California to towns defying the COVID-19 shutdown: No cash for you

It was a boast heard around this Central Valley town of 30,000, courtesy of Mayor Paul Creighton.

Atwater had not just flattened the COVID-19 case curve. “We’ve smashed the curve,” he declared.

With just 12 confirmed cases, the City Council in mid-May declared Atwater a “sanctuary city” for business, allowing all businesses to reopen in defiance of California’s shutdown orders.

How times have changed.

Cases have surged past 800 in Atwater. Merced County is on the state’s coronavirus watch list. And federal officials have declared the rural, agricultural Central Valley one of the nation’s most worrisome hot spots for the spread of the virus.

What has not changed is Atwater’s defiance. City leaders refuse to rescind the sanctuary city resolution — despite the state’s withholding federal emergency coronavirus relief funds because of it.

“They have tried to put a gun to our heads to make us fold,” Creighton said at a recent City Council meeting. “They want our citizens to feel scared and vulnerable. Don’t be. They want to increase political heat or we become the next victim in a long line of victims in today’s cancel culture.”

Unless Atwater scraps its sanctuary city resolution, the state will withhold up to $387,428 for which the city is eligible because it is violating state public health rules, the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services told city leaders late last month.

The state has already withheld the Atwater’s first allocation of $64,833, said Brian Ferguson, a spokesman for the state emergency services agency.

“Any municipality that takes actions that endanger the health and welfare of its citizens, the state is going to take a close look at,”Ferguson told The Times.

The tussle comes as COVID-19 cases have exploded in Merced County. The county had 5,012 confirmed cases as of Friday. On June 6, it had just 343 cases. Atwater had 831 confirmed cases as of Friday. On June 6, it had confirmed 32 cases.

Atwater has more coronavirus cases per capita than Merced county’s two largest cities, Merced (population 83,000) and Los Banos (population 40,000), according to a Times analysis. Despite being home to 10.6% of the county’s population, the city has about 16.6% of known infections in the county.

While California’s second surge of coronavirus this summer is showing signs of stabilization, the increased spread in the Central Valley are a source of deep worry among physicians and public health officials.

“Although L.A. may be looking a bit better, there’s significant movement of virus from Bakersfield all the way up the Central Valley into Stockton,” Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House’s coronavirus response coordinator, said in a recording of a conference call obtained by the Center for Public Integrity.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has identified the Central Valley as a region in great need of resources to slow the spread of the virus. He is sending “strike teams” of state, federal and local personnel there and asked state lawmakers to approve $52 million to improve testing, tracing and isolation protocols in eight counties: San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Merced, Madera, Fresno, Kings and Tulare, and Kern.

Newsom’s decision to target the Central Valley coincides with his funding standoff with Atwater and Coalinga, a city of 16,000 in Fresno County.

On July 23, Mark Ghilarducci, director of the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, sent letters to the city managers of Atwater and Coalinga, which passed a resolution in May declaring all businesses to be essential.

Coalinga’s share of the federal funds, Ghilarducci wrote, would have been up to $212,358. The state has already blocked the first allocation of some $36,000.

“In order to be eligible for funding, assuming it meets the other prescribed criteria, the city would need to rescind this resolution,” Ghilarducci wrote to both cities.

The state says the cities are violating rules that govern the distribution of $1.8 billion allocated to California through the federal CARES Act. California’s largest communities received money directly from the federal government — a total of $5.8 billion to counties and cities with populations over 500,000 — while the state budget includes a detailed plan to help less-populated areas.

Neither Atwater nor Coalinga will budge.

Coalinga City Manager Marissa Trejo said that, after receiving the letter, she invited state officials to participate in a special City Council meeting via Zoom to discuss rescinding the resolution. They declined. The City Council voted to reaffirm it.

In emails that she shared with The Times, Trejo told Office of Emergency Services officials that Coalinga was “being held to a higher standard” than other cities in order to receive the funds. Other cities might not have resolutions, she wrote, but “they are not enforcing” state health orders.

“To be honest,” she wrote, “I am not aware of any businesses in Coalinga operating against the existing orders. There is nowhere in Coalinga that I can dine in. None of our restaurants are even offering outdoor dining. I have not seen a single hair salon, barbershop or nail salon open.”

In Atwater, the politically potent “sanctuary city” label won support from officials across the U.S. and quickly landed Creighton on “Fox & Friends,” where he called state lockdown orders “draconian.” But it also provoked anger among some residents who called it political grandstanding.

Despite its defiance, the city last week posted on its Facebook page photos of municipal employees covering their faces and wearing matching T-shirts that said, “Mask Up Atwater.”

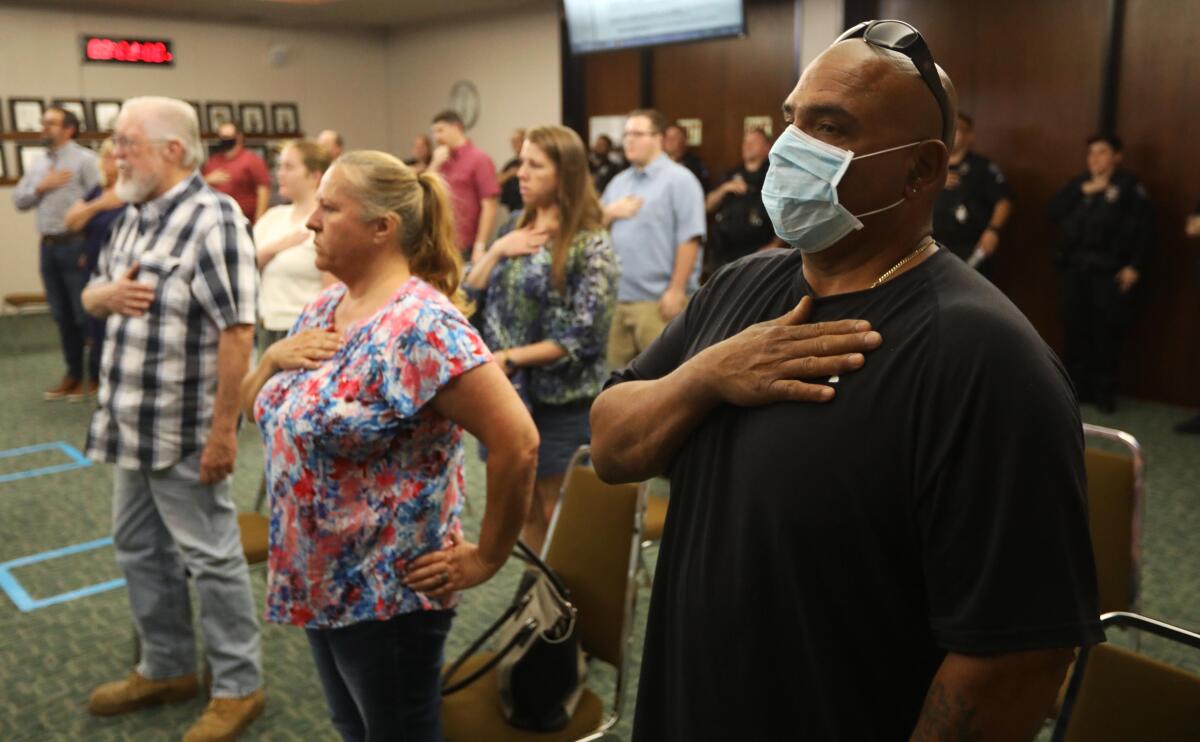

At a raucous City Council meeting last week, members of the Freedom Angels Foundation — best known for their anti-vaccine activism — rallied outside City Hall in support of the sanctuary city resolution. In a Facebook video beforehand, the group’s co-founders said Creighton had reached out to them and asked them to show up and “wear red as a sign of solidarity.”

At the meeting, officials — including the city manager, two council members and the police chief — who were not publicly covering their faces around the time the resolution was passed, wore masks at times. Creighton took his off while he was on the dais.

Resident Mary McWatters said she was baffled the financially strapped city was willing to lose emergency funds.

“Mr. Creighton, you believe that your constituents and Donald Trump are on your side,” she said. “Well, Donald Trump is not going to bail this city out.”

Resident Theron Sanders Sr., wearing a star-spangled bandanna around his neck, said he masked up in public to keep mom-and-pop businesses in compliance with safety rules and, therefore, open. He wanted the sanctuary city resolution left in place.

“We need our economy to be able to continue to grow,” he said. “We need to be able to stay open. ... I believe this ‘plandemic’ is entirely designed to not only bring down our economy but to destroy our president.”

The shutdowns walloped Atwater just as it was starting to claw back from the Great Recession. Last year, the state auditor ranked Atwater the second-most financially distressed city in the state, behind Compton.

Creighton said the city has since balanced its budget and did not count on getting state or federal help anyway.

Newsom, he told The Times, is “just downright bullying” his city. Creighton said he was only trying to help small businesses devastated by the shutdown orders, which allowed chain retailers such as Walmart and Target to stay open, with varied compliance with safety rules.

Among the facilities in Merced County with an active COVID-19 outbreak is the Walmart Supercenter in Atwater, according to the county.

“The only thing we did with the sanctuary city is allow businesses to open up,” Creighton said. “We still socially distance. We still wear masks. We still do good hygiene. ... It seems like we’re arbitrarily being picked on.”

Times staff writer Sean Greene contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.