Louisiana’s prison system and local jails, including the Orleans Justice Center, routinely keep people locked up for weeks, months, some even years, after they are supposed to be released, according to a 2017 state auditor’s report, defense attorneys and former inmates.

Hundreds, and possibly thousands of people, have been affected. Every week over the last decade, prison staff found at least one person who had been kept in jail or prison longer than their sentence required, court records show. One state inmate was imprisoned 960 days, almost three years, past his official release date.

Civil rights lawyers, in response, have filed multiple lawsuits against the Louisiana Department of Corrections or the Orleans Parish Sheriff's Office, several of which resulted in hefty settlements paid by tax dollars. Officials have known of this problem for years but failed to correct it, the attorneys allege.

These injustices could be fixed, criminal justice experts said, if only state and local authorities would improve coordination. What officials appear to have done, instead, is blame each other: The sheriff’s office denied responsibility when reached for comment, blaming the Department of Corrections (DOC). DOC declined to comment citing pending litigation, but in court transcripts it has pointed the finger at the sheriff’s office.

The end result is a decades-old problem that damages lives and costs taxpayers millions of dollars.

"The criminal justice system is based on the idea that if you do a crime you serve your time and then you go free. And that going free part is not being carried out correctly in Louisiana," said civil rights attorney William Most, who has lawsuits pending against DOC and local sheriff's offices related to the alleged overdetention of five different clients.

“It’s hard to be in prison. But it’s even harder to be in prison knowing that you should be free and not having any idea when you’re going to get out,” Most said.

Johnny Traweek, who was overdetained for 22 days after he pleaded guilty to second-degree battery, filed a lawsuit against Orleans Parish Sheriff Marlin Gusman. (Photo by Brett Duke, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

48 hours turn into weeks and months

Johnny Traweek decided to plead guilty to second-degree battery in 2018. The 66-year-old retiree didn’t agree with the charge, but, due to his inability to afford bail, he had already spent seven months in New Orleans jail waiting for his day in court. There was a good chance, he thought, that his sentence would match or come in under that number.

If Traweek was right, he’d likely be credited for time-served and immediately released. If he was wrong, he could face up to five years in prison.

On May 2, Traweek listened anxiously as an Orleans Criminal District Court judge read his sentence: Seven months. Credit for time served.

The gamble had paid off.

In the hours afterward, Traweek said, he was on “pins and needles,” waiting to hear a deputy call his name to be processed out of the Orleans Justice Center jail. The first thing he planned to do, he said, was to head to the Moonwalk along the Mississippi River.

But no one called his name, not that day or the next.

Traweek asked the deputies why he was still locked up. “Man, check my record,” he’d tell them.

But Traweek didn’t get answers. It didn’t make sense. He had served his time. The judge had said so. It was all in the court record. Why was he still in jail?

Traweek’s case, and others like his, hinge on a single legal question and a recurring problem in Louisiana: does the sheriff’s office or the Department of Corrections have the right to keep someone imprisoned past their scheduled release date for any reason, and if so, how long?

The federal 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2011 ruled that it's “clearly established law that a prison official must ensure an inmate’s timely release from prison” once the sentence has expired. That “timely release” has been defined as less than 48 hours.

In 2005, a federal district court judge in Atlanta wrote she had been “unable to find any case... in which the detainment of a properly identified individual for days beyond his scheduled release date was held constitutionally permissible.”

That judge, Julie E. Carnes, who is now the Senior U.S. Circuit Judge in the 11th Circuit’s Court of Appeal, made the statement as part of a ruling on litigation by jailed people in Atlanta who sued a sheriff and the State of Georgia. The plaintiffs in that case had been overdetained by an average 3.9 days, court records show.

New Orleans public defender Stanislav Moroz in his office on Thursday, February 14, 2019. Moroz said he and his colleagues identified at least 46 cases of possible overdetention in 2018. (Photo by Brett Duke, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

Despite those rulings, the Louisiana Department of Corrections appears to give itself in many cases anywhere from a few weeks to several months to process and release inmates. When New Orleans public defender Stanislav Moroz contacted the sheriff's office to ask why Traweek was still in jail seven days after he was sentenced to time-served, OPSO employee Monique Filmore wrote back, "First of all Johnny Traweek was just sentenced on 5/2/18 so his paperwork has not went up yet."

When Moroz checked in with OPSO five days later, Filmore reasponded, "He can't get released until DOC sends him a release. The whole process takes about 2 weeks. He has to wait!!!!"

Meanwhile, an outgoing message on a DOC hotline states that "it takes at least 90 days after sentencing" for the department to calculate how much time a person must serve of their sentence. Only after this step is completed will DOC issue an official release date.

Waiting a few weeks or months might not be a problem for someone sentenced to years in prison, but it is for people like Traweek who have already served their time yet remain behind bars, Moroz said.

"We certainly don't think it's right or perhaps even legal, but it's part of what we expect to happen," Moroz said. "So, while it's extremely unfair and should be unconstitutional based on similar lines of jurisprudence, DOC gives themselves a lot of time to calculate when people are eligible to be released. That's their policy."

Moroz, who has been tasked by the Orleans Public Defender's Office with tracking how often people are being held past their release dates, said between Jan. 11 and Nov. 4, 2018, attorneys in the office reported 46 people who may have been overdetained.

As for Traweek, he was eventually released 22 days after his sentencing hearing with Moroz' intervention. During his extra time in jail, Traweek said, no one could "be bothered" to listen to or act on his concerns "because your life means nothing to them."

On Feb. 14, Most filed a lawsuit on Traweek's behalf against Orleans Parish Sheriff Marlin Gusman, Filmore and other unnamed people at the sheriff's office. He cited 14 other cases of overdetention in New Orleans, though he emphasized it is a statewide problem.

The state's Elayn Hunt Correctional Center in St. Gabriel on September 7, 2018. (Photo by Brett Duke, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

Clerical errors add years in prison

A 2017 state auditor's report on how DOC manages inmate data blasted the department as being incapable of calculating in an accurate and consistent manner how much time people should spend in prison and when they should be released.

For example, the auditor asked two DOC staffers to “calculate release dates on the same offender, and each used a different method. The two results differed by 186 days.” That would be a difference of about six months more in prison.

The haphazard manner in which DOC calculates time is one of the main drivers of overdetention and has resulted in multiple lawsuits, two of which the department recently settled for a total $250,000, records show.

The first involved Shreveport resident Kenneth Owens, who in 1989 was sentenced to 21 years for attempted manslaughter. Owens should have earned 30 days of good time credit for every 30 days served, putting his release date on Jan. 4, 2004. DOC, however, awarded him only 15 days for every 30 days served and, as a result, didn’t release him until June 14, 2007. The Department of Corrections settled Owens’ lawsuit in November 2016 for $130,000.

The second lawsuit involved James Chowns, who in 2002 pleaded guilty in Ouachita Parish to two counts of aggravated incest. The judge sentenced him to five years in prison followed by 10 years of probation. But based on a clerical error, DOC incorrectly determined Chowns was to serve 10 years in prison. The courts ruled in Chowns’ favor, finding that he was overdetained for 960 days. DOC settled the case in May 2018 for $120,000.

DOC attorney Jonathan Vining said in a Feb. 20 interview the department was not to blame in the Owens case. He said the case involved a dispute over earned good-time credits, and DOC maintains it applied the law correctly. “It was not an error, nobody made a mistake,” Vining said. He also said the department opposed a state settlement with Chowns and does not accept blame for the extra time Chowns spent incarcerated. The judge in the case made the error, not DOC, Vining said. Once the judge fixed the error, “within a day of (receiving) the paperwork, we released the man," he said. Vining called the settlement payout, "a waste of taxpayer dollars."

During testimony in Chowns’ lawsuit, however, DOC employees said over the previous nine years they had discovered approximately one case of overdetention per week, and that it is not uncommon for inmates to be held more than a year past their release date. Another DOC employee testified that he discovered “one or two” inmates a week who were eligible for immediate release.

Shreveport attorney Nelson Cameron, who represented Owens and Chowns, acknowledged that many people might not care if someone convicted of attempted manslaughter or aggravated incest is held long past his release date. But they should, he said, because it strikes at the very core of the nation’s legal system.

“When a court sentences somebody, you have a debt that has to be paid just like if you have a debt with the bank,” Cameron said. “It would not be right if you went to the bank after paying your loan off and they demanded you pay 50 percent more.”

If people don’t care about the injustice of it, Cameron said, maybe they’ll be concerned about the money wasted incarcerating two men long past their lawful release dates. The state overdetained Owens and Chowns a combined 2,216 days. At an average cost of $54.20 per day to house an inmate, that’s an extra $120,107 taxpayers spent – not including the court settlements that came later.

“It’s not just these two guys,” Cameron said. “It’s widespread.”

Elayn Hunt Correctional Center in St. Gabriel on September 7, 2018. (Photo by Brett Duke, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

DOC secretary defends staff

In DOC’s official response to the legislative audit, Secretary James LeBlanc defended his staff, writing that the calculation of releases dates is a “very complex and ever changing” process that considers up to 20 different criteria. It is complicated even further, he said, by the Legislature passing new laws every year – such as 2017’s historic criminal justice reform package – which drastically alter the sentencing guidelines.

“Training for this job is ongoing and takes time to truly understand the intricacies of how each case is handled,” LeBlanc wrote. “Time computation staff are expected to know all laws, old and new.”

That same staff consists largely of people in entry-level jobs who collectively work on an average of 4,213 files per month, according to DOC. The staff’s turnover rate in 2017 was 33 percent. It dropped to an still-high 21 percent last year.

The legislative auditor recommended a number of potential solutions to fix DOC’s overdetention problem, including replacing the department’s data system – the Criminal and Justice Unified Network, or CAJUN – which has been in use since the 1980s. The system has long been plagued by inaccurate and incomplete record-keeping, which can impact the calculation of release dates, according to the report.

Corrections previously attempted to replace CAJUN in 2015. It invested $3.6 million in a new data system that went live in June of that year but was taken down 46 days later because DOC didn’t properly test it or train staff in its use, the auditor wrote.

In October 2017, the state paid third-party contractor Sirius Computer Solutions $49,000 to determine if the new system could be salvaged. Sirius concluded it could not. DOC spokesman Ken Pastorick said they are working on a new replacement system, though he did not provide a date when it might be online.

In addition to their attempts to replace CAJUN, LeBlanc wrote that DOC was working on a new training manual for the time computation staff. More than a year later, that manual remains unfinished.

“While not fully completed, we anticipate completion in the near future,” Pastorick said.

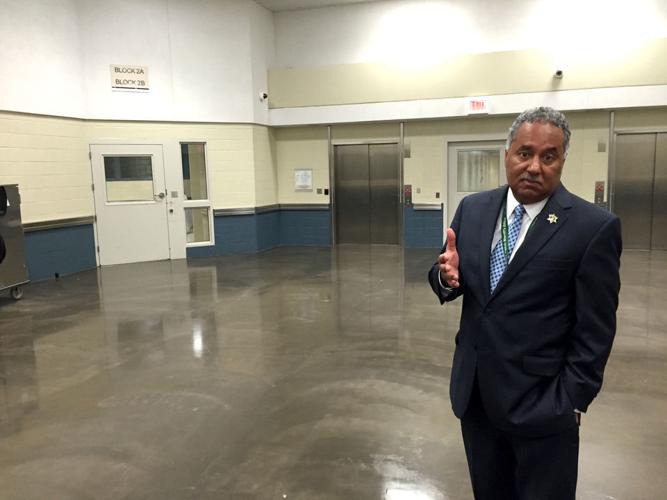

Orleans Parish Sheriff Marlin Gusman stands inside the Orleans Justice Center on May 2, 2016. (NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

Even a judge's pleas weren't enough

These proposed solutions, however, would not prevent all cases of overdetention, such as Rodney Grant’s.

In the summer of 2016, Grant was trying to put his life back together, having just finished a 7-year sentence for simple burglary and unauthorized entry of an inhabited dwelling. He had managed to secure an apartment and a job. Things were looking up. But when he tried to obtain a driver’s license in June of that year, he was arrested on a 16-year-old warrant for simple burglary.

Grant pleaded guilty before Criminal District Court Judge Camille Buras on June 30, 2016. Buras sentenced him to one year in DOC custody with credit for the seven years he had just spent in prison. That same day, Buras contacted Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office attorney Blake Arcuri to request they expedite Grant’s release. Arcuri relayed that request to Sheriff Marlin Gusman and others, writing that Grant “really shouldn’t have to actually serve any time,” court records show.

Instead of expediting Grant’s release, however, the sheriff’s office followed a bureaucratic process dictated, it contends, by DOC, that had Grant shipped from New Orleans’ jail to the state’s Elayn Hunt Correctional Center in St. Gabriel, and then to Madison Parish Correctional Center in Tallulah, 244 miles away. The sheriff’s office did so, Most wrote in a subsequent lawsuit, fully aware that Grant had already served his time and knowingly violating his constitutional rights.

“The sheriff’s department has a policy of holding inmates in custody – regardless of whether they should be free – until the Department of Corrections says,” Most wrote. “As a result, there is a whole class of people who are regularly and automatically being overdetained by OPSO policy.”

Attorney William Most has lawsuits pending against DOC and local sheriff's offices related to the alleged overdetention of five different clients. Photographed Friday, February 15. 2018. (Photo by Brett Duke, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

The sheriff’s office claims its hands are tied. Once a judge sentences someone to DOC custody, even if in the next breath the judge credits the person for time served, the sheriff’s office no longer has authority over that inmate, an OPSO spokesman wrote in a statement for this story. The only way they could free such a person is if DOC orders their release.

To get such a release, the sheriff’s office first must send the inmate’s paperwork to the department of corrections. But it doesn’t do so electronically. Once a week, every Thursday, an OPSO employee actually drives 68 miles to the Elayn Hunt Correctional Center in St. Gabriel to hand-deliver that week’s paperwork. The sheriff’s office then holds the inmate indefinitely until it hears back from DOC. For Grant, this took 13 days.

The sheriff’s spokesman agreed that physically transporting paperwork is not the most efficient method and advocated for an electronic transmission of records.

“Such a system would allow local jails to enter local time served, as well as scanned court documents, and thereafter allow DOC to simply approve computer-run calculations and hold checks, instantly issuing a release or transport order,” the sheriff’s office said.

In Grant’s case, DOC requested the sheriff’s office transport him to Hunt Correctional Center, so that‘s what they did, despite the judge’s request for a fast release.

When Grant arrived at St. Gabriel prison on July 12, 2016, DOC, in keeping with its 90-day policy, still had not calculated his time, which would have alerted officials that he was not supposed to be incarcerated. As a result, they treated him like a long-term inmate and sent him to the Madison Correctional Center in Tallulah, which is operated by LaSalle Corrections, a private prison corporation.

“At intake there, Rodney explained to an officer that his time was served,” Most wrote in the lawsuit. “She looked at his sheet and agreed that it indicated ‘no sentence.’ However, LaSalle did not release Rodney.”

Around this same time, a concerned friend contacted Buras to say that Grant was still incarcerated. The judge called Gusman and the Madison warden to alert them about the situation, but nothing happened. She then held a hearing July 18 – more than two weeks after she had asked for a quick release for Grant – in which she vacated the sentence and replaced it with “credit for time served.” DOC and LaSalle still did not release him.

Buras made one final round of calls to DOC officials July 25. Two days later, and 27 days after he was sentenced to time served, LaSalle officials finally released Grant. They dropped him off in Madison Parish with a bus ticket back to New Orleans.

Orleans Parish Sheriff Marlin Gusman speaks to inmates May 2, 2016, inside the Orleans Justice Center. (NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

'It's about holding public actors accountable'

Emily Washington, an attorney with the Roderick & Solange MacArthur Justice Center, said these cases aren’t about “mere paperwork and bureaucracy. It’s about holding public actors accountable. And it’s about the value we place on liberty, whether that is a day, a week, or months in someone’s life.”

The MacArthur Justice Center filed a lawsuit in 2017 against DOC and the sheriff's offices in Orleans and East Caroll parishes, alleging five men were separately overdetained between three and five months in late 2016 and into 2017, after being sentenced in New Orleans.

In reference to two of those men who had been kept at the Orleans Justice Center, the Orleans sheriff’s office responded to the suit saying it was not responsible for their overdetention because the Department of Corrections hadn’t issued a release, according to a Sept. 18, 2018, hearing transcript. Corrections argued it wasn’t responsible either, saying it didn’t get the necessary records from OPSO about pretrial credit to process it.

Washington argued that the fault lay with both agencies.

“They all have responsibilities to make sure that they were not holding people in custody without valid legal authority,” she said, according to the court transcript. “That’s the constitutional right we are talking about.”

U.S. District Judge Shelly Dick, who is presiding over the litigation, summarized the suit’s allegations at the hearing like this: “The crux of the plaintiffs’ allegations are that the defendants have either deficient or nonexistent policies for processing and releasing DOC inmates who are ultimately sentenced.”

Dick denied the motions by DOC and the sheriff’s office to dismiss claims, giving the litigation the go-ahead to move forward. The lawsuit is ongoing.