US, Nevada rates of kids without health insurance increase

The number of children without health insurance rose in every state last year, raising a red flag for advocates who worry fewer children will receive preventative and emergency care, according to new report from Georgetown University.

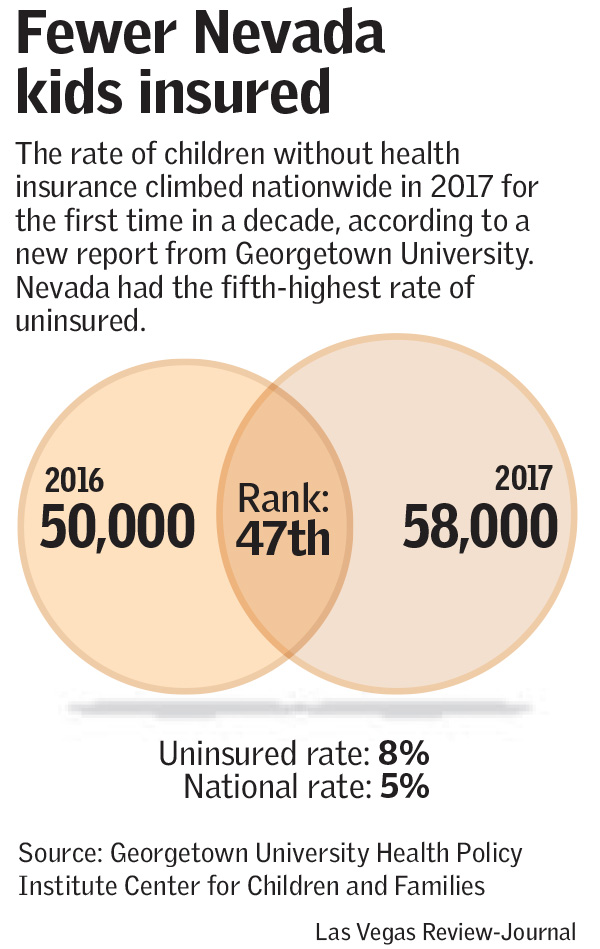

After falling to an all-time low in 2016, when 4.7 percent of children nationwide were uninsured, the rate ticked back up for the first time in a decade in 2017, to 5 percent, according to the annual report released Thursday by the Georgetown’s Health Policy Institute Center for Children and Families. That reversed a downward trend that had seen the rate of uninsured decline five percentage points since 2008, when the center released its first report.

Nevada’s rate rose 1 percentage point to 8 percent — meaning 8,000 fewer kids in the state had insurance last year, according to the report.

Like ‘night and day’

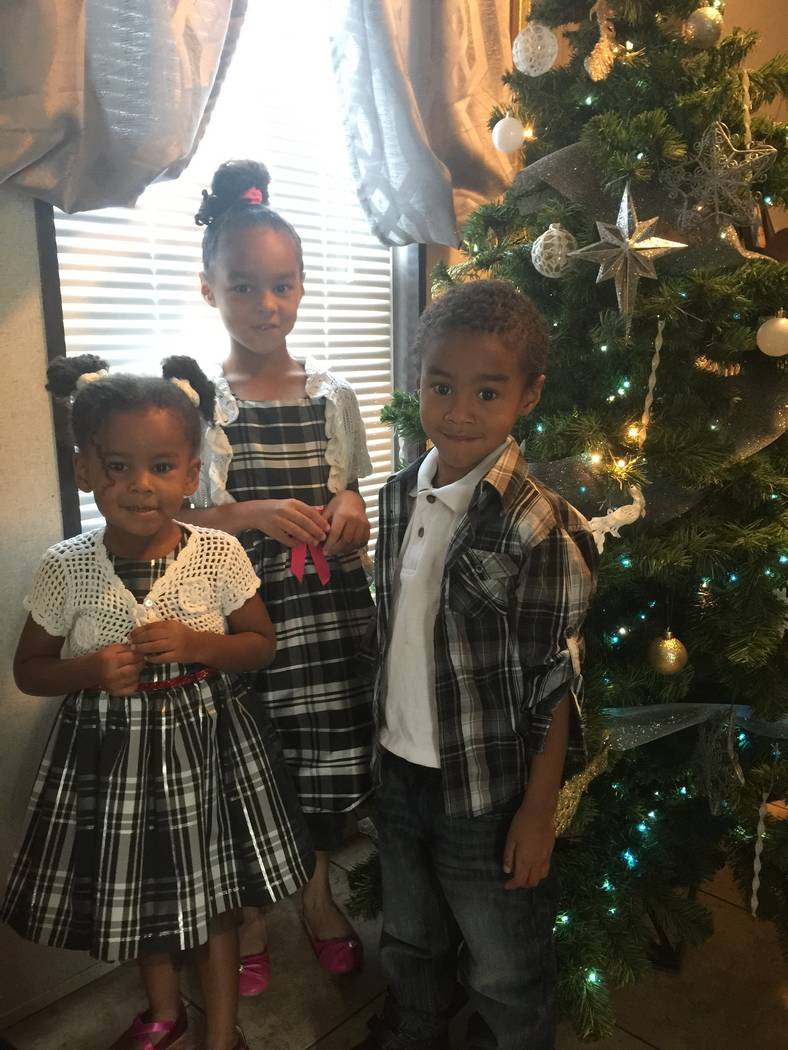

Among them was Emily Allen’s 3-year-old daughter, Andrea Harris, who had been insured under the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) but was dropped.

“I have to get her 4-year-old shots in a week or so, and I’m stressed about if I’m even going to be able to take her there,” Allen, of Las Vegas, said Thursday. “It’s not a cost we were expecting to incur.”

Her older children, Adesina Neal, 6, and William Neal, 5, are insured under Medicaid. Because they can go to the doctor whenever they need to, Allen doesn’t stress about their well-being.

“It’s literally night and day, just knowing that I can take my other two for anything,” she said. “I have total peace of mind.”

Joan Alker, the Georgetown center’s executive director and a coauthor of the report, said talk of repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act and a monthslong lapse of funding for CHIP likely contributed to the decline in enrollment.

The number of children covered under parents’ employer-sponsored insurance plans increased less than 1 percent in 2017, but that was offset by a decrease in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment and in plans purchased on and off state exchanges.

“I was certainly worried that this would be the first year the number went in the wrong direction, but what I was surprised by was that there was no state … that was able to make progress,” Alker said. The District of Columbia was the only locale to see a decrease in its rate of uninsured.

The decline runs contrary to what experts would expect during times of economic stability. Usually, fewer are uninsured when unemployment is low, Alker said.

‘Our star performer’

Nevada’s rate of uninsured was among the highest in the nation, behind only Texas, Alaska, Wyoming and Oklahoma. Though the increase wasn’t statistically significant, the change in the number of uninsured was, rising from 50,000 in 2016 to 58,000 in 2017.

Many Nevada children gained coverage in 2014, when Gov. Brian Sandoval expanded Medicaid to include residents with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

“A couple years ago, Nevada was actually our star performer of reducing the uninsured rate as a consequence of the Medicaid expansion,” Alker said, noting that one-fifth of Nevada’s children lacked insurance coverage in 2008.

Emma Rodriguez, policy manager with the Children’s Advocacy Alliance of Nevada, said threats by the Trump administration and members of Congress last year to repeal the ACA, often referred to as Obamacare, confused parents and may have contributed to decreased enrollment in programs like Medicaid, CHIP and the state-based health insurance exchange.

Alker and Rodriguez both expressed concern that without broad political support for existing programs for families, especially low-income households, the trend could continue.

“This is a big red flag that we’re moving in the wrong direction,” Rodriguez said.

In an impassioned blog post, Alker warned that without insurance coverage, children lose access to check-ups, immunizations and prescriptions, and more often miss school, leading to worse economic and educational outcomes in the long run.

“These findings are a stark warning that our nation’s progress in covering children is at risk,” she wrote.

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter.