ILLUSTRATION BY Jerry Lemenu

Former Free Press Columnist Rochelle Riley studied how trauma and toxic environments impact how children learn. She unravels this issue through the eyes of three children and their caregivers in Detroit, Romulus and Flint. And she offers some solutions to ensure that children are mentally prepared to learn. This special report was sponsored by a $75,000 Eugene C. Pulliam Fellowship from Sigma Delta Chi. The award is given to "an outstanding editorial writer or columnist to help broaden his or her journalistic horizons and knowledge of the world" and can be used to cover the cost of study, research and/or travel that may result in editorials, writings or books.

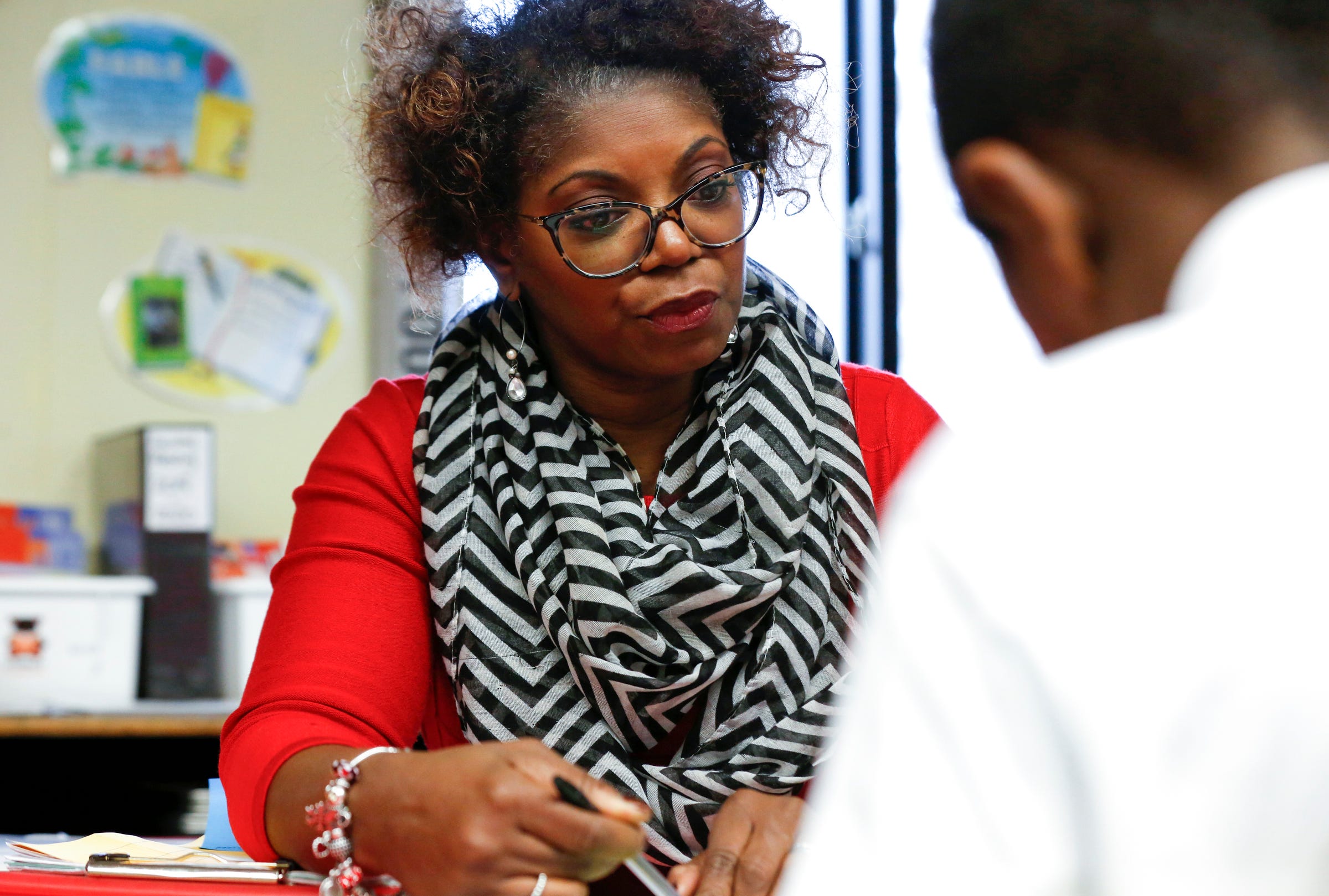

One wintry Tuesday morning, as Tavia Redmond welcomed her third-grade students to class, she asked young Michael why he had missed school the day before.

“He told me that the reason he wasn’t here was because he was dead,” she recalled.

“I said, ‘Well, you couldn’t have been dead and be back today.’ He said: ‘I was dead. I died over the weekend.’ ”

Later, Redmond learned that Michael's older brother had tried to kill himself — again.

And Michael had witnessed it. Again.

Then it was time for reading corner.

Millions of teachers, more than 80,000 in Michigan, also face the same challenge as Redmond, who teaches in the Romulus Community Schools — teaching traumatized children without being trained for it.

Thousands of children across Michigan have suffered adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and, or, the trauma of living in toxic or violent homes, neighborhoods or cities. The state of Michigan has no formal programs to teach teachers how to handle children in such pain. It also does not provide special funding or programs to deal with the growing challenge.

Behind every violent story, every murder, every massive car wreck, every case of physical or sexual abuse, every parent taken by cancer or a bullet, every broken home, there is a child whose life has been disrupted.

“At 8 o’clock on Tuesday morning, I saw one of my students,” recalled Michelle Davis, dean of climate, culture and community at Davis Aerospace Technical High School in Detroit. “I said, ‘Hey baby, where have you been? I’ve been missing you.' She said, ‘Yeah, I’ve been gone for two weeks. I was in a hospital. I tried to kill myself.’ And that was at 8’o clock. By 3 o’clock, I was sitting at my desk crying.

"My circle of concern is huge. But my circle of resources and what I can do … is minuscule.”

When children are traumatized, the pain disrupts their learning; it affects how they handle reading, writing and arithmetic. And the problem is more pronounced in urban, predominantly black school districts because black children are more likely to suffer from multiple adverse experiences, experts say.

“Our students come to us with so many challenges — things that we can’t even begin to fathom,” said Donise Floyd, director of the Romulus district’s special education department. Most of us have lived very sheltered lives or come from a different background. And our students are not so lucky, so many of them come to us with some things that many of us would only see on the news."

Of the 2,600 students in the Romulus schools, Michael’s school district, 400 have individual education plans, or IEPs, for special education services. Of those 400, about a third should not be in special education, Floyd said.

But there are no other options for students who have suffered trauma.

In many cases, school districts' answer to child trauma is to place children in special education classes, or to suspend them when their pain-induced behavior becomes intolerable.

- In Flint, one child was suspended or went home from school nearly 50 times. His mother contends that his behavior was a result of drinking lead-poisoned water for years.

- In Detroit, where one in 14 children experienced violence personally, according to a 2015 study, and there are no formal programs to help. Dr. Nikolai Vitti, superintendent of the 51,000-student Detroit Public Schools Community District, plans to change that. But it is an uphill battle since the state has no uniform policy or designated funding for trauma.

- And in Romulus, school officials are experimenting with a program to help traumatized students because many are in special education even though they have no learning disability.

The children I met in three Michigan cities while working on this project, are not broken children. They are little people whose lives have been cracked or damaged. And if they are left untreated, the damage will most certainly impede their learning.

How could it not?

Related stories:

► Traumatized kids are not a rarity in Michigan classrooms

► Flint boy was suspended, sent home from school 50+ times. His mom blames water crisis.

► Michigan's teachers, counselors experiencing trauma 'on a regular basis'

► Detroit teacher: I'll never forget day my students saw mutilated body on way to school

► He's changing the way Michigan teachers help children with trauma

► What we’re doing, not doing and should be doing

Another rocky start for Michael

Michael arrived in Tavia Redmond’s classroom at Wick Elementary exhibiting behavior that was unacceptable. But she didn’t know his pain.

“Day one — I didn’t really have a lot of background knowledge on what I was getting,” she said. “They told me I had a new student, and he was going to be getting special services, and he was in foster care. And I said, 'OK.'

“He came in the first day. I sat him down in his seat, and I introduced him to the class. No eye contact was given. He wouldn't even acknowledge me. He just sat. And he would blurt out lots of things. So, I said, 'OK. I don't know how to understand this one yet. I don't know where my voice level is going to go with him.' "

Redmond said attempts to include Michael in activities led him to scream at his classmates.

“And then he told me he hated me, that I was dumb, and he kept telling me ‘I don’t have to listen to you.’ ”

“Then he’d take off running.”

Redmond didn’t know that Michael, then 9, was haunted by memories no one had shared with her. So, she did what any teacher would do: She sent him to the principal’s office.

She would not learn for weeks that he’d been a victim of such emotional abuse that he sometimes could not help himself.

Redmond found out more about Michael on her own by calling his guardian to say she could not tolerate Michael’s behavior. Michael’s guardian said solemnly, “I’ve been waiting for your call.”

The guardian drove to the school, and caregiver and teacher had a long heart-to-heartbreaking talk about Michael.

Redmond learned about the emotional abuse, the trauma, the abandonment that Michael experienced, including him and his two siblings being left alone in an apartment without food or supervision, about his going through four teachers in a single year. And several times, Michael’s older brother tried to kill himself.

When the conversation was done, Redmond told his guardian, “I’ve got your back.”

From that point on, when Redmond needed help, she’d tell Michael: “I’m going to call your” guardian. “He was like, No. Please. I’ll be good. I’ll be OK. You don’t have to call.”

That kind of care, even discipline, was not something Michael was used to.

Michael is one of the lucky ones. He has his guardian, his social worker and his teacher to help him recover.

But it hasn’t been easy. His guardian recalls Child Protective Services questioning accounts of his brother’s repeated, attempted suicides, whether they actually happened.

“I told them, 'You don’t know what you’re talking about. I’m the one who had to cut him down!' ”

Yet Michael was expected to show up for school every day, read sentences, do math problems, spend hours with other kids he could not tell what was really happening with him and his family.

Teachers lack trauma training, resources

Across the nation, children’s trauma is being handled by teachers, equipped only with love and patience, rather than training.

Most teachers like Redmond, a 24-year veteran who has been at Wick for 20 of those years, do their jobs for the love of kids. She teaches language arts, social studies and science, and says she became a teacher, she said, "to make a difference in the world.”

“I love children, and my grandmother used to always say, ‘You need to teach them in the crib.’ And from the time I was little, I would play school with my little dolls, and my little stuffed animals. My first-grade teacher had a real impact on me. My kindergarten and first-grade teachers made me want to go home from school, and I would play school."

But she said, “I’m not paid enough for what we deal with.”

“The types of things I see ... I have seen kids come to school who have just left a home, and Dad has just been arrested,” she said. “Or maybe Mom or Dad or someone has just died, or their caregiver has just died. I've seen them come in and have lost brothers and sisters. I've seen them be taken away from the home. I've had students who have been put in a placement without our knowledge. …

“I had a student one year who was put in a respite center. And I didn't know,” she said. “I had to make a call to Child Protective Services to find out. When we were walking the kids out to go home, the child was walking to the (city) bus stop. And I'm like, 'Why aren't you getting on the (school) bus?' He said: 'I'm not living at home right now. I needed a timeout from the family. ' "

That child was a 12-year-old sixth-grader in Kalamazoo, where she used to teach.

Without preparation, teachers — even those used to working with students from dangerous neighborhoods and toxic environments — can be taken aback.

Redmond’s greatest lament: Michael does not have a severe learning disability, she said.

For those students forced into special education classes, the school district still must provide the extra care that, in most cases, it cannot afford.

“When you look at special education, it’s not the answer to all the world’s problems, and I think people are looking for help somewhere,' Floyd said. "The schools usually have to provide the umbrella of special services. So, we end up with a lot of the cases, whether (they belong) in special ed or not.”

Floyd said the Romulus district is trying to do more.

“We are working to build capacity for all teachers, train teachers,” she said, “to broaden their understanding and give them the tools they need to work (with these children) and support them.

She said a teacher asked about it aloud during a spring staff meeting.

“She said, ‘How do we do this? How do we?’ It was her very simple question. And it’s a very difficult question to respond to at times.”

Questions give rise to partial solutions

The Romulus district is experimenting with ways to offer services in an isolated setting in its high school, a positive behavior intervention system. But the program is new, and the need is great.

“We have to deal with everything going on with that kid,” Floyd said. “You can’t get to learning until you can get to that nurturing place and understand, intimately, what is going on with that child.”

The irony in Michael’s case, said his teacher, Ms. Redmond, is that he is so eager to learn that he insists on not being treated differently, even when he has so much catching up to do.

And he has to do it at a time when the Michigan Legislature has decided to require school districts to not promote third-graders this year who do not read at a third-grade level.

“Our whole school is going to become a third-grade school,” Redmond said in frustration.

Michael, she said “reads at a first-grade level, not because he’s not capable, but because he has had a disrupted education.

“He will try his hardest, and when you least expect him to understand something, he gets it, and he knows exactly what's going on!,” Redmond said. “So, I might want to take the learning disability out. I think it could be just the trauma there. If we're doing 20 questions, and I say, ‘I want you to do five on your own,’ he’ll tell me, ‘I’m going to do 10.'"