Prime minister Narendra Modi’s `75,000 crore income top-up for small and marginal farmers is not, in the truest sense of the term, a Universal Basic Income (UBI), but it has revived interest in UBI or, in the context of making it affordable, a modified UBI for the bottom 20 or 30% of the population.

Many have argued that a UBI, or even a modified UBI which promises a reasonable sum of money, is unaffordable and that it has unfortunate side effects in terms of the money being squandered, for instance. Going by the results of the Sewa Bharat-INBI pilot in Madhya Pradesh in 2012-13, and a follow up of it five years after it was over, suggests this may not be correct.

Sewa-INBI took up two types of villages in Madhya Pradesh for their pilot, one was a normal Indian village while the second was only inhabited by tribals. In each case, a set of ‘control’ villages was identified where no UBI was given while the other set got a UBI for 12 to 17 months. Over 6,000 people got the UBI of `200 per adult and `100 per child; after a year, this was raised to `300 and `150—respectively—in the normal villages. In the tribal villages, the sum was kept at `300 and `150 in the 12-month period.

Since the pilot was done in the pre-Modi period of 2012-13, there was no government-induced push to PSU banks to open Jan Dhan Yojana accounts for people. Even at that point, however, 70% of the women in the UBI villages said they had no problem opening a bank account as compared to 44% in non-UBI or ‘control’ villages. Similarly, while 61% of households in non-UBI villages said they faced considerable difficulty in withdrawing their money, only 27% in UBI villages faced difficulties.

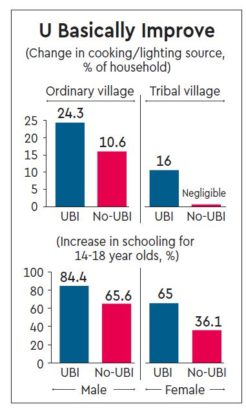

And, though this was prior to the Swachh Bharat days, about 16% of the households in the UBI villages said they had made changes to their toilets by the end of the project, compared to only 10% in the control villages; amongst the households that had no toilet at the outset in the general pilot, more than 7% reported building a new toilet as compared to 4% in the control villages. Also, 24 of the UBI households had changed their main source of energy for cooking or lighting in some way in the previous 12 months, compared to less than 11% in the non-UBI villages.

Also Read: RBI rate cut: lending rate may not fall anytime soon as banks struggle on many fronts

In the case of tribal villages, 16% of households in the recipient village reported using a better cooking fuel and 14.5% reported improving their lighting, compared with practically no change in the control village. Indeed, about 13 bicycles were purchased in the UBI villages in comparison to only two in the ‘control’ area.

Even more encouraging was the weight of female children in the UBI villages. Just 39% of the girl children in the UBI villages and 48% in the ‘control’ villages had a normal weight. By the end of the experiment, there was a 20 percentage point improvement in the UBI villages as compared to half that in the ‘control’ villages. Not surprisingly, UBI also had a salutary impact on the enrolment of both boys and girls, but the improvement was far greater for girls. As many as 84.4% of boys in the 14-18 age group were enrolled in schools in the UBI villages versus 65.6% in the ‘control’ villages; in the case of girls, it was 65% in UBI villages versus 36.1% in the ‘control’ villages. As a result of greater enrolment, there was a 20% reduction in child wage-labour in the UBI villages compared to a 5% drop in the ‘control’ villages. There are several more instances of the beneficial changes brought about by UBI; those interested in more should read the report (goo.gl/xmAEGL).

The question that comes to mind, needless to say, is whether the changes are temporary, driven by the greater income with people, or whether they are lasting. Sewa Bharat-INBI decided to revisit the tribal villages several years after the pilot was over, in 2017, and that survey found that, while there were some slippages, in most areas, the older trends either continued or had strengthened. In continuation of the trend towards using more electricity in the UBI villages during the pilot, the legacy survey found that 24% of the former UBI families had got electricity in their homes as compared to 13% in the ‘control’ villages. In the pilot, 66% of UBI homes got water from a private source versus 38% in the ‘control’ villages; in the legacy survey, 65% of UBI households got water from a private source versus 55% in the ‘control’ houses.

In which case, the next government, whether that of the BJP or some other party, must look at ways to extend UBI in the next budget. And while many, such as this newspaper, believe that the government must do away with other subsidies such as those on food and fertilisers—(see goo.gl/tLwCeX on some of the leakages, or Economic Survey 2016-17 for a fuller discussion)—one of Sewa’s recommendations is that no subsidies be removed till the UBI is fully rolled out since low-income families could get hit if there is a problem/delay in the cash transfers as they will lose access to subsidised goods. That seems a reasonable caution, not an unsurmountable problem.