Watch Scientists Melt a Satellite Part to See How Stuff Burns Up During Reentry

European researchers melted a dense satellite part in a special space fire created in a lab in hopes of better protecting people on Earth from falling debris as satellites re-enter our atmosphere.

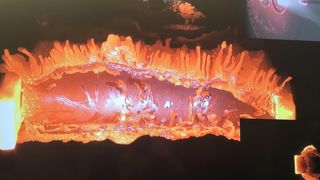

A new video shows a 2-inch by 4-inch (5-centimeter by 10-centimeter) instrument called a magnetotorquer dramatically turning to liquid inside of a plasma wind tunnel. This facility at the German Space Agency (DLR) in Cologne, Germany, simulates the superheated gas (or plasma) that satellites experience during re-entry. By the time the test was over, the instrument had been exposed to temperatures of several thousand degrees Fahrenheit (or Celsius), and was transformed into vapor.

The research is vital to help scientists understand how satellites fall apart during their descent to Earth; most pieces usually burn up in the atmosphere, but occasionally something survives and plunges to the surface of our planet.

Related: If NASA's Satellite Falls on Your Home, Who Pays for Repairs?

The most notorious incident was NASA's Skylab space station, fragments of which unexpectedly rained down over rural Australia in 1979. Other incidents followed: In 1997, for example, Texans Steve and Verona Gutowski woke up to a large noise and discovered something that looked like "a dead rhinoceros" only 165 feet (50 meters) from their farmhouse. The item was actually was a 550-pound (250-kilogram) fuel tank that fell off a spent rocket stage, the European Space Agency said in a release published with the new video.

"Modern space debris regulations demand that such incidents should not happen. Uncontrolled reentries should have a less than 1-in-10,000 chance of injuring anyone on the ground," the statement reads. "As part of a larger effort called CleanSat, ESA is developing technologies and techniques to ensure future low-orbiting satellites are designed according to the concept of 'D4D' — design for demise."

Hence the satellite campfire. ESA is deliberately testing satellite parts that are prone to survival in order to better design them for a fatal breakup. Magnetotorquers, which use the Earth's magnetic field to align satellites, are one of the most robust satellite parts. Other examples include optical instruments, propellant and pressure tanks and the drive mechanisms for gyroscopes (reaction wheels) or solar arrays.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In particular, ESA is hoping to learn how to prevent these parts from simply breaking up, since more pieces of debris means more chances of hitting something or someone. Instead, the agency hopes to build parts that safely and completely burn up long before they approach Earth's surface.

- How Much Space Junk Hits Earth?

- Space Junk FAQ: Falling Space Debris Explained

- Biggest Spacecraft to Fall Uncontrolled From Space

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace