'Tis the season to celebrate the Apollo program’s first human excursion to the lunar surface in July 1969. Fifty years later, this epic and ground-breaking achievement certainly warrants praise as it set the technological stage for generations of engineers and scientists to follow.

But there is also the temptation to say that America needs another Apollo-style program to reclaim its primacy in space. This sentiment ignores both the realities of the moonshot and the amazing possibilities that the current commercial space revolution is opening.

Here’s a few reasons why what’s happening now is even better than Apollo.

Protected From Politics

Apollo was born of Cold War desperation: a political exercise that paid enormous scientific and technological dividends. After the launch of Sputnik in 1957, it became vital to beat the Soviet Union to the Moon, a geopolitical urge that created an enormous budgetary effort.

The problem with politically motivated—well, anything—is that the faucet of support can be closed just as quickly as it opened. It happened to Apollo, as follow on missions were cancelled and the focus shifted to a reusable craft to service low-earth orbit. This pattern of shifting space priorities and strategies whipsawed NASA, most noticeably when the Obama administration’s cancellation of the Bush-era Constellation moon program in 2010.

But multiple private companies pursuing their niches in space have an obvious redundancy. While companies may rise and fall, the very nature of a commercial effort isn't as dependent on government funding. If it’s worth doing, especially if it makes money, space industry will endure political shifts. The objectives of a well-run company do not change that much every four years.

That leaves today’s NASA with a choice: Do it themselves and control everything (the traditional way), or fund private companies to develop the tech the agency needs and then allow them to sell their services to any nation, company, or individual (the new way). With those services on the open market, NASA would be one of many customers for a new U.S.-based space economy.

This debate is boiling over right now. The ongoing effort to return to the moon, called Artemis (after Apollo’s sister), is becoming a lesson in the advantages of the commercial model.

So Much Cheaper, Even NASA Noticed

One measure of Apollo’s urgency is the amount of money the government spent on it. The moonshot consumed 2.5 percent of America’s gross domestic product over a 10-year period, for a total of $25 billion, or about $150 billion in today's dollars. If we apply the same urgency to today’s GDP, a similar-sized percentage would be more than $100 billion every year.

For some perspective, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine last week said the agency will need $20 billion to $30 billion over the next five years. This is sizeable as NASA’s budget is likely to hover around $20 billion annually, so they’re looking at $5 billion or so more each year. The pushback generated by this request—it’s too much, it’s not enough—crosses the political spectrum, following Congressional district lines more than party affiliation.

If only investment guaranteed results. For those who miss bloated, government-run spaceflight, there is already a NASA spacecraft mired in the old ways of thinking. The feds have sunk a lot of money into the Space Launch System, a mega-rocket built to NASA specs for deep space missions. It was supposed to fly in 2017, but we’ll be lucky to see a first flight in 2020—and it busted the $9.7 billion estimated budget, now costing about $12 billion.

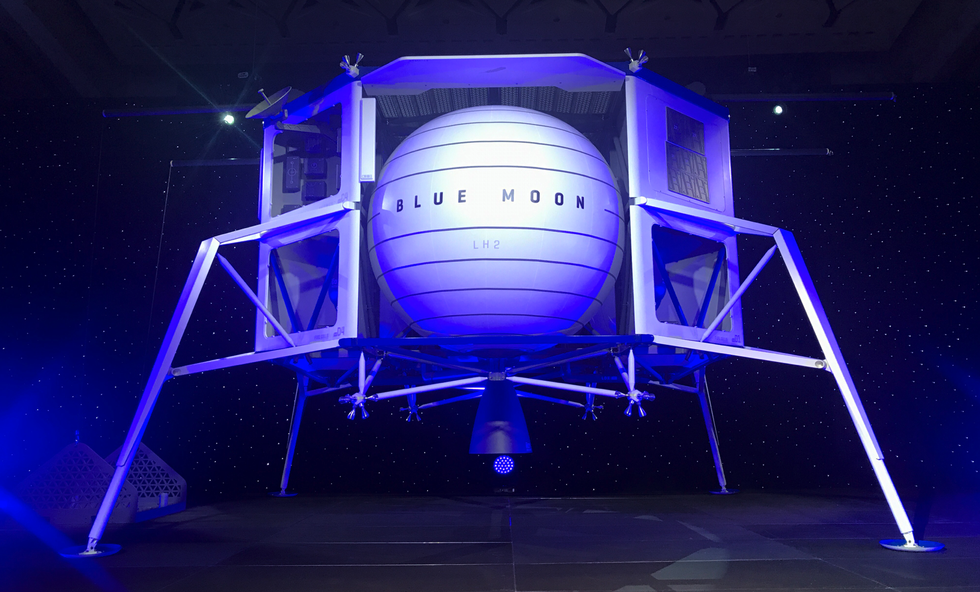

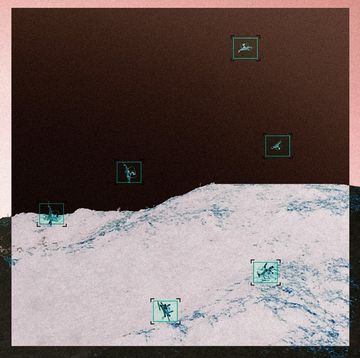

But something happened during these SLS delays: the commercial space industry started delivering on its promises. Most visibly, private firms have been delivering supplies to the International Space Station for years and (hopefully soon) will ferry astronauts as well. Blue Origin and SpaceX has started development of crewed spacecraft able to reach to the moon and Mars. Elon Musk even sold a moon trip to a Japanese billionaire.

The speed and relatively cheap cost of these operations has impressed Bridenstine, who sees the commercial space industry as a key enabler to accelerate the timeline. "We're going back to the Moon, but we're doing it entirely different than we did in the 1960s," Bridenstine told reporters recently. “The reason we need commercial operators is because they can drive innovation if they're competing on cost.”

There are plenty of things that the private sector can provide for NASA’s moonshot, using the new model. A space station near the moon, robotic landers, and new spacesuits are all going to commercial firms, who will ultimately own the blueprints and offer proven equipment to whoever wants to pay to use them.

Bridenstine has even publicly pondered the idea of using commercial space heavy rockets to reach the moon. If that happens, it will be a true death knell for the traditional, Apollo approach.

A Truly Global Impact

Planting the American flag on the moon is a big moment in human history, but it's often framed in terms of a U.S. victory over its geopolitical rivals. The moon landing was a demonstration of national power, pursued in a jingoistic fervor, as most government-funded feats of explorations tend to be.

The commercial space industry is more inclusive. In fact, it has to be in order to survive. The current commercial satellite launch market survives on a similarly global customer base. Simply put, telecom companies from around the world will pay Chinese, European, or American launchers to put their spacecraft into orbit.

Now extend that thinking to even more industries. There are plenty of potential customers who would pay to ride on a commercial space vehicle and orbital facility: Medical tech companies lofting research experiments, universities paying for small space telescopes, Middle Eastern and African countries sending their first astronauts to space.

With NASA giving developers the ability to market their rockets, spacecraft, and orbiting stations, the entire world will enjoy the benefits of this new space age. There are many who see spaceflight as the way to bring the world together, and the commercial space industry could make that happen.

It won’t be cheap, and there will undoubtedly be conflict when marketing plans clash with national priorities. But when it comes to people using and, eventually, living in space, there is no bigger chance in human history for the whole world to participate.

So this summer be sure to celebrate Apollo and all those who made it happen, but also keep an eye on what’s going on now because it has the chance to become something even bigger.

Joe Pappalardo is a contributing writer at Popular Mechanics and author of the new book, Spaceport Earth: The Reinvention of Spaceflight.