Meghalaya illegal mining: Digging their own grave

Another mine accident puts the spotlight back on Meghalaya's illegal coal extraction trade and the ecological devastation from it.

A dense forested hill on one side and barren plains-randomly excavated in search of coal-on the other, Lumthari is a tiny, almost inaccessible hamlet in one of the remotest corners of the Jaintia Hills in Meghalaya. At first sight, the village looks a picture of pastoral bliss: men and women basking in the winter sun, children playing with puppies and piglets and pulling carts made of the bark of betel nut trees. But under the bright facade lurks a shadow of gloom: three of Lumthari's young men, trapped in a coal mine in Ksan-21 km away by motorable road and a 15-minute trek through the hills-since December 13 last year might never come back again.

For most part of the last month, 40-year-old Jostina Dkhar has not budged from the doorstep of her home-a rectangular room with a tin roof-in the desperate hope of seeing the bodies of her sons, Melambok, 22, and Dimonmi, 20, one last time. Giving her company is 50-year-old Rita Dkhar, whose son Chalabas, 20, is also feared dead in the same mine where 15 workers got trapped. Jostina, who was abandoned by her husband a decade ago, suffers from an undiagnosed disease. There is little hope of medical help as the nearest health centre is 32 km away and she will have to walk at least 10 km to find public transport. Her elder daughter, 12, cannot study further as the village has only a lower primary school. With the two earning members of the family gone, the education of the younger daughter, 7, too, is uncertain.

There is no rice at Jostina's home. Her daughters eat pineapples found in the nearby hills during day and rice offered by neighbours at night. To even encash the Rs 1 lakh cheque provided by the government as compensation, Jostina will have to travel 35 km to open a bank account. Her failing health does not permit that. The Ksan mine mishap that has caught national attention has pushed Jostina and her family to the brink.

The disaster has also exposed how mine owners' insatiable greed and the lack of alternative livelihood for the majority of Meghalaya's poor population have ensured the continuation of the hazardous rat-hole mining, despite a ban imposed by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) in 2014. Unregulated mining is so rampant in the state that several deaths go undetected and unreported almost every month. Amid the ongoing rescue operation at Ksan, the bodies of two coal miners were discovered on January 6 at an illegal mine, 30 km away, in the same East Jaintia Hills.

Miners' safety, however, wasn't the only reason behind the NGT ban. The order came on April 17, 2014, after the All Dimasa Students' Union in neighbouring Assam filed a petition that untreated toxic discharge from coal mines in Meghalaya was polluting streams and rivers in Assam. "The rampant mining has caused large-scale denudation of forest cover, scarcity of water, pollution of air, water and soil, and degradation of agricultural land," says Professor O.P. Singh of the Shillong-based North-Eastern Hill University. The NGT based most of its order on a report prepared by Prof. Singh.

Most rivers and streams in the mining belt have turned acidic, the colour of the water turning brownish orange. Many villages are facing acute shortages of drinking and irrigation water. Samples from almost all rivers in the Jaintia Hills have shown pH levels of around 3, way below the range of 6.5 to 8.2 that is considered optimal for most organisms. "Villagers who depended on fishing are now left with dead rivers," says H.H. Mohrmen, an environmental activist from Jowai.

Though the Lytein river flows by, Lumthari villagers walk miles to fetch drinking water. Jostina says the paddy yield from her farm patch by the river has been decreasing every year and doesn't suffice for the family. "We cannot use the river water anymore. People say it's poison," she says. Her neighbours, who fear coming on record or being photographed, say community land that was earlier used to produce orange, pineapple, banana and jackfruit is being taken over by mine owners, by force or deceit. "The mines have poisoned our land. We cannot grow anything and are forced to work in the mines," says a villager.

Driving down from Shillong to Khliehriat, the epicentre of illegal coal mining in the state, the visibly disfigured Jaintia Hills and the unending dumps of coal hide a dirty secret-abandoned rat-hole mine pits and caves. Nobody knows for sure how many of these exist. According to Balios Swer, president of the Jaintia Coal Miners and Dealers Association, some 60,000 mines spread across 360 villages exist in the East Jaintia Hills alone. The mines remain death traps even after all the coal has been extracted as the abandoned pits are left uncovered. "There are thousands of such big holes. Many children and livestock have fallen into these mines and died," says Rosanna Lyngdoh of the Impulse NGO Network, which works for children. "Hardly ever is a complaint lodged as poor villagers dare not confront the powerful and politically connected coal barons."

In August 2018, the NGT formed a three-member committee, headed by retired Justice B.P. Katakey, to assess the steps taken by the state government to undo the environmental damage caused by rat-hole mining. The committee found that little had been done. "We found freshly mined coal, certainly not what was mined way back in 2014. We also found stacks of coal in one location at Sutnga in East Jaintia Hills," says Justice Katakey.

It was near Sutnga that RTI (Right to Information) activist Agnes Kharshiing and her companion were attacked on November 8 last year. Nidamon Chullet, the prime accused in the attack, is not only a coal lobbyist but also a member of the ruling National People's Party (NPP). "Coal is being extracted illegally with tacit support from the state government," alleges Lyngdoh.

Coal mining has flourished in Meghalaya under political patronage. A citizens' report, prepared by activists, filed in the Supreme Court in December last year, accuses top politicians of having stakes in the industry. They include Kyrmen Shylla, minister for revenue, disaster management and social welfare and MLA from Khliehriat; Lahkmen Rymbui, minister for environment and forests; Comingone Ymbon, minister for public works; Sniawbhalang Dhar, minister for commerce and industries and transport; Vincent Pala, Congress Lok Sabha MP from Shillong; and Dikkanchi D. Shira, Mahendraganj MLA and wife of former chief minister Mukul Sangma.

According to government estimates, Meghalaya, which makes up just 0.68 per cent of India's total area and accounts for 0.24 per cent of its population, has 576.48 million tonnes of sub-bituminous coal. The coal mining boom in the state has seen annual production rise from 39,000 tonnes in 1979 to 5 million tonnes in 2014-1 per cent of India's total coal production at the time. Prior to the NGT ban, coal mining contri-buted 7-8 per cent to the state's GDP and accounted for 27 per cent of the revenue.

Political analysts say mining is the biggest source of electoral funding in the state and the Mukul Sangma-led Congress government lost the 2018 assembly election as it failed to get the NGT ban revoked. "The mine owners together earn at least Rs 2,000 crore a year," says a politician who did not want to be named. Meghalaya chief minister Conrad K. Sangma's NPP-an ally of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) at the Centre-had promised before the assembly election that it would get the mining ban lifted and even challenge it in the Supreme Court. "The ban (on mining) is not the solution. I have, however, maintained that the safety of mine workers and environmental protection can never be compromised," says Sangma. "I want the ban to be lifted, but at the same time reiterate that coal mining in Meghalaya cannot be done the same way as before. Banning it is not the solution because people have been doing that for the past 100 years."

Pala, who owns 24 sq. km of coal mines, agrees with the chief minister. "The ban is unfair to Meghalaya, where the topography necessitates a different type of mining," he says. While political groups have favoured 'regulated mining', successive governments have done nothing to overturn the environmental damage. The NGT forced the government to keep the penalty collected against transportation permit for coal extracted before the 2014 ban in a separate fund-the Meghalaya Environment Protection and Restoration Fund. A sum of Rs 433 crore has been collected so far, but the government is yet to initiate a restoration project and put it to use. On January 4, based on the Justice Katakey report, the NGT asked the Meghalaya government to deposit another Rs 100 crore to the Central Pollution Control Board towards restoration of environment in the state.

Experts say scientifically done mining will be equally damaging. "In Meghalaya, coal is found 200-300 feet below the ground level, unlike Assam and Jharkhand where it is 15 feet below," explains Naba Bhattacharjee, a Shillong-based commissioner with the NGT. "The width of the coal seam is 2-3 feet, but it runs horizontally. In other places, the seam is much broader and vertically deep. To extract the same amount of coal that one can get within a kilometre in other parts, one has to mine for several kilometres." Shillong-based environmental activist Angela Rangad concurs: "Scientific mining will mean faster plundering of the environment. And it also doesn't make economic sense as Meghalaya coal is not of high quality."

Travelling to Meghalaya by road, one often encounters massive traffic snarls caused by coal-laden trucks. They are on the road because in at least seven consequent orders, the NGT and the Supreme Court, hearing petitions by coal mine owners, truck operators and weighbridge operators, allowed the transportation of an estimated 1.76 million tonnes of coal extracted before 2014. In November last year, the Sangma government challenged the NGT ban in the Supreme Court. On January 15, the Supreme Court banned transportation of coal till February 19, refusing to grant more time.

Activists claim the mine owners took advantage of the permission to mine fresh coal, transporting an estimated 5.5 million tonnes. "The miners exaggerated their declared amounts of previously mined coal and transported the freshly mined coal," alleges Mohrmen. Swer, however, denies illegal mining and calls the Ksan mishap "an isolated case". Minister Kyrmen Shylla claims to have stopped coal mining since the NGT ban in 2014. The very next year, though, his father Kor Sympli was arrested on charges of illegal mining. "We did not want to do mining. But for the labourers, it was the only source of livelihood and they wanted to continue. My father did not stop them on humanitarian grounds," said Shylla.

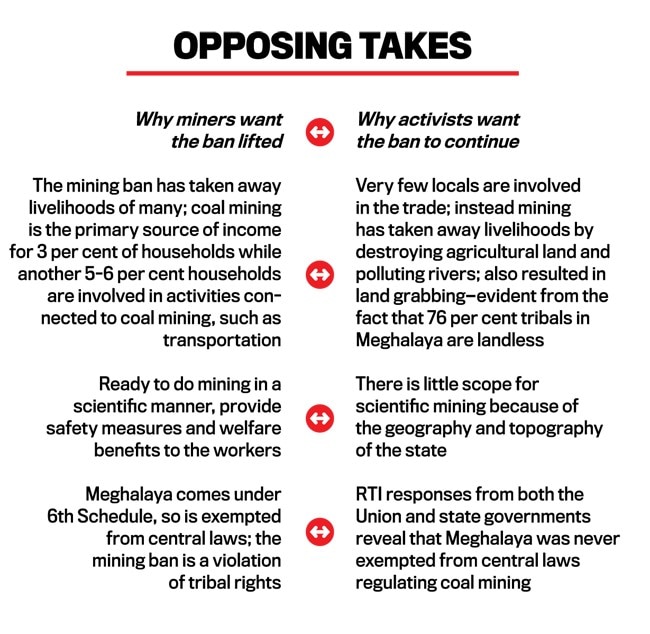

Activists, however, claim few locals are voluntarily involved in mining. 'Coal-bearing areas in many villages have been consolidated under the ownership of a few large-scale mine owners, leaving many landless. Their livelihoods have been affected, and many are excluded from the web of activities connected with coal mining,' says the citizens' report.

Land in Meghalaya is owned privately or by a community and protected by the autonomous district councils formed under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution. The government has control over only 5 per cent of the land. Before the NGT ban, mining was being carried out without government regulation on the pretext that it was being done on Sixth Schedule land. Ironically, an RTI response from Meghalaya's Directorate of Mineral Resources (DMR) on February 5, 2009, reveals that the state's coal mines had not been exempted from the purview of the Coal Mines (Nationalisation) Act, 1973, as amended in 1976, and a mining lease was mandatory.

The Meghalaya government, too, in a status report to the Supreme Court, said that the state was not exempt from central laws on mining.

Coal miners and the state government refer to a July 2, 1987, letter written by then energy minister Vasant Sathe to the then Meghalaya chief minister W.A. Sangma, stating that the Union government had 'no desire or intention of disturbing the customary tribal rights or causing any hardship to them'. What is conveniently forgotten is that the letter also categorically stated that traditional mining by the tribal people could continue as per the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957. 'Coal India Limited would be willing to give any assistance or advice the state government may require for carrying on mining on a scientific basis and keeping in mind the safety and health factors,' stated the letter.

Unregulated coal mining in Meghalaya has destroyed the structure of tribal community land holding, resulting in large-scale land alienation and displacement of tribal poor. The Socio-Economic Caste Census 2011 reveals that 76 per cent of the local tribal community is landless. "Landlessness has increased in places where coal mining has been taking place," says Tarun Bhartiya, a Shillong-based activist and filmmaker.

Though the land belongs to the community, individuals with vested interests coerce the community to part with it. The son of Nau I Kyrmenshuh, the headman of Nonkhleih village in the vicinity of the area where 15 miners are trapped, was hacked to death allegedly by the coal mafia because his father resisted the use of village land for mining. Influential people also manipulate the autonomous district councils to claim title or lease of land in the coal-rich areas. "Since the state does not have proper records of land titles or deeds and customary practices, dubious land deals are rampant," says Mohrmen.

Sudden inflows of coal money have disrupted the largely egalitarian tribal social order and created socio-economic inequalities. The person who owns the land with coal deposits or takes it on lease from the village community is known as the 'owner' of the mine. He employs supervisors to organise the extraction and transportation of the coal. "A 100 feet wide coal mine produces 30-40 tonnes of coal daily. The owner earns Rs 1,000-2,000 per tonne while supervisors get Rs 7,000-10,000 per 10 tonnes," says a mine owner. Not surprisingly, the owners live in palatial homes in urban locations, drive swanky cars, send their children to residential schools and colleges abroad and, above all, have a grip on the state's political network and administration.

While most owners and supervisors are locals, the labourers who risk their lives in the rat-hole mines are usually from Nepal, Bangladesh, Assam and the state's outskirts. "These workers come here to escape poverty. They are not provided any safety equipment or insurance and work in hazardous conditions. They regularly die, nameless and away from the spotlight," says RTI activist Kharshiing. Rat-hole mine workers overlook the risks because of the relatively high wages they earn-Rs 600-2,000 daily. "We crawl up to 30 feet inside the rat hole, which could be 3-4 feet high. We know there is a risk of being trapped in water or buried alive in case of a cave-in. But we don't get so much money in any other work," says Rekibuddin Ali, a worker from Assam's Chirang district. Ali says his brother died inside a mine about three years ago. There was neither a police case nor any compensation.

The workers live in shanties, made of bamboo with plastic sheets as roof. Their day starts with the first ray of sunlight and ends at sundown. Despite the inhuman living conditions and risk their job entails or the environmental damage from illegal mining, the workers carry on, desperately needing the money they earn and well aware that no better, safer employment awaits them. Over a decade ago, former Lok Sabha speaker and Meghalaya chief minister P.A. Sangma, the father of chief minister Conrad, had talked about finding alternative livelihoods for the state's people as coal would not last forever. Time for the son to act on his father's vision?