It’s a warm summer evening and Devan Clapp is standing outside his two-story brick row house in northeast Baltimore’s Ramblewood neighborhood. The streets are quiet, with postage-stamp lawns; a transition area between the city and the suburbs of Baltimore County just a couple miles north.

This neighborhood, like every other Baltimore neighborhood Clapp’s family has lived in the last hundred years, was predominantly white, before it wasn’t. He talks of how, in the 1980s, the skin color of his mother and father, godmother and brother, drove their white neighbors up and over to the “more-welcoming” side of the county line.

“When I was younger, the neighborhood was divided, pretty much 50 percent white and 50 percent black. As a youngster I didn’t know it was happening, but now I look back and they’re all gone,” says the 39-year-old Social Security teleservice rep.

There are a few other areas in Baltimore with the same low crime rate and housing stability as Clapp’s neighborhood. However, most of those areas have seen heavy development and investment—bike lanes, tidy parks, and running paths. Clapp’s neighborhood looks as it did 30, maybe even 50, years ago.

“I’m standing outside right now and looking at the alley, the streets, and the pavement. It just doesn’t scream I want to go for a run,” says Clapp. It’s not that he’s against running those streets—he often logs a few evening miles in the neighborhood. But in his part of the city, running paths are nonexistent and the closest runnable park is three miles away.

Even so, within Baltimore, Clapp’s neighborhood is better than most—neighborhoods where sedentary lives are bred from childhood; places left in the margins of Baltimore while resources pour into the already-affluent blocks. Those historically overlooked areas are large swaths of the city that are predominantly black and have been torn apart by decades of failed political leadership, corruption, and unabashed segregation.

To run in them is to run past corner boys calling out the street names for drugs, and scabbed-over addicts. Running past side alleys, you see rats the size of Nerf footballs dart out from piles of busted household appliances, soiled clothing, and all manner of how-the-hell-did-that-get-here trash. These are areas where you don’t run up behind someone without calling yourself out—“Good morning! Runner behind you!”—or moving into the street; if not for your own safety, then as a courtesy to pedestrians on edge about theirs.

To run in those areas is also to run out of them within just a couple blocks, through an invisible wall that turns into white Baltimore—a place that is surely separate, and distinctly not equal in job opportunities, infrastructure, and education.

Running in Baltimore traces the blueprints of divisions that have stood for a century. While other cities close their chapters on segregation, Baltimore languishes. Here, running breaks no boundaries.

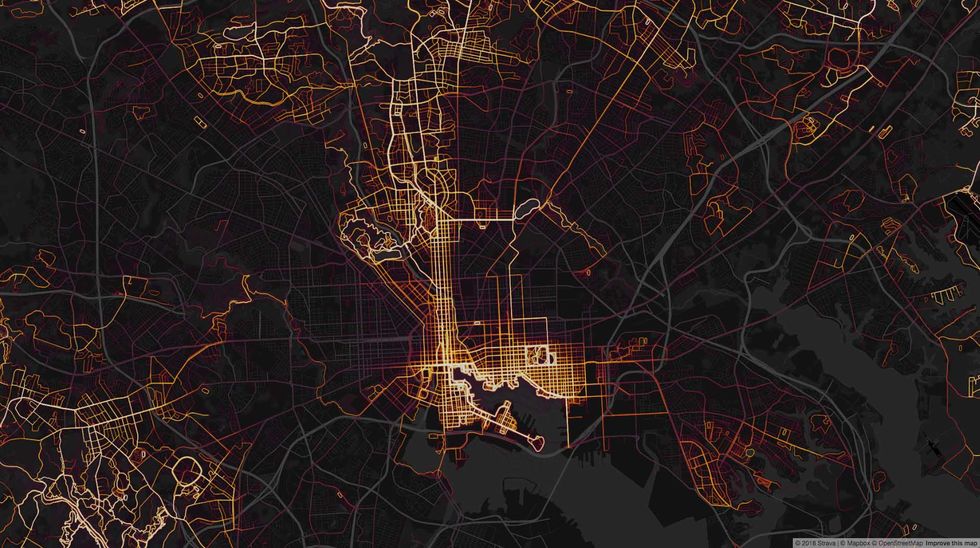

Several miles south of Clapp’s house lie the hottest Strava routes in Baltimore. Almost every one follows the wide, brick promenade that curls around the waterfront of the Inner Harbor, the city’s crown jewel. The path winds past the tourist shops and high-end Harbor East, through the historic, cobblestoned Fells Point and down to the Canton Waterfront Park.

The promenade is where Baltimore’s running groups meet, from the bunches of loosely organized friends, to the tattooed and mean-mugging Faster Bastards club, and the colorful and caffeinated November Project.

It’s also where Clapp’s running group meets on Sunday mornings. A handful of mostly-black runners known as the RIOT (Running Is Our Therapy) Squad Running, the group started as a response to the “trauma and suffering happening in Baltimore in people’s personal lives,” says founder Rob Jackson, 37, a contract specialist for the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers. For them, running “can be used as a stress reliever and as a way to get healthy, in a city where the life expectancy difference is significant [six years] between blacks and whites.”

They start at 8 a.m., before the tourists begin milling about, with a few miles around the water at an “all are welcome” pace. Most of the runners live more than 20 minutes away, and most travel by car to get there. Clapp himself takes a 30-minute bus ride from Ramblewood, but says it’s worth it, if only for the view.

“There’s that desire to see something scenic when you’re running, something less mundane,” he says. “You want to see something that makes you feel different.”

It’s the city's top place for runners for good reason. In a city beset by an endless cycle of growth and decay, it exists as an idyllic escape. Uninterrupted, the path hugs seven miles of waterfront, past sailboats nodding in their slips, lively patio bars, and even a stretch of sandy beach used as a trendy social pop-up. You’ll even see police on foot patrol and sanitation workers picking up trash—unicorns in most of the city.

The promenade route lies as a larger puzzle piece in the city’s running scene, one that we all run, but that few want to acknowledge.

When viewing the Strava heatmap of Baltimore, the most-run routes of the city meld to form the outline of a letter “L” that glows like neon. It begins in the north and runs straight down the city’s spine, before diverting east along the Inner Harbor and the promenade. This area of Baltimore is also a demographic phenomenon known as “the white L.” It’s the area where resources are directed, where prospective homebuyers are guided and luxury apartment complexes are erected. Its lines are as obvious in real life as they are on the Strava heatmap, and most people who live inside of it stay inside of it.

Just as obvious are two areas outside of it, segregated to the left and the right. They’re Strava deserts where running seems nonexistent, or if there are runners, they don’t use GPS. These stretch around the Patapsco River and out to the county lines, forming a rough shape of wings. These areas are pocked with vacant rowhomes, soaring poverty levels, and generational despair. Another phenomenon, “the black butterfly.”

As a youth, Clapp attended Baltimore City College, a public high school with an active sports program. “A lot of my friends got their running in by way of football or basketball practice,” says Clapp. But he wasn’t very athletic.

Running wasn’t a part of his life until much later into adulthood, when he was able to reflect on the benefits of it. For many children in Baltimore, it’s the same. Physical education, much less running, isn’t a priority.

In Maryland, the requirement for physical education is low, just one day a week between kindergarten and eighth grade, and a 0.5 credit of the 21 required to graduate high school. A 2018 report funded by Baltimore-based Under Armour and the Aspen Institute found that most schools in their target zone of East Baltimore provided little more than the minimum requirement for physical education. “There are basic fitness issues,” said one educator in the study. “Kids don’t have the fitness to walk on to teams.”

Outside of school, maintaining a healthy lifestyle becomes even more difficult. Baltimore is experiencing a violent crime wave of unforeseen proportions, even by Baltimore standards. In 2017, it recorded 342 murders, giving it the dubious distinction of the nation’s highest per capita murder rate of any large city, over twice as high as Chicago’s. Less than two-thirds of students in the Under Armour study said there’s a safe place to play in their neighborhood.

Without areas to run in, or even to play in, exposure to the sport is minimal. It’s compounded by the fact that running really is a luxury. Runners like to say that it’s not like other sports, you don’t need a glove, a court, or a carbon-fiber bike. You just need shoes. But running is more than shoes and an open front door. It is money—to enter races, or to buy real running shoes, which can cost a day’s wages. It is work, after working two other jobs. Running is time, to exercise. It is selfish, to go alone and into your own head, when others need that body at home. Even if the time and money aren’t obstacles, when the safer running routes are more than a mile away and no running groups in the city meet in your neighborhood, it’s easy to not want to be a runner.

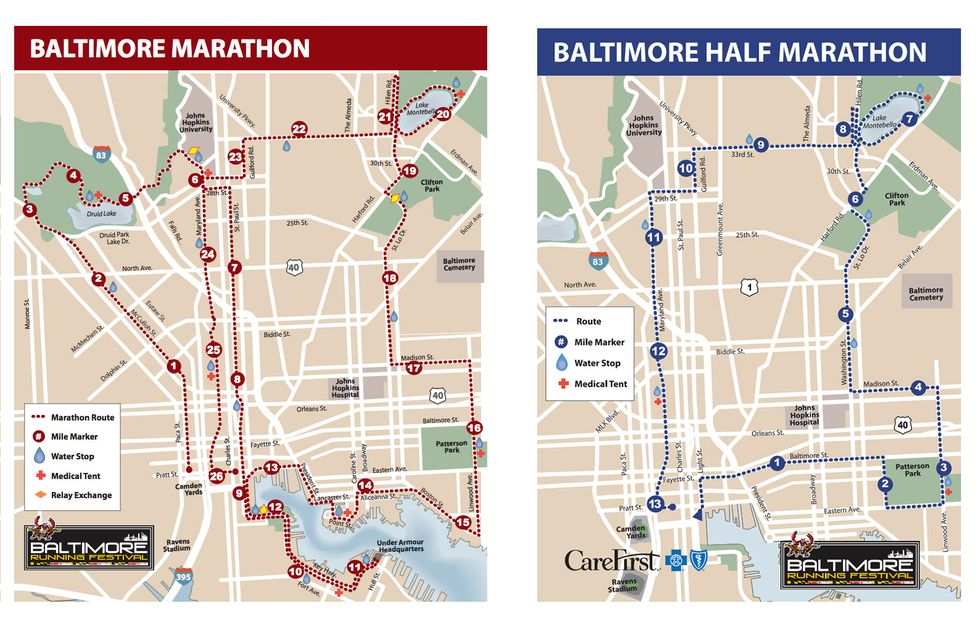

Every running store in Baltimore sits within the white L. Every major running group not only meets in the white L, but runs almost exclusively within its borders. The only races that go through a predominantly black neighborhood for more than a mile are the Baltimore Running Festival’s full and half marathon.

Clapp sees that lack of exposure as a major roadblock in the popularity of running in the black community. “People don’t see running happening so they may not think about starting to run,” he says.

One group leading the way for running in Baltimore’s black community is the Black Running Organization (BRO). Led in part by Isa Olufemi, a 37-year-old entrepreneur and organizer, BRO exists as a group that empowers black runners through embracing their heritage and developing unity. In addition to BRO, for three years, Olufemi also led a running club at Dunbar High School, in the heart of East Baltimore, known as the Poet Pride Run Club (PPRC). With grant funding for coaching and uniforms, the club of roughly 15 students met twice a week before school to run a few miles in the streets in Baltimore. In the 2017-2018 school year, the group ran over 1,500 collective miles.

Outside of running, they received educational support and assistance with post-graduation plans, including assistance with scholarship applications, and college tour scheduling. Every graduating senior in the program progressed to a higher education program, enlisted in the military, or entered the workforce.

When their run club took to the streets—almost entirely outside the white L—people perked up. Their joy was infectious and their running lit up the shadows cast by the high walls of the projects they ran through. People thank the runners for running. On one run this past May, a man flagged down the group and handed them all the cash he had in his pocket because of how impressed he was with their hustle and work ethic.

Others outside of the community began to pay attention too. The group was supported by Under Armour, which outfitted the students in new running gear, entry into the Baltimore Running Festival, and featured them in an ad campaign.

However, even with the exposure from Under Armour and the success of the program within Dunbar, the PPRC did not return to Dunbar for the 2018-2019 school year due to lack of funding. The original grant expired and private funding could not be procured to operate on a full-time basis out of Dunbar High School. Public funding for the program was never an option in a school system that just last winter suffered a heating crisis that affected a third of the schools and shut down the system, as classroom temperatures dipped into the 40s.

“You have to depend on a [government and public education] system that genuinely does not value you,” says Inte’a DeShields, 38, co-marshal of BRO and English professor at Morgan State University, a historically black college in northeast Baltimore. “I don’t think that this system is designed to really invest in everyone. And so the best teacher for us has been to say “Kujichagulia”—[the African principle of] self-determination—you gotta create that shit yourself.”

Olufemi is currently starting another youth running club in the city, one that doesn’t have to rely on outside funding and influence, so as not to be set up for failure. And even though the PPRC no longer operates within the walls of Dunbar High School, it continues to run in some capacity in conjunction with BRO. The students they’ve built relationships with over the last three years still come out to group runs; support and community continues through that. This all falls in line with the Black Running Organization’s foundational goal to restore and empower the black community through running.

“Black people are in a bad place right now, been in a bad place for a while. We come to resurrect the spirit of our people, and to do that, we have to be separate from other folks first,” explains Olufemi.

Lenny Johnson, 33, another member of BRO and a teacher in Baltimore, says, “I gravitate to people who look like me. I see value in those people even if the infrastructure is falling down, and I’m running past blocks with nothing but boarded houses. When I literally see people decaying on the streets, it’s like I’m running for someone else. Because people need to see that. They need to see someone who’s physically strong, also mentally strong.”

Clapp sees change coming as well. “Right now, running in the city is fragmented, but with more running groups popping up, they’re gonna get older and they’re gonna bring more people into it.” RIOT plans to start doing more runs throughout the city, with possibly a west to east run on North Avenue, through the heart of the unrest—486 arrests over 15 days—that came following the 2015 death of Freddie Gray, who sustained severe spinal cord injuries while in police custody for the possession of a knife.

On a larger scale, last year, Under Armour began providing uniforms for all student athletes in every Baltimore City public school, including track athletes. The move makes Baltimore the only city in the country to have all high school athletes supported both academically and athletically by a brand. In terms of physical spaces, they currently have one UA House in East Baltimore that serves over 100 students daily with academic enrichment, health, sports and physical fitness education, and career development. It also serves adults with career services, entrepreneurial development, and GED and ESL support. They are also working with ESPN to fund conversion of vacant lots into play spaces for children.

Additionally, the company has organized several “all Baltimore” runs in the past year, in an attempt to bring all the running groups of the city together. Leading up to the 2018 Baltimore Running Festival, the company asked local running crews, including RIOT, to design and host runs throughout different parts of the city, with free gear giveaways to those who showed up. The runs served as a way to show off parts of the city outside the white L most runners never see, and gave exposure to the diversity that exists within the running scene.

While headway is being made, like so many things in Baltimore, change comes slowly. It may be in five years, or it may 50, but runners like Clapp and Olufemi hope that in time, the L will lose its edges, and the butterfly wings will fold into themselves.

“There’s gonna be more people joining, more people picking up as they see more and more black runners,” says Clapp.

Late September last year, on the first break from what seemed like months of humidity, Clapp showed up with RIOT to lead one of Under Armour’s crew runs in northern Baltimore. It was a Sunday recovery run that started in Belvedere Square, outside the typical running zones in the L. The run included a free shoe giveaway from Under Armour. It drew around 30 people, mostly black. Aside from the group, no other runners were seen on the route. But there were 30 where there were none before, being seen and etching new lines on the heatmap.

Robbe Reddinger is the Senior Editor for Believe in the Run, a run media company focused on shoe and gear reviews. He's been nicotine-free since April 1, 2023. He loves running around his home city of Baltimore and spending time with his wife and two boys.