After major stroke, John Jackson Jr. sets goal to return to Coliseum to watch his son, John III, play for USC

The doctors told John Jackson Jr. and his family that his upcoming surgery had been honed in the crucible of war. If a soldier’s brain was wounded in battle, they would open his skull and remove a slice to relieve pressure. That piece of cranium would then be inserted into the stomach, preserved there until the swelling decreased enough to put it back where it belonged.

John Jr. did not know whether the surgeons at Torrance Memorial Medical Center would be able to take him apart and reassemble him like those soldiers. He believed — they had kept him ticking for more than a month since the stroke — but he still had to be realistic about all of the possibilities. At just 52 years old, that meant he needed to have a talk with his oldest son.

On a January morning, John Jackson III drove down to the South Bay from USC, the school of his dreams, to see the man who planted that seed without really having to try. John Jr.’s short-term memory was strained, but he remembered very well what it was like to be a freshman wide receiver for the Trojans. If he had a bad practice, he would be so hard on himself. Now he was about to put a teenager’s problem into proper perspective.

When it was time for surgery, John Jr. wanted John III by his side. His wife and two younger kids stayed behind as the men of the house rode an elevator down to the operating room floor. The ability to communicate without sign language or John Jr. pointing at pictures to convey a simple message felt like an immense gift, and yet, here was Dad, going back under.

“This is serious. There’s a chance I might not make it out,” John III recalls his father saying in the stark cold of the surgery prep room. “I want you to know that no matter what happens I need you to take care of the family.”

John Jr. apologized to John III for being in this situation. Taking care of the family actually meant taking care of himself first — getting started on his real estate major, meeting the right people in the famed Trojans network and establishing himself quickly in the USC football program as more than a legacy roster holder — all the while taking younger brother Jaden to his baseball games on the weekends and being there for his mother and sister, too.

The message would change John III forever. No matter what happens. Those were the key words. Dad wasn’t telling him to grow up only under the condition that he died. He was telling him he had to grow up — period. That he might have to do it without his personal life coach directing him was just an unfair obstacle.

John Jr. had said what he needed to say. He was all prepped now. The Torrance Memorial staff wheeled him into the operating room, leaving John III alone.

His thoughts turned to something as simple and digestible as football. John III decided he was going to work so hard to become a better player that when his dad came to USC football practice in the spring and looked at the wide receivers, John Jr. wouldn’t even be able to pick him out in the crowd of potential All-Americans and future pros. Oddly, John III’s goal for his freshman season was to blend in.

::

On Dec. 4, the day the stroke silenced John Jackson Jr., John III sat down to write the first of 17 letters to his dad.

“Today, I got my classes at USC,” John III typed into his laptop. “I was able to sit down with Sonia, and she helped me pretty much with 100 percent. She really likes me, possibly more than you.”

Since John III couldn’t talk to his dad, he wanted to write exactly as they talked, the sentences tinged with biting sarcasm and the tough-love mentality that defined his rearing. Of course Sonia Savoulian, the associate director for Programs in Real Estate at the USC Price School did not like him more than Dad, but John III thought John Jr. would find that funny.

“Usually,” John III continued, “this is the part where you would say, ‘Oh son, that’s good, because she’s a powerful person, and you will need her a lot more than she needs you.’ ”

It would be easy to see John Jackson III playing football at USC as a boy living out the dream his father set out before him, but that would be an incorrect assumption. In truth, John III deciding during his senior year at Gardena Serra High that he wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps to USC instead of pursuing a professional baseball career signified the young man stepping out on his own.

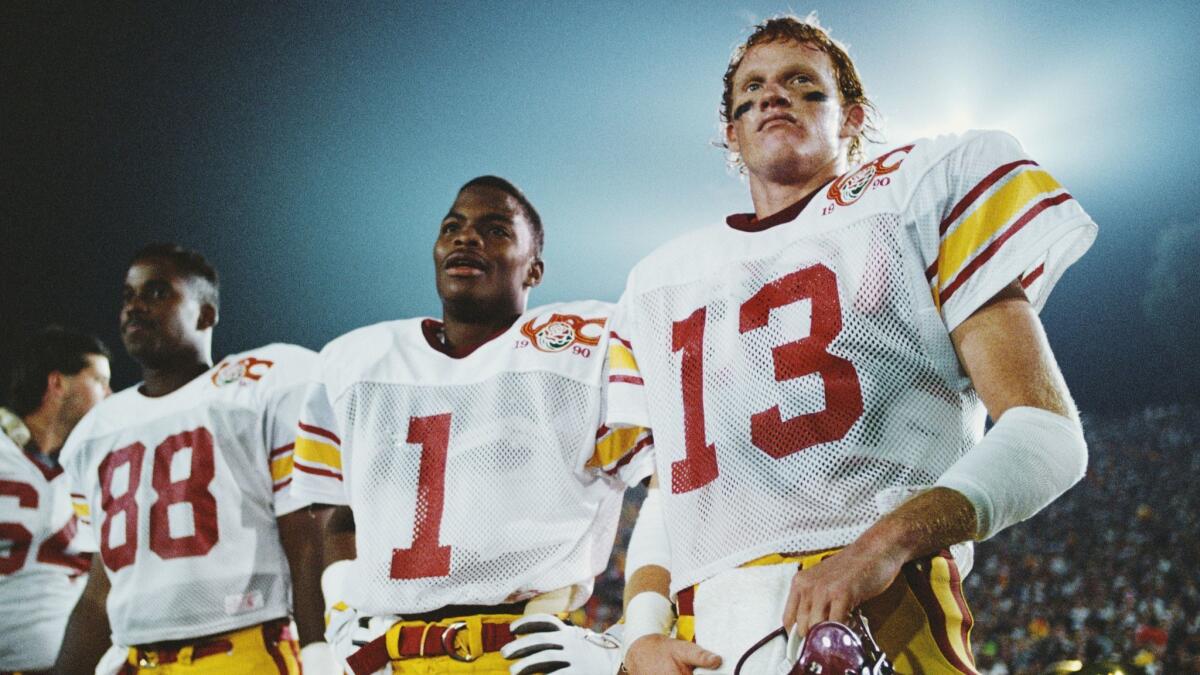

His old man’s thoughts on the topic were complicated, to be sure. But John Jackson Jr., he of the one-time-record 163 career receptions, of the 1989 All-Pac-10 first-team designation, of the two-time Academic All-American honors, did not want his boy to play football for USC. As he aged, despite his lifelong devotion to Trojans football, John Jr. more identified with the forgotten side of his athletic resume as a first-team All-Pac-10 baseball player, leading the team in hitting one season and setting the school record for stolen bases.

Baseball came so easy for John III, and in Dad’s mind, football was just another sport to help round out his adolescent experience, another passion they could share.

But really, what could John Jr. have expected? He raised the boy in cardinal and gold, taking him to the Coliseum and to campus often once John Jr. joined Pete Arbogast in the radio broadcast booth. On John III’s bedroom wall hung a framed photo of his dad in a USC uniform and another of Pete Carroll.

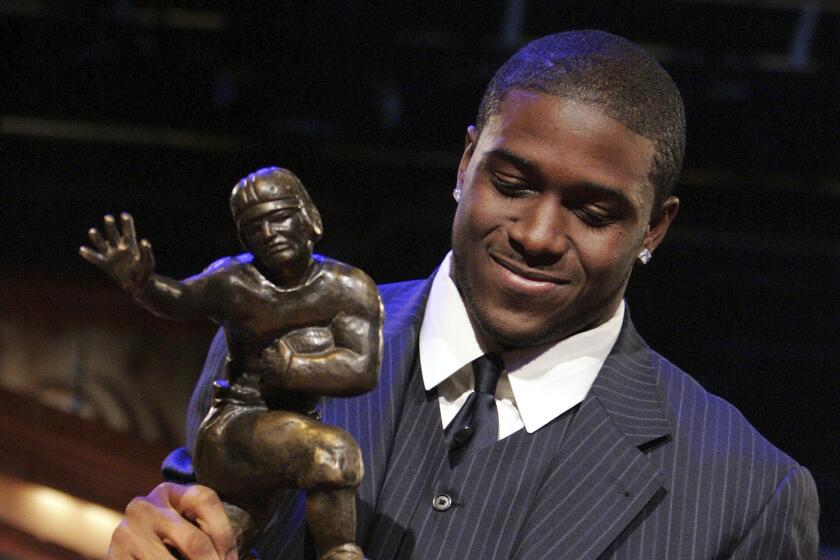

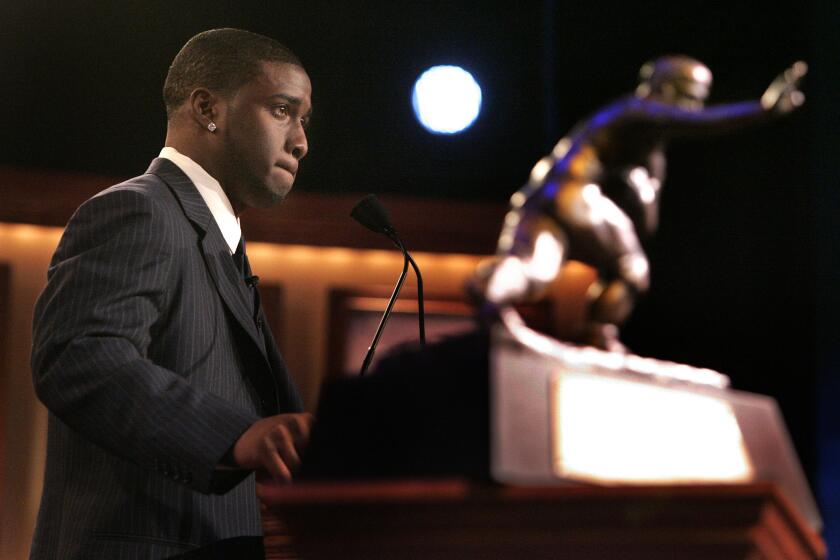

It had been the same way for John Jr. growing up, with John Sr. coaching the Trojans running backs and John Jr. collecting the game-worn wristbands of Heisman Trophy winners Marcus Allen and Charles White. John Jr. would choose to pursue football, too, spending a few seasons in the NFL with the Phoenix Cardinals and Chicago Bears. He caught nine career passes and spent the rest of his life wondering what he could have done in baseball.

John III had wanted to be a baseball player, too. But by the time he was a senior at Serra in 2017, he had switched from quarterback to wide receiver and emerged as a three-star prospect. USC coach Clay Helton was recruiting him but not intensely since the Trojans already had blue-chip receivers Amon-ra St. Brown and Devon Williams lined up.

Given that Major League Baseball scouts had their eyes on his son, John Jr. just couldn’t see it. One day, John III wanted his dad to take him to a seven-on-seven practice, and John Jr. told his son to forget about football and to go hit.

“Dad, what do you think, I can’t make it?” John III asked him. “What do you think? I’m not good enough?”

“It really hurt my heart,” John Jr. would say. “That was shocking, because it sort of hit me like, you know what, this is his life, not my own. If it was my choice, he never would have picked up a football. But if my kid is questioning my confidence in him, then I’ve got to back off.”

USC football was such a part of John III that it wasn’t really a choice. Plus, John III enjoyed how much more attention he got for playing football — he was overjoyed when his Instagram followers jumped to 1,000 — and there was nothing like a packed Coliseum.

“He went on a recruiting trip,” Ann-Frances Jackson recalled, “he walked into the stadium and looked around, and I said, ‘What do you think?’ And he said, ‘Mom, how could you say no to all of this?’ ”

Helton wasn’t exactly offering him the keys to the kingdom, though. John III’s scholarship was contingent on him taking a grey-shirt year, postponing his enrollment into USC until the second semester and joining the team as a freshman then. He would quite literally be an afterthought, forced to take classes in the fall at a junior college, and yet, as scouts pushed for him to choose baseball up until the June draft, John III told them not to use a selection on him.

Now it was December, almost time for John III to finally live his dream, and he could not hear his dad’s advice. He kept writing those letters through the holidays, sleeping next to his dad many nights in a small chair in the hospital room, begging him to wake up. They looked for any sign he was still in there, squeezing his hand, hoping for the faintest touch in return.

John III had always relished the thought of his dad calling one of his USC games from the booth. With him unable to speak, that vision felt too far off.

Early one morning in late December, about 1:45, John Jr. woke. John III and his aunt happened to be awake, too. His father knew sign language, and he was trying to say something with his right hand. Frantically, they searched Google for the meaning. After 10 minutes, they had it.

John Jr. was signaling “JJ3.”

::

Once it became clear that John Jackson III was going to attend USC, his dad would joke with him that he would walk him to class in the mornings.

“Just like you were in elementary,” John Jr. would say, “hold your hand, give you a kiss good-bye!”

John III would brush off his cantankerous dad, but this winter, as he contemplated a life without him, he was more than open to any fatherly embarrassment John Jr. could bring.

On the day of the stroke, John III heard the news and figured his dad would be down for a day or two and back at it. This was the guy who once took a baseball to the face, losing a tooth, and kept on leading his son’s practice like it was nothing. But seeing John Jr. laid out unconscious and attached to ventilator tubes, day after day, resonated.

Then there was their conversation before the January surgery.

“It allowed me to realize that, although I’m kind of in my own little zone, I have a family that’s looking up to me and looking for me to fill holes that my dad usually takes care of,” John III said.

John Jr. came out of that surgery just fine. In the weeks that followed, a bandage covered the hole in his head, and Ann-Frances could not get over the doctors appearing nonchalant about a part of his skull being embedded in his stomach. They would compare the swelling in his brain to a swollen ankle. In both cases, you just had to wait it out. Eventually, another surgery was performed to put the skull back together. That one went as planned, too.

Still, John Jr. had a long road ahead. His left side was left nearly paralyzed from the stroke, and he would have to relearn how to walk. His speech came back slowly. In all ways, his family had to protect him, encouraging him to pace himself even though they just wanted him back whole.

John III focused on what his dad had told him. He started classes in the real estate program and started looking for summer internships, too. Waking up at 5:30 a.m. to work out became normal, as he pushed to increase his speed to catch up as an attribute to his size, 6 feet 2, 200 pounds. As January became February, John Jr. could keep better tabs, and he liked what he was hearing.

“That was a lot of weight for me to put on his shoulders,” John Jr. said, “but he didn’t waver. He didn’t say, ‘No, that’s not for me. You better find somebody else.’ I couldn’t be prouder of him for that.”

On March 5, USC staged its first spring practice. John Jr. couldn’t be there to see it, and the reality was he probably wouldn’t be able to see him in that cardinal practice jersey until August. But that didn’t take anything away from the moment for John III. After all, this was his dream, and he had dragged his father along into it with him.

John III slipped on the uniform for the first time and took stock of himself in the mirror.

“It was a dream come true,” John III said.

He wore No. 87, not the No. 1 that his father donned as a Trojan. He could have asked for No. 1 from Helton, but John III had a calculated reason for staying quiet. His dad wore No. 29 during his first year on campus before asking for No. 1.

“I want it to be one of those things where it’s earned,” John III said. “Honestly, this is an unfortunate situation, but I don’t want to use this as a reason to get No. 1. I want to get it the same way any other kid would get it, through my play, rather than it just being given to me because of who wore it before me.”

::

More than four months have passed since paramedics wheeled John Jackson Jr. through the doors of this hospital, and the mood feels lighter today in the lobby of the transitional care unit of Torrance Memorial. His partner in the Coliseum booth, play-by-play man Arbogast, has stopped by for his weekly visit.

John Jr.’s mind has been active for the past hour, working at peak efficiency when discussing the past, particularly his son’s journey. His body is coming along, too, and he shows it by moving his left foot in the wheelchair.

“I haven’t seen that yet,” Arbogast says.

John Jr. then twitches the fingers on his left hand.

“I haven’t seen that either!” Arbogast says.

“If your stroke had hit the other side of your brain,” Arbogast reminds him, “you wouldn’t be able to talk and reason and all that stuff.”

“How lucky I am,” John Jr. deadpans.

He can’t remember anything that happened between the stroke and his birthday, Jan. 2. Everything that came after has been a never-ending grind.

“When I started, I was counting the tiles on the ceiling,” John Jr. says. “When I first went 10 tiles, that was a big thing. Then, I walked 33 tiles, and that was my record. The trainers are good. They’ll say, ‘Wow, I remember when you were only doing two tiles.’ ”

With the help of a walker, John can make one lap around the TCU. A week after this April 10 visit, he will be moved to an acute rehabilitation center, the first big step toward an existence that includes regular trips to USC to watch his son play football.

Arbogast and many other Trojans continue to keep him apprised of his son’s progress on the field. John III even brought film with him to the hospital, inviting his dad’s coaching. Because of a lack of depth at his position, John III worked immediately with the second team, but Helton’s comments to media early in camp indicated he was worthy of the work.

The most important thing was that John III felt that way, too. He proved to himself that he belonged on the same field as St. Brown, Michael Pittman Jr. and Tyler Vaughns.

“After he had a few good practices,” John Jr. says, “he came in and he said, ‘Dad, we did it.’ ”

He fights back tears.

“I’ll never forget that,” he says. “Every drive to Rancho Cucamonga for seven-on-seven where I’m falling asleep was worth it. It was all worth it to hear that one sentence that he said to me.”

The letters the son wrote to his father remain stacked at John Jr.’s bedside, unread because reading is still too much of a chore. Someday Dad will read them, and he will further understand that John III did not choose football over baseball.

“It was USC football,” John III explained. “It’s something about it. I get goosebumps being in the locker room. I’m in love with USC.”

That love was always shared between them. Now, the USC football dream is theirs, too.

“When I first came out of this and I couldn’t move, I said, ‘I don’t care what happens. I will be at the Coliseum to watch him run out of the tunnel,’ ” John Jr. says. “Half the time when I’m working out, that’s all I think about. It makes it a lot easier to get up for workouts at 7:30 in the morning, because it’s the only way I’m going to be able to get to that Coliseum for Game 1.”

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

Twitter: @BradyMcCollough

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.