The Hubbard County Coalition of Lake Associations (COLA) coordinated its own loon-monitoring program this summer.

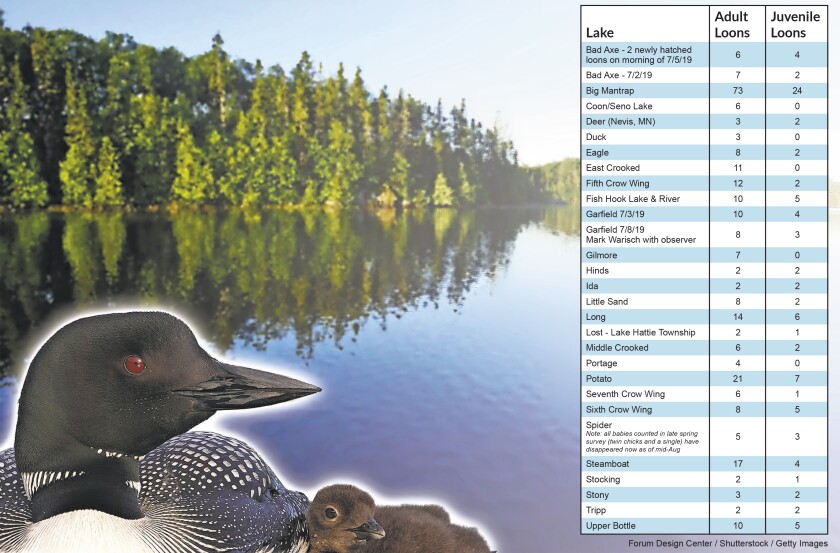

Twenty-seven lakes participated, volunteers venturing out to count the number of adult and juvenile loons present on their lakes during a 10-day period.

They also observed weather and water conditions, the percentage of disturbed/developed lake shoreline and other bird species.

All of the volunteers followed the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) protocol for the study, then submitted their results to COLA.

ADVERTISEMENT

The DNR program

The DNR’s Minnesota Loon Monitoring Program is a long-term project collecting information about common loon numbers on 600 pre-determined lakes, explained Christine Herwig, a Minnesota DNR nongame specialist for the northwest region.

In late May, as part of this effort, the DNR launched a new online system to help volunteers identify lakes available for monitoring. They also recruited more volunteers to help count loons on 150 specific lakes in Aitkin, Becker, Crow Wing, Cook, Itasca, Kandiyohi, Lake and Otter Tail counties.

COLA president Sharon Natzel said a number of loon lovers were disappointed that Hubbard County loons were not included in the DNR’s monitoring program. With assistance from Herwig, COLA launched its own study.

“We’ll continue it as long as there is not a DNR one in Hubbard County,” Natzel said. “We care about our loons, and we might as well count them. People have a good time doing it.”

Volunteers will be needed again next summer. To sign up, email hcCOLAmn@gmail.com. Provide your contact information and the lake you plan to monitor. COLA provides materials and training.

Eyes on the water

Bill Karsten, president of Garfield Lake Association, and Mark Warisch, a lake association member, were among those who volunteered this summer.

ADVERTISEMENT

They counted 10 adults and four chicks during their first survey.

“From egg stage to adult is a 14-week process,” Warisch said. “They’ll lay generally one to two eggs. They’re brown in color. It’s 24 to 30 days for incubation. Both male and female sit on the nest.”

Warisch has been a Minnesota Loon Watcher for 15 years. In March 2019, the DNR put that program on hold.

Since 1979, Loon Watchers have provided detailed information on nesting success, number of loons, breeding pairs, interesting occurrences and problems that may negatively affect the loons. Over the course of 39 years, the Loon Watcher program had grown to more than 300 volunteers on nearly 400 lakes.

According to a letter from Michael Duval, DNR district manager for the division of ecological and water resources, “We will spend the next several months re‐evaluating the program objectives and considering our options for relaunching the survey, including development of a revised database platform, all with the hope of being able to restart the volunteer survey program in the near future.”

When Warisch learned that COLA was looking for loon-monitoring volunteers, he quickly signed up.

ADVERTISEMENT

Monitors were asked to count loons on their lakes between June 28 and July 8 and report their findings. Surveys could be done by boat, pontoon, canoe, kayak or from shore. The collected data will be shared with the DNR.

In addition to loons and their chicks, observers reported other “bonus” wild bird species that were nest building, nesting or bearing young. Examples are bald eagles, ospreys, trumpeter swans, great blue heron and American white pelican.

“Loons are really popular on this lake,” Warisch said.

Case in point: Caleb Dubbe, as a third grader at Laporte School, drew a color picture of a loon and chick that raised $150 at an auction. The money was used by the Garfield Lake Association to increase watercraft inspection at the public access. They also incorporated his drawing into their logo.

Of the 104 parcels on Garfield Lake, Warisch noted, 55 property owners belong to the lake association. The nonprofit organization formed after zebra mussel larvae, called veligers, were confirmed in a water sample taken from the lake in September 2017.

“We have really good participation on this lake. People are really concerned about the loons and water quality,” Warisch said.

Garfield has three bays suitable for nesting, so it can sustain six loons, he said. Big Mantrap Lake, on the other hand, hosted 73 adults and 24 chicks, thanks to its many coves and points, plus its loon nesting platform program.

Why monitoring is important

Herwig said long-term monitoring is important to understand trends associated with loons, which are a long-lived species. Loons can live up to 20 years, but on average nationally, they only hatch one chick every other year.

ADVERTISEMENT

The annual loon count gives the DNR the ability to detect changes in the adult loon population and to anticipate any problems that could jeopardize the future of loons in Minnesota.

“Often more than 10 years are needed to look at trends because of annual variability in weather, lake productivity, as well as many other factors. Even with 10 or more years of data, trends can be challenging to detect,” she said.

Beloved for their haunting call and beauty, loons are also “good indicators of water quality because they need clean, clear water to catch food.”

“They are visual predators, sensitive to disturbance and lakeshore development, indicators of the effect of contaminants – like mercury and lead in the environment – and enjoyable for Minnesotans to watch,” Herwig said.

She said lake residents provide valuable data and perspective through their involvement. She appreciates that COLA members expressed interest and commitment to loon monitoring.

“Almost everybody loves loons. It’s almost universal,” Herwig said.

ADVERTISEMENT

To see which lakes outside of Hubbard County need a loon monitor, go to mndnr.gov/eco/nongame/projects/mlmp_state.html and click on “Volunteer Map.”

West Nile virus’ effect on loon

In July, the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine’s (CVM) Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory received three deceased loons from northeastern Minnesota.

After testing two of the loons, Dr. Arno Wuenschmann, a professor of pathology at the CVM, diagnosed West Nile virus (WNV) as the cause of death.

Public officials are trying to decide what to make of this finding in Minnesota’s iconic state bird.

Wuenschmann has more than 15 years of experience tracking the disease across the state. “It’s not well-known that loons can acquire and die from West Nile,” he said.

Fourteen years ago, Wuenschmann tested an entire family of loons that passed away from WNV. “So I would say loons are highly susceptible to West Nile virus,” he said, adding most people don’t realize this because loons often die in the water, making them hard to access for sampling.

WNV was first confirmed in Minnesota in 2002, and was documented as a cause of loon mortality in Minnesota as early as 2005.

It is not uncommon for people, animals and birds to be exposed to WNV through mosquito bites. Most people and animals successfully fight off the virus and develop antibodies against future infection. Some birds, like loons, crows and other corvids, are especially susceptible to the infection.

ADVERTISEMENT

Loons can die from a variety of illnesses and injuries and individual bird deaths are a normal occurrence and not cause for alarm, according to a DNR news release.

“Minnesotans love our loons and it’s concerning for people to find them dead. When we start seeing multiple birds dying on a single lake, we want to know about it so we can start tracking the information and determine when further testing is warranted,” said nongame wildlife specialist Gaea Crozier. “While there isn’t a way to treat the West Nile virus infection, knowing the cause can help us rule out other, preventable causes of mortality.”

Hubbard County lake homeowners and other lake users who observe two or more dead loons on a single lake with no obvious injury or cause of death are asked to email Herwig at christine.herwig@state.mn.us.

Individual bird carcasses can be disposed of by burial or in the trash. There is no evidence people can contract WNV from infected birds, but gloves or a plastic bag are recommended when handling any dead animal. If reporting numbers reach a threshold that indicates a need for further testing, more information and handling protocols will follow.