Sineeka Latimer said she has vacillated between tears and prayer since she learned late last month that she was being evicted from her home in Greenville, South Carolina, where she lives with her four teenagers and her mother.

After two murders near her rental home, Latimer, 40, wanted a safer place for her family to live. Unable to find an affordable new home, however, she began her application to renew her lease. With many offices closed or unable to serve her in person, the coronavirus pandemic complicated her ability to collect all the documents she needed and pay her rent in time. She got an eviction notice days later.

Now Latimer — who works at an assisted living facility for $12 an hour — her mom and her kids have to leave their home Monday with no idea where they might next rest their heads.

"Cost of living here is just so high," said Latimer, who has gone through a period of homelessness before. "We're probably going to have to put our stuff in storage and go to a motel until something comes through."

Latimer is one of thousands of people who face or will face eviction as the economic recession caused by the coronavirus pandemic has led millions across the United States to find their housing situations complicated or to miss their housing payments. Latimer's eviction is part of the early wave that came after the state moratorium was lifted in May.

The federal moratorium, which Democrats and Republicans in Congress continue to debate in the latest negotiations over coronavirus legislation, paused evictions in most federally subsidized housing for four months, affecting 12.3 million to 19.9 million households. The eviction notices for those homes in South Carolina and other states will go out Aug. 24, because the federal moratorium expired at the end of July.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Before the pandemic, South Carolina already faced a long-term housing crisis, and it had the highest eviction rate in the U.S., nearly twice that of any other state, according to Princeton University's Eviction Lab. Now, with tens of millions in the United States out of work and the sudden disappearance of the unemployment relief and eviction moratoriums provided by the expired CARES Act, the pain caused by the pandemic could reach a whole new dimension.

In South Carolina alone, 52 percent of renter households can't pay their rent and are at risk of eviction, according to an analysis of census data by the consulting firm Stout Risius Ross. About 185,000 evictions could be filed in the state over the next four months.

Rental assistance needs will grow to nearly $835 million to cover those at risk in South Carolina this year, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

The situation isn't much better in the rest of the country: 40 percent or more of the renters in 29 states could face eviction because of the recession triggered by the pandemic.

"A lot of the safety net things that people relied on are gone," said John Pollock, coordinator of the National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel, which assisted Stout Risius Ross in its data analysis. "And some of the things that they relied on, like credit cards and borrowing from family, those are not sustainable ways to pay rent. So as bad as the numbers have been up to now, it pales in comparison to what's coming. If Congress does not act and provide substantial relief, we're going to go over the cliff."

'Preparing for a tsunami'

Janice "Pinky" Whitney, 64, is used to taking care of others, cooking large batches of soul food in her kitchen four days a week for the people experiencing homelessness in the neighborhood. She makes only about $500 a month through her Supplemental Security Income, and a local church helped her pay her rent. But she was recently forced out of her home in Greenville because the landlord deemed it uninhabitable at the end of June, and she has slept in her car with her dog or in a nearby motel since then.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

Now she is the one in need, as she has gone without food and doesn't know how she will find another home during a pandemic. She sobbed over the phone as she reflected on her situation.

"I hurt for them when I don't have food and I can't feed them, but now my stomach is growling. It really made me appreciate the love that I showed them," she said of the people she fed. "It ain't no fun when your stomach hurts from hunger. It ain't no fun — especially in a pandemic."

Hunger is a real side effect of the housing crisis.

Thirty-two percent of South Carolina households struggle to afford basic needs, such as food, clothing and transportation, because of high housing costs, according to the South Carolina Housing Needs Assessment published in August 2019.

The state has few tenant rights, and filing for eviction is comparatively easy — it requires five days' notice and a $50 fee. As a result, South Carolina averaged 400 to 500 evictions a day from 2015 to 2019.

After the state's temporary eviction and foreclosure moratorium, which was issued by state Supreme Court Justice Donald Beatty, expired in May, landlords began filing eviction notices for the rent they missed in March and April.

The number of eviction notices filed in April jumped from 40 to more than 4,500 in May and over 6,000 in June, according to court records. Advocates say the number of evictions will return to the level before the pandemic soon — there were more than 162,000 eviction filings in South Carolina last year — and they are bracing themselves for it to become much worse, as the state economy hasn't rebounded and the few safety nets protecting people have been removed.

"Particularly because of COVID, we are preparing for a tsunami of folks," said Lorain Crowl, executive director of United Housing Connections, a South Carolina housing aid organization. "You know, not just in the lower-middle-income or low- to middle-income areas, but in the higher income brackets, and we're left wondering how that's going to affect our system. Six months from now is what I'm really worried about."

Few solutions on the horizon

Advocates say that there needs to be another moratorium but that Congress also needs to go further and provide rental relief funds and access to counsel to help those who face eviction. Neither is being considered by Congress, but many emphasize the need for rental relief, because the moratorium will only prolong the inevitable due date for rent, as unpaid obligations rose to more than $21.5 billion nationally.

Those who face eviction in South Carolina and those advocating in their behalf don't have a lot of faith in the state government's filling those shortfalls, however.

The court system — in the form of about 300 state court magistrates who are left to oversee eviction filings — don't provide a heartening avenue, either.

The magistrates, who are appointed by the governor, don't need law degrees or to pass the state bar to take on the role. They must only pass certification examinations within a year of their appointments. While nearly half the cases were settled in 2019, according to South Carolina court documents, magistrates sided with landlords more than 44,000 times last year — about 27 percent of the time.

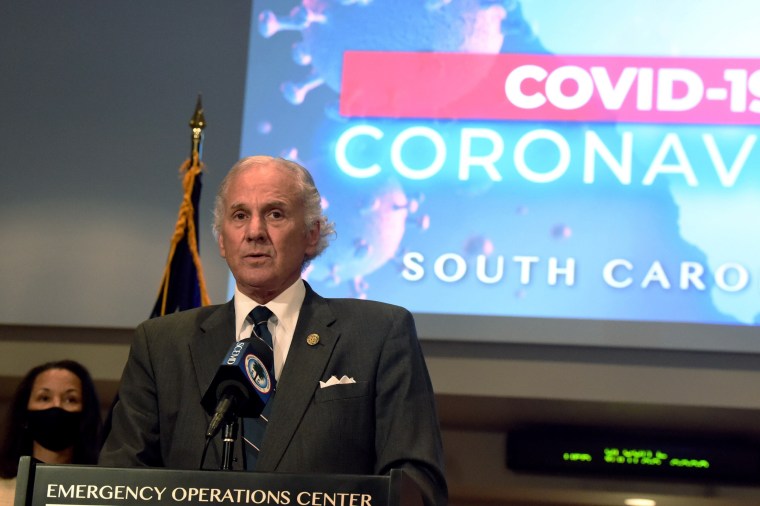

Meanwhile, Gov. Henry McMaster, who didn't respond to a request for comment, is a landlord himself, and he has continued to collect rent throughout the crisis, according to The Post and Courier newspaper of Charleston. He collected nearly $1.3 million in rent in 2018 from his 200 or so tenants, the paper reported.

State Rep. Marvin Pendarvis, a Democrat who represents North Charleston, introduced a bill that would extend the moratorium and provide rental assistance, and he hopes to have the state reconsider the magistrate system. But he admitted that his bill is unlikely to pass or to even be considered.

While he said he likes his Republican colleagues personally, the political realities of their party majority — as they push to reopen the economy and stand opposed to government spending — limit the state's ability to put a safety net in place to help tenants.

"The moratorium wasn't something that we did as a legislature, and the governor didn't do that, either — everyone punted," he said. "We went to the state Supreme Court to make the call. That's the kind of the mindset that's here in South Carolina, so I'm not optimistic."

But even some landlords argue that the state needs to consider rental assistance.

Jaymes McCloud runs a property management company. He said he worked out payment plans with many of his tenants rather than file eviction notices, but he said the moratorium drained his company's resources so much that it struggled to make repairs, forcing it to turn to a nonprofit to help replace an air-conditioning unit a tenant needed fixed.

"People don't want to move. I don't want them to move. There are a handful of slumlords here who are doing a disservice to people, but we were able to create some payment plan incentives and programs for people to keep them in their units," he said. "You got to meet people where they are at. People can't get back to work, so to be honest with you, it's just a matter of rental assistance."

Support services, such as the homeless shelter One80 Place in Charleston, are preparing for the long haul. But as Marco Corona, the shelter's chief development officer, said, the next few months aren't the worry. It's maintaining the new threshold of support six months from now and beyond.

Corona said that the shelter is providing millions of dollars in housing relief to its 800 to 1,000 clients but that it's just a drop in the bucket of the greater need across the state.

"We're seeing this as the new normal for at least the next year, possibly 18 months," he said. "We're increasing our capacity and our bandwidth in preparation for the additional services and clients that we've never seen before."

'The Scarlet E'

Jennifer Taylor, 34, has seen how an eviction can change your life. She said she has spent the last 14 months experiencing homelessness after a disagreement with an ex-boyfriend caused her and her son to be evicted from their home of 12 years.

Her son, Gage, 12, has been with her for the past eight months as they have slept in parks and shelters — always hoping to find some kind of break. They're on the cusp of finding a home in Columbia through the help of a shelter.

Taylor said she had no idea that an eviction on your record could derail your life, but it forced her and her son to live through the hardest period of their lives during a pandemic. Most landlords consider what many call the "Scarlet E" an automatic denial to prospective renters.

"As soon as you mention an eviction, they won't even run your credit," she said from the shelter she and her son are living in. "Nobody even talks to you."

That's a situation millions of Americans could face with evictions on the horizon. Although many may ultimately be able to remain in their homes, with the "Scarlet E" on their records there could be a massive downstream economic impact.

"It's hard to conceive of how dramatic the effects will be," said Bryan Grady, the chief research officer of SC Housing, the state housing authority. "Not immediately, but obviously once people have an eviction on their record, that substantially compromises their ability to find housing in the future — even if they find a job and the economy finally recovers."

While millions across the country are under threat, Sineeka Latimer and her family only have the ability to think about Monday — the day they'll have to be out of their home permanently. Whether they'll be able to find housing in the near future is a challenge for another day.

"I have children trying to be prepared for school," Latimer said. "It's just a mess, and I just get overwhelmed. I have to do all this stuff. I'm a single mama of four teenagers and trying to take care of my mama. I just cry if I have to and ask God to give me strength."