hope,” she says, “that Grace has a chance for a normal life.”

When less, is more

In Thelma and Buddy’s Dover home, just above Grace’s pink polka dot changing table, hangs a name verse poem Thelma wrote in honor of John David. It’s the same one Toby and Laura have in their home.

From the beginning of her life, Grace has a distinct advantage over John David. She is diagnosed much earlier, at a time when doctors have a better understanding of how patients’ bodies adapt to the changes the mutation causes.

John David’s lab tests caused such concern for his doctors they felt they had to keep intervening medically, Demczko says.

But it turned into a “Whack-a-mole” situation. When doctors tried to fix something for John David, another serious condition would present itself.

With Grace, the doctors stop aggressively intervening. Instead, they cautiously monitor her. So far, it’s working well to spare her the agony and cost of aggressive treatment, and she’s developing more than John David.

When he was alive, the toddler was hospitalized 14 times. Together, Grace and cousin Mary Beth are hospitalized four times. John David underwent five surgeries; the girls undergo surgeries for a feeding tube and cochlear implants.

John David needed 29 infusions. Grace has not had one.

“Somehow their bodies learn to manage it,” Demczko says. “And it does its best when we kind of take a step back and keep our hands off.”

One example: John David received regular infusions of albumin, a protein the liver produces, because his levels were about 50 percent lower than normal.

With Grace, doctors accept that her albumin levels are always going to be low. Instead of giving her an infusion, which didn’t help John David, they monitor her instead.

“Who’s to say John David’s experience will be the same for Grace and Marybeth?” Fox says.

Maybe it will be like the Ohio girl’s, he says.

“Or maybe even better.”

When Thelma was pregnant with her first child, doctors told her there was no chance for her unborn baby.

It was 2006 and doctors told the then-21-year-old, who was nearing the end of her second trimester, that her unborn baby was underdeveloped. Its head was at 23 weeks, its body at 25 weeks. The baby would not be alive at birth, doctors said.

About 10 weeks later, Thelma went into labor in her home. She prepared herself to cradle a silent baby. But when Joanna was born, she was pink. She instantly began to cry.

Thelma and her husband, Buddy, got 16 months with their Joanna before she died of complications related to primordial dwarfism. Looking back, Thelma feels she was ignored by the doctors, that her voice as Joanna’s mother didn’t matter.

With Grace, things would be different, Thelma decides when she’s born.

Demzcko and Fox attribute many of Grace’s milestones to Thelma.

The mother of four — all of whom are under age 8 — reads any book she can get her hands on that details how the body works and the impact nutrition can have on one’s health. Maybe something in there can help Grace, she thinks.

When Grace has severe acid reflux, doctors prescribe her different medications. Yet it doesn't go away. Thelma thinks there might be another option and calls a cousin who works with babies with reflux. The cousin recommends a probiotic.

Thelma tries it for Grace, and not long after, the reflux goes away. Although there’s no medical research involving this probiotic, the doctors recognize it has helped Grace. They are open to Thelma trying homeopathic methods.

Before Grace underwent surgery for cochlear implants, Thelma prepares to learn sign language and teach it to Grace and her children. She plans to give her daughter a sign name — used to identify a person — that translates to “determined.”

When the Millers go on family outings or attend church, Thelma props Grace on her hip or pulls her in a wagon.

Leaving Grace behind is not an option, even though Thelma admits there are times when it’s easier. She wants Grace to experience normal life — to hear music and partake in conversations the best she can.

Getting there comes with immense challenges. Grace sometimes has crying fits, overwhelmed with the new sounds she can hear from the cochlear implants.

But Thelma will not turn them off.

“It’s going to be rewarding in the long run,” she says. “That’s why I stick to it. Because it’s not fun to make your baby fussy if she would be happy otherwise.”

She pauses.

“I have to tell myself it’s going to be worth it in the long run.”

Doctors fear YARSopathy isn’t the only fatal genetic disease among the Dover Amish.

The Nemours doctors want to know what they and the community are up against. In order to do this, they need to collect Amish families’ DNA to study. A grant of $80,000 has helped kickstart the research.

Erin Crowgey, research associate director of bioinformatics at Nemours, has developed a DNA test that will screen for 1,300 genetic mutations. Nemours researchers hope every U.S. clinic that treats the Amish will one day use this test on newborns, their parents and even young couples who don’t yet have children.

“We’re trying to better say, ‘Oh, you are a carrier for this rare disorder. That’s great that you’re going to deliver your baby with a midwife at home. But you need to be prepared for the fact that he might have this very toxic disorder,” Crowgey says. “If they aren’t seen really quickly, your medical costs are going to be astronomical.

“You’re going to have a different course of life,” she says.

The kind of testing is not just for the Amish: In the past decade, there has been a boom in genomic medicine. At Nemours, researchers use the same technology to help children with cancer.

But this kind of genetic testing is easier to do with the Amish, Fox says. The community has a “closed population,” meaning there are certain genetic problems they know exist only within the group — and dozens and dozens they can rule out.

Because geneticists know what to look for with the Amish, they can complete a test in a matter of hours.

That’s not yet possible for most people, Fox says. But the day will come, he says, when people will not talk about the symptoms of an illness, but its genetic basis.

Though it’s still unclear how interested Amish families, especially young couples who don’t have children, will be in genetic testing.

Donald Kraybill, a professor at Elizabethtown College and a leading expert in the Amish culture, says many in the community have started to accept modern health care, including genetic testing.

“The Amish, on one hand, appear to be conservative and traditional,” Kraybill says. “On the other hand, they are quietly open to science.

“It’s remarkable.”

In the years following the death of John David, parents Toby and Laura have become two of the Kinder Clinic’s biggest advocates. They sit on its board and are the first people Nemours doctors call when they have a question about Amish culture.

But in late November, it’s eight of 11 Dover Amish bishops that Demczko and Fox meet with. In the Amish schoolhouse, next to the cemetery where John David, Martha Ann and Joanna are buried, the doctors explain their hope for genetic testing.

The elders recommend Nemours conduct the testing a day or two before church services if it's OK with the community member hosting the Sunday service in their home.

Not everyone in the community will want genetic testing, the bishops warn the doctors.

That’s fine to Demczko and Fox. It’s a start.

Laura and Toby had their four daughters tested when John David was at the Clinic for Special Children. Their youngest son had not been born then.

“Before all of this happened, I would have said no,” Toby says. “I would have pushed it away.”

Three of the four girls are carriers. The family doesn’t know which ones, at least right now.

“Once they get older, they can make that choice for themselves,” Laura says. “I don’t want that weighing on their minds as they’re growing up.

“Because they were old enough. They saw firsthand.”

“Careful,” Thelma says, looking down at Grace in her pale blue dress and tall gray socks. “You’re going too fast.”

Now 26 months, the toddler has just slid to the tile hospital floor. Almost instantly, she pops back up and continues taking small, teetering steps down a hallway off the Nemours lobby.

Thelma holds her hand. Walking is Grace’s favorite thing to do, she says.

In the past six months, Grace has hit two milestones: She’s taken her first steps and recognized her mother’s voice. Her face is more animated. She babbles. She belly laughs. She’s breaking into Thelma’s kitchen cabinets, forcing mom to baby-proof.

While Grace has never stayed at Nemours for long periods, she’s at the hospital every Monday for hourlong speech therapy appointments.

Thelma and her family recently spent Thanksgiving with John David's family.

Whenever the Millers are together, Thelma often notices how Toby’s and Laura’s faces light up when they see Grace.

Thelma once asked Toby if it was hard for him to see Grace, to see how well she is doing. John David could be this far along if doctors had known everything, she tells him.

Toby’s reply: It makes everything John David went through worth it.

Even though Grace has lived longer than John David and Carolyn and Martha Ann, doctors are still unsure of her life expectancy.

Her disease is still considered lethal.

But one day, maybe soon, Nemours doctors and therapists hope she will say her first few words. Thelma has a different goal in mind.

She just wants her daughter to recognize the sound of her own name.

Grace.

About this project

“Saving Grace” is based on hours of interviews with Amish families, doctors, nurses, geneticists and Antabaptist experts over the course of a year. Many of these scenes were re-created through interviews, while others were observed by the reporter and photographer. The Amish families welcomed us into their homes and to doctor appointments. They asked that no photos be taken of their faces, due to their religious belief and Delaware Online respected their wishes.

About the reporter

Meredith Newman is the health reporter for Delaware Online. She previously worked for The Capital, the newspaper in Annapolis. She graduated from Syracuse University.

About the photographer

Jennifer Corbett is a staff photographer for Delaware Online. For over 20 years, her photos have taken a deeper look into issues that affect Delawareans’ everyday lives. She has worked on several long-term projects, including ones focusing on the opioid epidemic and autism community.