Will higher voter turnout help or hurt BJP?

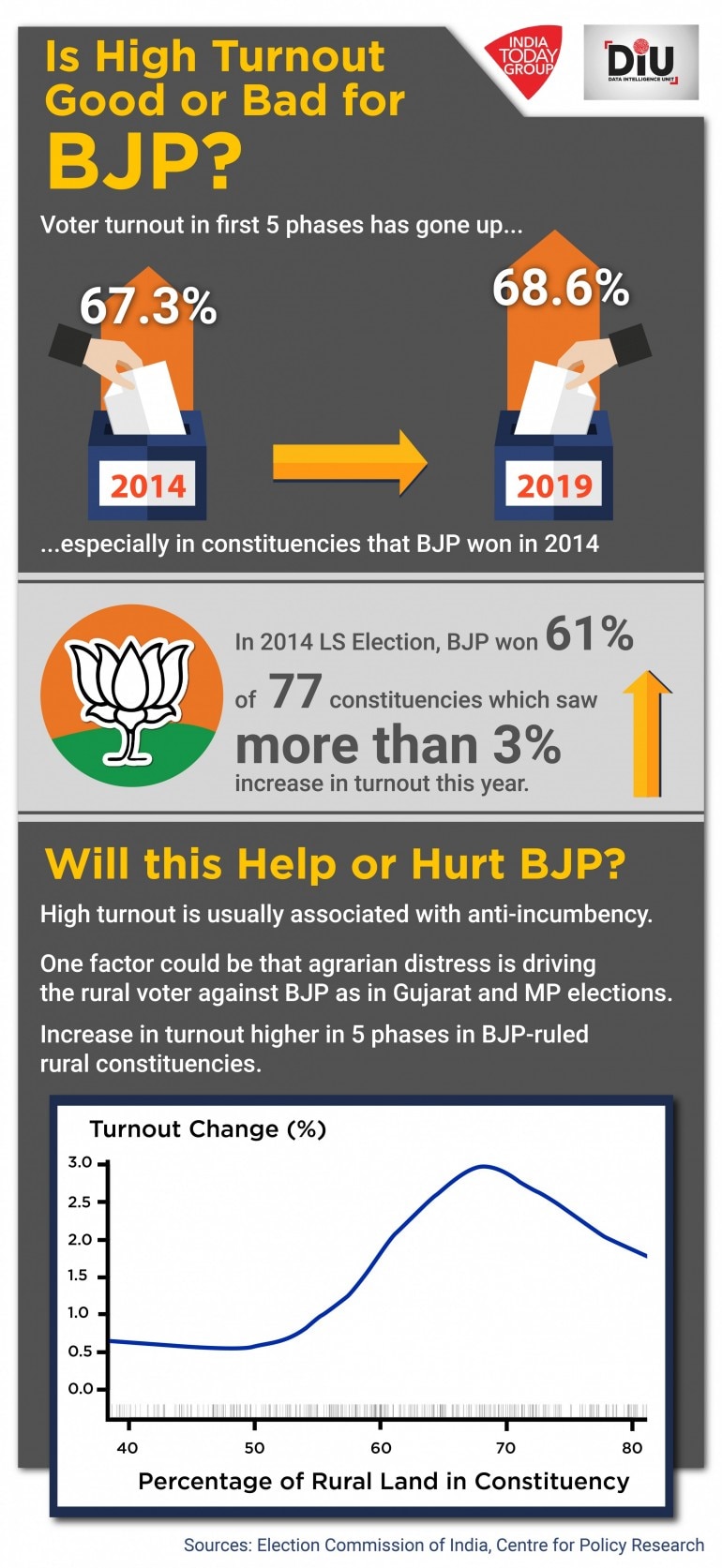

In the previous election, during the Modi wave, India saw its highest ever turnout at 66 per cent. Surprisingly, the turnout numbers so far in 2019 are actually somewhat higher than in 2014. Through the first five phases, the constituencies that have gone to the polls have registered an average turnout of 68.6 per cent - marginally higher than the 67.3 per cent the same constituencies registered in 2014.

Six phases are over for the 2019 Lok Sabha election, and while we still have the last phase to go, certain patterns are starting to emerge. One of them is the voter turnout in each parliamentary constituency, the only verifiable information available during an election as it is furnished by the Election Commission of India (ECI). By comparing turnout in 2019 to the previous Lok Sabha election in 2014, we can make inferences about who is or is not motivated to cast their ballot this time.

In the previous election, during the Modi wave, India saw its highest ever turnout at 66 per cent. Surprisingly, the turnout numbers so far in 2019 are actually somewhat higher than in 2014. Through the first five phases, the constituencies that have gone to the polls have registered an average turnout of 68.6 per cent - marginally higher than the 67.3 per cent the same constituencies registered in 2014. But there is a significant variation in this change, from a 12.8 percentage point drop in Nagarkurnool in Telangana to a 16.6 percentage point increase in Khajuraho in Madhya Pradesh.

So, what does this turnout mean? As I have argued elsewhere, usually an increase in turnout is associated with anti-incumbency in the national election. In this case, it would imply that an increase in turnout is associated with a vote against the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). On the other hand, BJP partisans argue that its superior party machinery and funding make it far more efficient turning out BJP supporters to the polls.

WHERE ARE PEOPLE TURNING UP TO THE POLLS?

In order to make sense of the data, I removed results from Telangana due to a sharp drop in turnout, which could bias the resulting claims, as well as small union territories due to challenges in data quality. This leaves us with 402 (out of 543) constituencies for the analysis. I further classified a "high turnout increase" constituency as one with at least a 3 percentage point increase in turnout - corresponding to the top 20 per cent of turnout increases in this election. Of the 77 high turnout increase constituencies that have gone to the polls till the fifth phase, BJP won 47 (61 per cent) in 2014. Of the remaining 325 constituencies, BJP won only 154 (47 per cent).

This strongly suggests that people are motivated to turn out precisely where BJP is ruling. This could be due to either strong anti-incumbency that seeks to hold BJP to account, or due to strong BJP organisation bringing supporters to the polls in places where the party is in power.

ANTI-INCUMBENCY OR BETTER PARTY ORGANISATION?

To understand whether anti-incumbency or party organisation is motivating voters to come to the polls in BJP-ruled constituencies, I looked at the role of urban and rural voters in determining turnout increase. A major narrative leading into the national election was that agrarian distress was driving the rural voter against BJP, and there was empirical evidence for this from the recently concluded Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh state elections.

Typically, the classification of rural and urban constituencies is quite difficult, as most of the time it is based on haphazard rural/urban classifications in an out-of-date Indian census (the last one was in 2011). Satellite imagery from European Space Agency from 2015 provides a more robust, albeit technical, approach to classifying rural land - by classifying the percentage of the land in a constituency that is rural in nature.

Shamindra Nath Roy, from the Centre for Policy Research (CPR), has graciously provided me with these estimates for each parliamentary constituency in India. The figure displays the relationship between the percentage of rural land in a constituency and the turnout increase among the 201 constituencies the BJP won in 2014 (for which I have data). In order to statistically model this relationship, a method known as locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) has been used.

As the figure shows, the percentage of rural land in a constituency (i.e, the extent to which a constituency is rural) is highly associated with an increase in turnout change in BJP-ruled constituencies. The median percentage of rural land in a constituency is 61 per cent in constituencies in which the BJP won in 2014. When a BJP-ruled constituency had below 61 per cent rural land, there was an average turnout increase of 0.9 percentage points, but when it had more than 61 per cent rural land, there was an average turnout increase of 2.4 percentage points.

Taken together, the turnout patterns in this election thus far point to some anti-incumbency for the BJP in rural areas.

However, some caveats are in order. First, the levels of turnout change are quite modest compared to 2014, as the average turnout went from 57 per cent in 2009 to 66 per cent in 2014 across India. Even if turnout change is associated with anti-incumbency, it may not be enough to wipe out the large victory margins the BJP established in 2014.

Second, while these data patterns are suggestive of anti-incumbency, it may be that the BJP has become particularly good at mobilising voters in rural areas.

Finally, there are myriad bureaucratic factors that affect the calculation of voter turnout, in particular, the quality of the voter list maintained in the constituency.

Nonetheless, we are witnessing some significant increase in turnout in states like Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, which requires attention and analysis. We will have to wait until the election results come out before we really understand the meaning of these turnout patterns.

(The author is a political scientist and is a professor at Ashoka University)