Las Vegas’ homeless camping ban faces legal, logistical hurdles

At the corner of First Street and Garces Avenue in Las Vegas, a barefoot woman whispers to herself. A man, using his stuffed suitcase as a pillow, sleeps on the sidewalk, wrapped in a brown sheet like a mummy. Nearby, against a cement wall, Harry Reynolds and his fiancee, Alice Pate, spread out three blankets and set up camp for the night.

“God wants us to be together,” Pate says. “At the shelters, they want to separate us.”

Such personal calculations for the homeless may soon get more complicated if the city adopts a proposed ordinance making camping and sleeping in public areas downtown and residential areas throughout the city a misdemeanor crime when beds are available at established homeless shelters. The proposal was introduced this month by city officials desperate to stem the tide of homeless people in the urban core and compel them to seek help.

Beyond questions of its legality, the ordinance is already facing intense scrutiny from critics who argue it will only criminalize the destitute and vulnerable. Officials counter it would be one more layer in a broader strategy to protect the homeless and general public, safeguard business interests and address an escalating public health crisis.

Ahead of expected lengthy deliberations on the proposal set to begin Nov. 6, there is a consensus among City Council members that the conversation is needed to address what is widely seen as a worsening regional problem.

What will come of the new effort is unclear; at least three members of the seven-member council say they have not decided whether they will support the camping ban.

“I look at this as an effort of desperation, really, to try to figure out how to manage a situation that is almost unmanageable,” said Councilman Brian Knudsen, who sought talks involving longer-term solutions. “The city’s (already) taking really proactive steps, but it’s not enough, and it’s not fast enough.”

Like Knudsen, Councilman Stavros Anthony and Councilwoman Olivia Diaz, whose Ward 3 district is in the heart of downtown Las Vegas, said they are still on the fence.

Councilman Cedric Crear, who also represents downtown areas, did not make himself available for an interview.

The three other council members, including Mayor Carolyn Goodman, have expressed support for the measure.

“This ordinance is not to put folks in jail,” said Councilwoman Victoria Seaman, who backs the law. She noted that the city’s Courtyard Homeless Resource Center on Foremaster Lane offers much-needed assistance. “It’s to help them get them where they need to go and not have the encroachment upon businesses where you have folks sleeping in doorways.”

These officials say downtown businesses have been a driving force behind the proposal.

Among those pushing for action is attorney Gerald Gillock, whose office sits at the corner of Clark Avenue and Fourth Street. He said he arrives daily to the sight of hypodermic needles and trash and the stench of urine and feces.

“They’re going to the bathroom everywhere. I had that happen 10 times in two weeks,” he said. “I even thought ‘I’ll get their attention’ and scooped it up in a shovel and walked it over to City Hall.”

But Gillock doesn’t think the ordinance is the solution. He called it “useless” because the shelters are already at capacity, and the ordinance wouldn’t require the city to provide public sanitation facilities.

Legal battles possible

The city’s plan may face legal hurdles, though City Attorney Brad Jerbic said he believes it would hold up in court.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned a similar camping ban in Boise, Idaho, last year because, without guaranteeing enough shelter beds were available, it was deemed cruel and unusual punishment. That case could end up before the Supreme Court, but Las Vegas intentionally drafted its bill to include “if beds are available” language to avoid that particular controversy.

Jerbic said he plans to present to the council information on complete or partial camping bans in place in 10 other jurisdictions. He suggested that the 9th Circuit, which oversees Nevada, is an outlier on the subject.

But Eric Tars, legal director of the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty, who worked on the Boise case on behalf of six homeless individuals, said the 9th Circuit is not going its own way. The fairly conservative 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which handles cases in the Carolinas, Virginia, West Virginia and part of Maryland, and the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Florida have issued similar rulings, he said.

Tars also argued that the ordinance could be counterproductive, saddling the homeless with arrest records and tickets they can’t pay, keeping them from getting jobs and housing — Nevada has the fewest available affordable units in the country — and possibly leading to the loss of lifeline government benefits.

Rather than “try to thread this constitutional loophole,” Tars said, Las Vegas could learn from creative solutions used in other cities, such as temporarily using vacant spaces as shelters, rotating shelters among different churches and offering pilot programs that allow residents to host tiny homes in backyards or provide safe parking options for people living in vehicles.

“You can’t just exile people you don’t want to see in your downtowns,” he said.

For some, living on the streets in the so-called Corridor of Hope on the edges of Las Vegas Boulevard North has become a monotonous routine. By 6 p.m. Wednesday, for example, hundreds of men lined up for a bed at Catholic Charities of Southern Nevada. All 500 beds there were filled that night.

Others waited for dinner and a bed at the Las Vegas Rescue Mission, where 191 stayed overnight. The shelter was over-capacity, forcing some to crash on cots and couches.

At the Salvation Army the evening before, the 104 walk-in beds for men and women had filled by 7 p.m.

All told, there are only about 2,000 beds for more than 5,500 homeless people on the streets in Southern Nevada on any given night, according to this year’s homeless census. Clark County estimates that more than 14,000 are homeless at some point during the year.

Jerbic said a plan to address the bed shortage will be unveiled when the camping ban is discussed at the Nov. 6 meeting. He declined to provide details.

“We do have plans to always have a certain number of beds available just for this reason,” he said. “They won’t be available on a daily basis except when needed for this ordinance.”

The city has said it will not turn anyone away at the open-air, 24/7 courtyard. But more than 300 stay there on any given night, even though there are only 220 mats for clients to sleep on.

Mental health services

Even if there were beds available, Deacon Tom Roberts, CEO of Catholic Charities, said he worries that if those who choose to sleep on the streets were forced to seek shelter, they would run from resources and officers on the Metropolitan Police Department’s outreach team.

More resources should be put toward mental health and addiction treatment, he said.

“You can arrest people all day long, and, frankly, you can put them in an apartment, but if you can’t treat the reason why they’re there, the apartment will become an insane asylum,” Roberts said. “Even if we had an open bed, I can’t put someone upstairs in our dorm environment who doesn’t want to be there. That creates a safety risk.”

Dealing with homeless people who are mentally ill or addicted to drugs is not covered by the proposed ordinance. That is another dividing line in the debate.

Diaz, one of the undecided City Council members, has suggested using specialty courts to divert homeless individuals in need of addiction and mental health treatment or housing.

But in an interview with KNPR this month, Goodman resurrected an idea her husband, Oscar, championed when he was mayor — turning a former state prison near Jean, 30 miles south of Las Vegas, into a facility for people with severe mental illnesses, which she said is one of the biggest problems among the homeless population.

While such big-picture concerns occupy policymakers, others are working to figure out how a camping ban would work on the street level.

Lt. Tim Hatchett, who supervises Metro’s homeless outreach team and has a background in social work, said that while specifics about how the ordinance would be enforced haven’t been spelled out, he doesn’t foresee such a law putting an undue burden on his team or patrol officers who regularly interact with the homeless.

“We always have the capability of determining what we’re going to enforce, right? … If we pull you over for speeding, you’re not always going to get a speeding ticket. You might get a warning. You might get a reprimand,” he said.

“But if you’ve done everything you possibly can for this person, you have to have something to say: ‘OK, it’s time for you to get some help, right?’ I think that’s what they’re looking for.”

Anthony, the councilman and a former Metro police captain, said that law enforcement, including city marshals, must commit to enforcing the new rule, and the city must have a system in place to alert officers about bed availability.

Hatchett said that wouldn’t be a big challenge, since his officers already communicate with shelters on a daily basis.

Jerbic, the city attorney, also said the city and Metro have personnel designated to communicate with each other during each shift.

Support network

Less clear is how the homeless would adapt to new routines.

Anthony Lowe, who has stayed at the Salvation Army shelter since economic issues put him and his wife on the streets in March, said he often must decide between a bed or food on days when ministries do not bring meals to him. The arthritis in the ball joints of his feet makes it difficult for the 64-year-old to make the uphill trip to a feeding shelter more than a mile away.

“But normally I don’t because I have to be in line (for a bed),” he said. “If you’re able to walk, you can pretty much eat all day.”

Kathleen Sutton, a 58-year-old former investigator for a pharmaceutical company who has fallen on hard times, said she believed passage of the ordinance could add another element of instability to an already precarious existence.

Bankruptcy sent Sutton to the streets in June. Her fear of being alone as a disabled woman on a motorized scooter galvanized her to quickly find a support network, which includes Pate, Reynolds and an 86-year-old homeless Korean War veteran they all call “dad.”

They offer her protection. Sutton said she has been sexually assaulted, watched a man get run over in a nearby desert lot and tried several avenues to get help. She said she is on the waiting list for affordable housing. She is number 841.

“I’m a tough girl, but I’m scared being by myself,” she said. “Where do the homeless go? The marshals come in. They ask you to get off the street. Where do you go? Down the street, until we get woken up again? So where do we go?”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter. Contact Shea Johnson at sjohnson@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272. Follow @Shea_LVRJ on Twitter.

The city's commitment

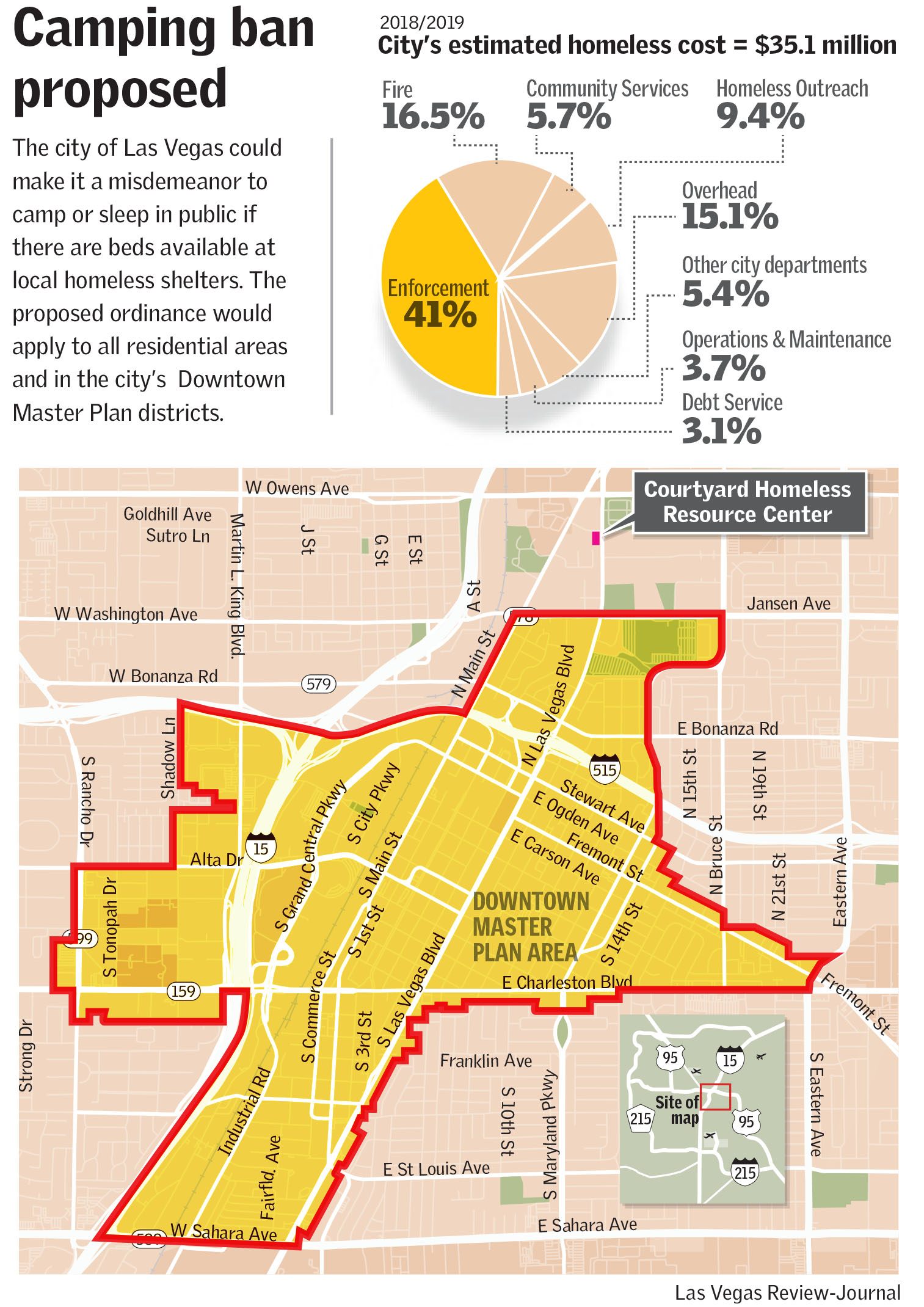

The proposed ordinance is just a piece of the city's homeless initiatives. This year, the council also approved master leases for affordable housing, and in the last fiscal year spent $35.1 million on homeless issues.

But the cost is only going to escalate: The City Council last month received a report that said Southern Nevada spends an average of about $26,500 for each homeless person that it interacts with, a total that is expected to climb to about $369 million this year.