A fight is brewing between preservationists and a growing number of developers looking to build hotels in a historic enclave of the Central Business District.

The Lafayette Square Historic District, which covers a swath of the CBD just upriver from Poydras Street, is one of the city's oldest residential districts and has been a hot property market over the past decade. In the past four years alone, hundreds of apartments and condominiums have been built there, and several large projects are still underway.

It is uniquely situated in the middle of the city's main attractions, within walking distance of the French Quarter, the museum district, Morial Convention Center, Mercedes-Benz Superdome and Smoothie King Center.

With its mixture of Federalist and Greek Revival architecture styles — highlighted by Gallier Hall, New Orleans' antebellum seat of government — the neighborhood also has been recognized for its historic significance and has special protected status under city rules.

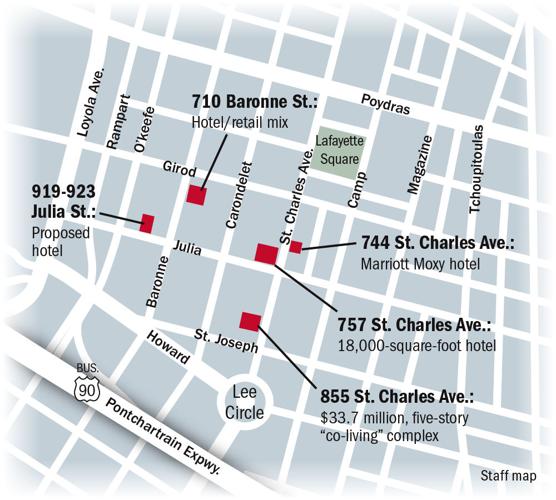

PROPOSED HOTEL DEVELOPMENTS: Local preservationists fear these developments will change the character of the historic Lafayette Square area.

Now, neighborhood activists are worried that too much residential supply, coupled with tighter zoning rules that will sharply limit short-term rentals in much of New Orleans, means developers will target their slice of the city to build hotels — turning it into yet another teeming tourist precinct.

Recently proposed projects include the revival of a Marriott Moxy Hotel on St. Charles Avenue, which had previously been permitted by the City Council. Another smaller hotel is proposed for a site directly across the street on the corner of Julia Street. And the owners of 923 Julia St. and 710 Baronne St. are looking for permission to change their proposed projects from residential to hotels.

923 Julia Street, a development by Chris Sarpy, Brian Gibbs and Andy Solomon, has morphed into a hotel proposal from an original mixed-use, residential/retail project.

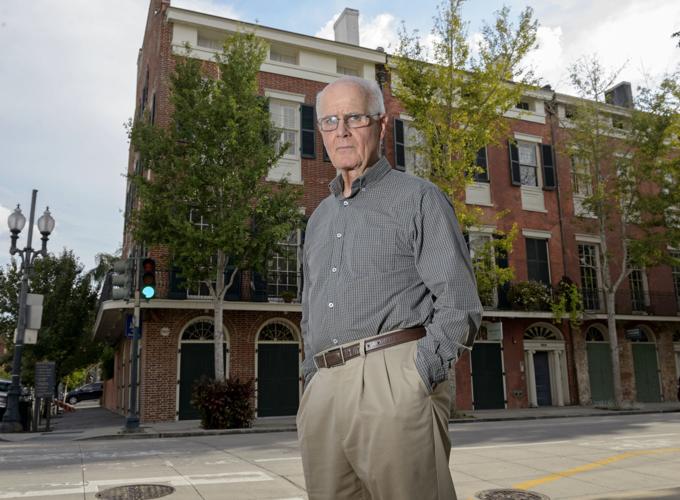

Michael Duplantier, the president of the Lafayette Square Association, said his group has stood by as more and more tourists have discovered the area, drawn by restaurants, new hotels and the ever-expanding National World War II Museum nearby.

The 234-room Ace Hotel, an award-winning renovation of a 1928 Art Deco building on Carondelet Street, opened in 2016. Also, Virgin Hotels, which took years to win city approval, finally broke ground in May on its $80 million, 230-room project at Baronne and Lafayette streets.

Construction for the 14-story Virgin Hotel at the corner of Baronne and Lafayette streets in downtown New Orleans on Tuesday, August 20, 2019.

"We decided to draw a line in the sand at the start of the year," said Duplantier, who took over in January as head of the group founded by neighborhood residents in 1976 to resist the spread of office skyscrapers then starting to dominate the CBD. "We just don't want to become a tourist neighborhood and everything that comes with that."

A decade after post-Katrina planning czar Ed Blakely predicted cranes soon would be visible on the New Orleans horizon, they’ve finally arrive…

The spat echoes others waged in neighborhoods across the city, including parts of the Garden District, Marigny and Bywater, where residents and business people have been at loggerheads over what constitutes the right balance between residents' rights and economic development.

The City Council has often played referee, and zoning laws enacted four years ago make it especially hard for developers to get permission to build a hotel in the Lafayette Square sector of the CBD.

Kathleen Lunn, a real estate broker who is the chairwoman of the City Planning Commission, which advises the City Council on zoning issues, was the only member of the panel to oppose a plan by developers Christopher Sarpy, Brian Gibbs and Sam Solomon to change their 923 Julia St. project from residential to a hotel.

For years, rising tourism in New Orleans has driven a downtown construction boom, thanks in part to generous tax credits that have made it pro…

Lunn said she's not against commercial developments in the area. "But I felt it didn't offer enough as a hotel compared to a multifamily dwelling," she said, primarily because there isn't enough frontage at the site — currently a parking lot next to a motorcycle shop — to allow anything more than a wall and garage entrance for a hotel. The project will go to the City Council in October without a commission recommendation.

Tighter rules?

Sarpy said he doesn't understand the rationale. He said his planned 40-unit apartment complex had the full support of the neighborhood, but the exact same design for a hotel does not. In fact, he sees no good reason why there should be tighter rules for hotels in this area than in any other part of the CBD.

"They want it to be apartments or a family residence or nothing," Sarpy said, noting that apartments likely would be 90% full at any given time, while hotel occupancy would be closer to 70%. "Is that a reasonable distinction to make as far as the neighborhood is concerned? I don't think so."

Also sparking controversy is a proposed conversion of 757 St. Charles Ave., currently home to Blitch Knevel Architects and a small block of offices for professional firms, into an 18,000-square-foot hotel.

757 St. Charles Avenue, formerly occupied by offices of architecture firm Blitch Knevel, as well as various law firms, is being converted to The Perle Hotel, an 11-suite "large format" operation aimed at renting to large groups.

A company owned by Keith Hardie, a lawyer who has been a high-profile activist himself on various New Orleans historic landmark and neighborhood boards, and Kenneth Knevel, the architect, are proposing to build a hotel with up to nine suites, varying in size from three to five bedrooms, in the three-story building at Julia Street and St. Charles Avenue.

"It sounds like a flophouse to me," said Cassandra Sharpe, a member of the Lafayette Square Association board.

Sharpe owns one of the "thirteen sisters of Julia Street," a nationally recognized row of townhouses along Julia from St. Charles to Camp Street that date from the early 1830s.

Their renovation by preservationists in the 1970s, coinciding with the opening of the Contemporary Arts Center on Camp Street, marked the beginning of the turnabout of an area that had become a notorious skid row. Over the following decades, more people moved into the area even as it maintained a quiet, post-commercial downtown vibe.

But now, with development booming, Sharpe says she is worried that traffic in the area already is too congested, especially with large commercial vehicles, and that some of the proposed hotels are going to be lightly supervised operations that will offer short-term accommodation for rowdy groups.

"We want to see residents, a real neighborhood," she said. "We don’t want to see hotels and Airbnb and all that. We've got plenty of those, and they're already a nuisance."

In a letter to residents, Hardie outlined plans to have the hotel lobby entrance on St. Charles Avenue with a retail/restaurant entrance located on the Julia Street side, directly across the street from the $50 million, Julia Street Apartments development that is nearly completed. That development has 197 apartments and 17,000 square feet of ground-floor retail space, including the Oprah Winfrey-affiliated True Food Kitchen restaurant.

Jack Stewart, president emeritus of the Lafayette Square Association, has the same worries as Sharpe. The Hardie hotel proposal "really sounds like it'll be just a collection of party rooms," he said. "It's going to go over like a lead balloon."

Divided opinions

The neighborhood activists are especially opposed to the potential revival of a six-story Marriott Moxy hotel at 744 St. Charles Ave., almost directly across the street from Hardie's proposed development.

The owners of that site, Barry and Lorraine Dinvaut, were given the green light from the city in 2016 despite protests from local residents. But the project was stalled when financing arranged by First NBC Bank disappeared with the bank's collapse in early 2017. The Dinvauts have been talking to city officials about reviving that project, though Lorraine Dinvaut said they haven't decided whether to proceed.

Plans for a five-story Moxy Hotel in the Central Business District gained final backing Thursday from the City Council, paving the way for con…

The neighborhood activists also worry about 710 Baronne, which had been the old A.D. Wynne Furniture showroom, next to the Hancock Whitney Bank and across Baronne from the CBD Rouses supermarket.

That was originally envisioned as The Marquis, promising 19 luxury condominiums with private balconies and a rooftop swimming pool.

The downtown New Orleans property at 710 Baronne St., shown here in 2019 prior to redevelopment.

The developer Gerard Breaux, who with Terrell-Fabacher Architects won a Louisiana Landmarks Society historic preservation award in 2017 for converting the old American Sugar Refining Co. warehouse near Woldenberg Park into condos and offices, recently proposed changing the Baronne Street project into a hotel. Last week, that got a thumbs down from the Architectural Review Committee of the CBD Historic District Landmarks Commission. Breaux is appealing that decision with the City Council.

Still, not everyone in the neighborhood is opposed to new hotels or tourist traffic.

Mary-Jo Webster, chief executive of Aunt Sally's Pralines, which owns a factory and shop next door to the proposed Marriott Moxy site, said she'd be delighted to have two hotels in close proximity to her outlet.

"Any development that brings tourist activity into the neighborhood is a good thing for Aunt Sally’s," Webster said. "Half of what we sell is to tourists, so that would be just swell."

In addition to its ambitious $370 million capital campaign, the National World War II Museum plans to build a 234-room hotel and conference ce…

City Councilman Jay H. Banks, whose District B covers the historic area, has been treading carefully when it comes to these matters, according to his staff.

"We’re very mindful of the neighborhood concerns, and the councilman researches, considers and is watchful about all the applications that come through," said Jenna Burke, Banks' director of land use.

Banks is aware of the concerns of residents who feel they're getting overwhelmed with tourist businesses, and he wants to make sure that "everybody gets a seat at the table, even if nobody goes away 100% happy," Burke said.

Lunn, the City Planning Commission member, agrees that each case in the Lafayette Square zoning district should be considered on its own merits.

"As dynamic as it is downtown right now, I understand why there are different opinions about what should be done in that district," she said.

"I think this whole city faces that, and we have to ask each time: What are we preserving here, what are we creating, and what is essential to New Orleans?" said Lunn. "We're always trying to balance the welfare of the city as a whole and the rights of the residents who live near these establishments."