From eight thousand metres below the north Atlantic, the Antichrist calls out, using gravitational pulses unknown to science. A hundred conspiracies collide and explode: alien flying saucers; vaccine-induced AIDS; climate manipulation technology; that logo signifying modern capitalism, Coca-Cola, which conceals code proclaiming “without Muhammad” and “without Mecca”. The apocalypse is here; we just don’t recognise it.

“Now that we have seen each other”, the unicorn tells Alice, during her travels through Wonderland, “if you’ll believe in me, I’ll believe in you.”

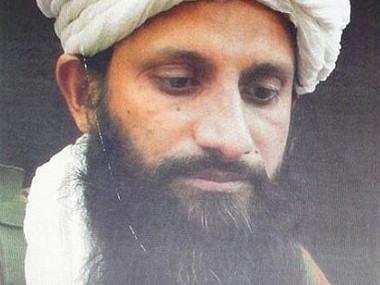

Asim Umar, the emir of Al-Qaeda’s Indian subcontinent branch, now confirmed to have been shot dead during a 23 September raid on a Taliban-run safe house in southern Afghanistan’s Musa Qala, might have liked those words.

Before he became one of the world’s most dangerous terrorists, Umar was the author of several best-selling dystopic jihadist fantasies. And before he became Asim Umar, he was Sana-ul-Haq, a peasant’s son from Uttar Pradesh, who disappeared from his home to begin a strange and secret life in Pakistan.

***

Educated at the neo-fundamentalist Dar-ul-Uloom seminary at Deoband in Saharanpur district of Uttar Pradesh, Sana-ul-Haq is believed to have gotten involved in violent Islamism after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in December 1992.

He, along with better-known jihadists like Abdul Karim ‘Tunda’, Azam Ghauri and Jalees Ansari, were part of the small cohort of young Islamists who emerged from the murderous violence of that winter, convinced that democracy was a failed god.

The Dar-ul-Uloom Deoband has no record of his graduating from the institution, according to its spokesperson, Maulana Ashraf Usmani, suggesting Sana-ul-Haq never completed a formal theological education.

In 1995, Sana-ul-Haq broke all contact with his family in Uttar Pradesh town of Sambhal and simply disappeared.

Fragments of the story, pieced together from interviews with sources inside Pakistan’s jihadist community, suggest he arrived in Pakistan in late 1995, possibly travelling on a forged passport. Sana-ul-Haq studied, for a time, at the Jamia Uloom-e-Islamia, a Karachi seminary that has produced several jihadist leaders, including Maulana Masood Azhar, the leader of the Jaish-E-Mohammed; Qari Saifullah Akhtar, who headed the Harkat-ul-Jihad-e-Islami, and Fazl-ur-Rehman Khalil, the leader of Harkat-ul-Mujahideen.

Late in the 1990s, after finishing his studies in Karachi, Sana-ul-Haq is believed to have joined Fazl-ur-Rehman Khalil’s Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, teaching briefly at the Dar-ul-Uloom Haqqania seminary in Akhora Khattak, and serving at the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen’s training camps in Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir.

Following the events of 9/11, sources said, Sana-ul-Haq moved back to Karachi, living from 2004 to 2006 at the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen’s office in Haroonabad. Sana-ul-Haq’s turn towards Al-Qaeda, according to sources who knew him, began in the summer of 2007, after General Pervez Musharraf ordered the storming of Lal Masjid in Islamabad, a seminary run by Jamia Uloom-e-Islamia alumnus Maulana Abdul Rashid Ghazi.

The Uttar Pradesh-born jihadist now turned to Muhammad Ilyas Kashmiri, a top jihadist with close links to Al-Qaeda. Interestingly, jailed 26/11 perpetrator David Headley had told the Federal Bureau of Investigation of a “Karachi project” run by Kashmiri, with plans to target India.

For several years after, he churned out a collection of what can only be described as jihadist pot-boilers — multi-edition bestsellers that give us fascinating glimpses into the inner world of Pakistan’s Islamists.

***

For Sana-ul-Haq, the apocalypse is a living, predatory thing: the fundamental physical reality, as it were, of now. In his 2007 opus, The Third World War and the Dajjal, Sana-ul-Haq tells how an epic civilisational war between Islam and its enemies will be preceded by the rise of the Antichrist.

“‘The sky would rain and the earth (would) yield crops, but neither would benefit the people, who would face drought”.

This, he says, is precisely what is happening, as a result of “policies concocted by the Jews”.

In Dajjal, Sana-ul-Haq describes the eve of the apocalypse as a time where the distinctions between the truth of Islam could no longer be discerned: “The propaganda during his time would be so ghastly that the truth would be presented as falsehood and the falsehood would be presented as the truth, and this twisted reality broadcast to the entire world.”

He notes that the “gravity of the Dajjal’s strife can be realised from the fact that even Prophet Muhammad used to seek refuge from his deceptive ability”.

The fortress of the demon Iblis, he goes on, is Hollywood, which “makes fictions appear real, and embeds itself in the minds of the so-called modern people”.

“The so-called modern class are dancing to the tunes of prostitutes, and calling themselves broad-minded — but in reality, their minds have been auctioned off in the markets of Hollywood,” he writes.

In The Bermuda Triangle, Sana-ul-Haq casts Muslim women as the key target of this satanic seduction. “Muslim women have been persuaded that their community cannot prosper unless they leave the home,” he argues, “but in fact, they are walking into a trap. By weakening the faith of Muslim women, the Devil succeeds in destroying their men.”

Sana-ul-Haq brought jihadism to a conservative middle-class, alarmed at the cultural strains imposed by modernity. In Dajjal, he wrote, “The tragedy of all Islamic societies is that they grow watching devilish Christian, Jewish and Hindu media… From childhood, our children are taught to dance to English and Hindi music. In fact, small children who are brothers and sisters are made to act in plays as husband and wife.”

Earlier, neo-fundamentalist figures had walked similar ideological ground, seeking to defend faith against the modern secular state. India’s Zakir Naik, for example, assailed modern, secular values, claiming “we Muslims would prefer that in India the Islamic Criminal Law be implemented on all the Indians, since, chopping the hands of a thief will surely reduce the rate of robbery in India”.

South African Islamist Ahmed Deedat, similarly, sought to legitimise polygamy, saying it resolved the problem of “surplus women".

“Ninety-eight per cent of its prison population is male,” Deedat claimed, “then, they have 25 million sodomites”.

***

Sana-ul-Haq held out jihad — the willingness to take lives and give one’s own — as a road-map for life in the shadow of the Antichrist. In an essay in the Summer 2013 issue of the Taliban magazine Azan, Sana-ul-Haq argued “that if jihad was not carried out, the earth would be filled with fasaad (strife), meaning that everything would cease to be at its fitrah (natural state).

“There is no fasaad greater than the world being ruled by man-made law instead of Allah’s law! When this happens, the world is filled with fasaad! Even the animals and birds start crying out; the earth stops growing its produce.”

In 1939, the patriarch of South Asian Islamism, Abul Ala Maududi, argued that the pursuit of political power was the raison d’etre of Islam, rather than what he called “a hotchpotch of beliefs, prayers and rituals”.

“Islam,” he wrote, “is a revolutionary ideology which seeks to alter the social order of the entire world and rebuild it in conformity with its own tenets and ideals.”

For Muslims, therefore, it was imperative to “seize the authority of state, for an evil system takes root and flourishes under the patronage of an evil government and a pious cultural order can never be established until the authority of government is wrested from the wicked”.

For Sana-ul-Haq, likewise, democracy is a din, a system of faith, and thus in irreducible opposition to Islam. In Adyan ka Jang: Islam aur Democracy (War of Faiths: Islam and Democracy), he wrote: “Democracy is evil and if you want to fight it, you have to destroy its four essential pillars: parliament, judiciary, civil bureaucracy and media.”

Early on, though, Sana-ul-Haq realised his project had little mass support in his homeland. In a 2013 essay in the jihadist magazine Azan, he railed: “The global jihad leadership feels justified in asking Indian Muslim scholars and masses as to why the jihad battlefields remain deprived of their blessed presence — especially when history shows that their ancestors always raised the banner of jihad against the enemies of Islam.

“The Red Fort in front of the mosque cries tears of blood at your slavery and mass killing at the hands of the Hindus.

“Is there no mother left in UP who can sing to her sons the songs that would inspire them to decorate the battlefield of Shamli instead of wasting their times in marketplaces, parks and sports fields?”

Little evidence exists that Sana-ul-Haq succeeded in drawing significant numbers of Indians to Al-Qaeda. Even though there were hundreds of cadre under him at Al-Qaeda camps in Afghanistan’s Sohrabak, the organisation was unable to mount a single successful operation in India.

But with the Taliban seizing power in ever-greater swathes of Afghanistan, there are growing opportunities for Sana-ul-Haq’s fantasies to be enacted, in flesh and blood.

His story has ended; his stories still live.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)