by Sophie Novack

April 23, 2019

UPDATE: Rhonda Hart lost the school board race on May 4 with 33 percent of the vote, but she continues to advocate for gun violence prevention and says she’s not giving up on politics. “It’s not my last race, but I need to recover from this one,” she told the Observer the day after the election.

It’s happened a few times now: A reporter reaches out to Rhonda Hart. They send their condolences. They want to talk to Hart about her daughter, who was killed by a fellow student in a shooting at her high school last year. “They’ll say, ‘Oh Ms. Hart, I heard your story and I’m so sorry for your loss,’” Hart says. “‘And by the way, I’m coming to Parkland, would you like to do an interview?’”

Hart says no. She doesn’t live in Parkland. Her 14-year-old daughter, Kimberly Vaughan, was killed in the shooting at Santa Fe High School in Texas last May 18 — not in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, just three months before.

“You have the wrong family. You have the wrong event,” Hart tells them. “That’s usually kind of a deal breaker,” she says, shaking her head. “[It’s] terrible that we can’t keep our shootings straight, because they’re so close together. You know, it’s just one after the other.”

It’s a telling mistake. The Santa Fe shooting, in which 10 people were killed, didn’t get the same attention as the one in Parkland, where students started the March for Our Lives movement to end gun violence. Santa Fe is gun country. The rural town about 35 miles southeast of Houston went for Trump by 80 percent in 2016. The small pub in the center of town has two flags out front: American and Confederate. This legislative session, Santa Fe families have traveled to Austin to speak in favor of bills beefing up school security. Nearby, Texas City ISD has spent more than $5 million in the last year on 22 AR-15s, sheriff’s deputies, surveillance cameras and student tracking devices. But when it comes to calls for gun law reform, the response from many in the area has been muted, even oppositional.

Hart, who drove a school bus for Santa Fe ISD for four years until Kimberly was killed, feels like an outsider. A U.S. Army veteran, Hart has become a vocal advocate for gun violence prevention, traveling to Washington, D.C., with Moms Demand Action to support red flag laws, responsible gun storage and other measures. Former Congressman and 2020 presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke has given her shout-outs at rallies and carries a photo of Kimberly in his wallet. In February, Hart attended the State of the Union as Houston Congresswoman Lizzie Fletcher’s guest. She’s made friends with Parkland families and other shooting survivors across the country. (“All my new friends I’ve met lately are through gun violence. And they’re the coolest people ever,” she says, but, “you know, it’s morbid.”) Just after Kimberly died, she and her 12-year-old son Tyler moved to the next city over; they rarely return to Santa Fe.

“[It’s] terrible that we can’t keep our shootings straight, because they’re so close together. You know, it’s just one after the other.”

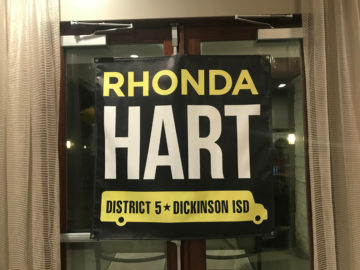

Early this year, Hart decided to channel her pain into a run for school board at Dickinson ISD, where Tyler is enrolled. It’s her first campaign for office. She’s running against incumbent Board of Trustees member Corey Magliolo, a business owner who ran unopposed for the spot in 2016. The election is on May 4, or as Hart calls it, “Star Wars day.” When she announced the date at her campaign party last month, Tyler, wearing a Yoda T-shirt, cheered: “Mayyyy the fourth be with you!”

“A lot of people think, ‘Oh it’s just school board, oh it doesn’t matter.’ But your little boards — your community college boards, school boards, city council, mayorship — that’s where your first line of defense in your democracy is,” Hart said at the event.

Hart’s short light brown hair still has traces of the highlights she dyed bright red, Kimberly’s favorite color. Hart says her dad, who is bald, kept his nails painted red for six months in honor of his granddaughter. Those close to her wear a silver charm of “I love you” in sign language, which Hart calls the family emblem. It was the last thing she said and signed to Kimberly, after she parked her bus in front of the high school that morning. About an hour later, her daughter was killed.

The memory of Kimberly — a Girl Scout who loved books, Harry Potter and cats — keeps Hart going: “Go forward. Make a positive change. Do something with this grief.” Sometimes Hart hears her daughter cheering her on: “Like, ‘yeah that’s my mom, go get it!’” Hart laughs. “I think she’d kick my butt if I didn’t do anything. … She wouldn’t want me to just sit here and wallow.”

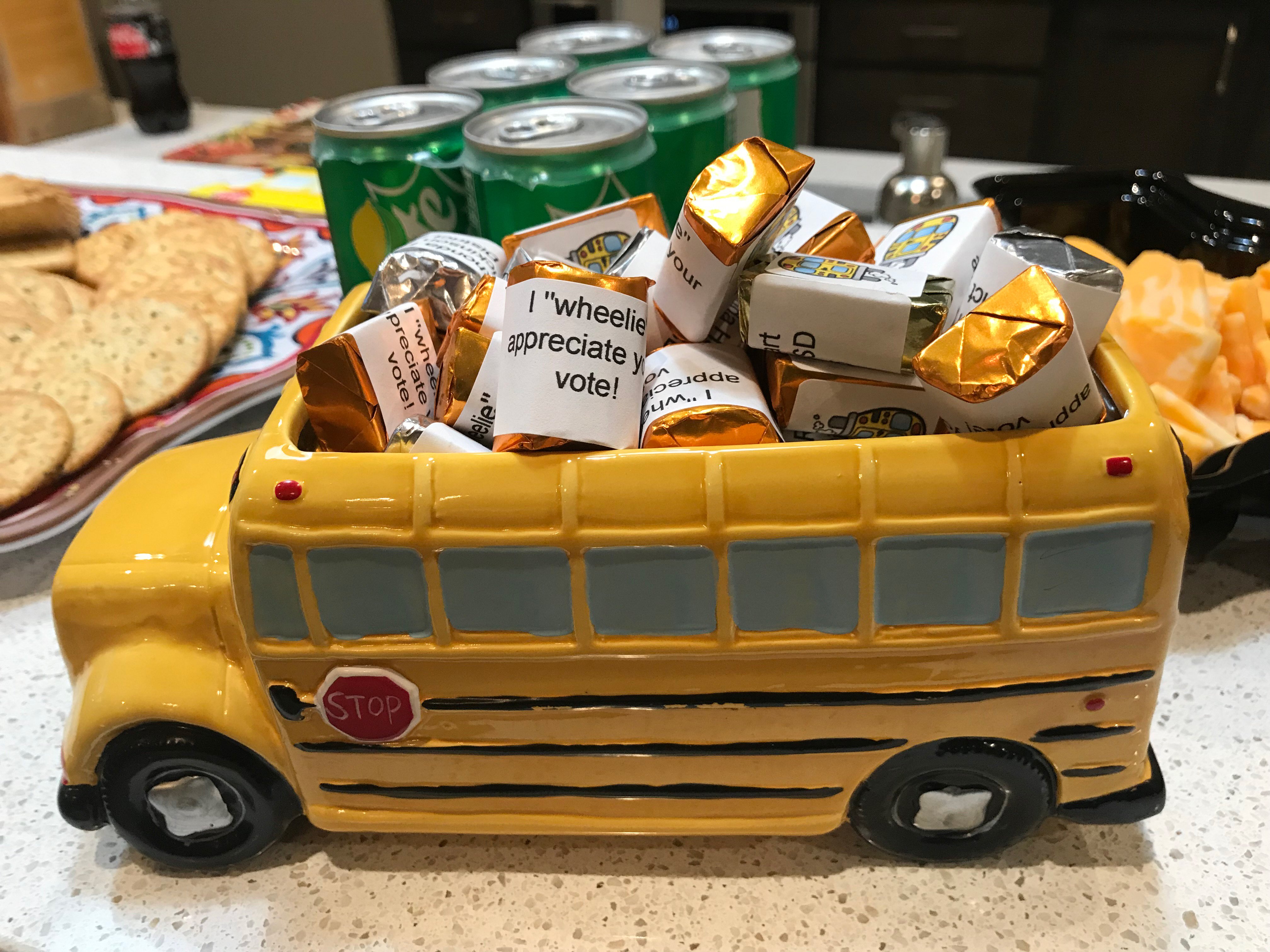

Before her campaign kickoff event, Hart and a few friends stood in the meeting area of her new apartment complex, arranging snacks on yellow plates. Tyler taped paper school buses to the walls for the party’s theme. A handful of supporters from across Galveston County would soon arrive for the launch of her campaign, which focuses on her work with kids and commitment to school safety. “I’ve always wanted to throw a school bus party,” she told me with a grin. A ceramic school bus was filled with Hershey’s chocolates wrapped in paper with the words “I ‘wheelie’ appreciate your vote!” Her slogans: “Driving Change” and “Vote with Your Hart.”

The new apartment is a 15-minute drive from Santa Fe — just enough separation, Hart says. It’s a familiar drive, since much of it follows Hart’s route as a school bus driver. After she left, families along her bus route put out lawn signs reading “We love you, Rhonda.” Today, most of those are gone.

At the high school, it appears not much has changed. “Santa Fe Strong” is painted across the glass windows near the entrance in yellow and green block letters, right after a reference to the football team: “Home of the Santa Fe Indians.” On the front lawn is a white sign, worn by weather and folded over by the wind: “FUTURE SANTA FE STRONG MEMORIAL.” Around town, the “Santa Fe Strong” slogan still peppers lawns and storefronts, and is emblazoned on police cars and T-shirts.

“I thought people would change their minds after Parkland, I thought people would change their minds after all those other shootings,” Nick Robertson, who graduated from the high school in June, told me at Hart’s campaign party. “Then after the Santa Fe shooting I thought: Well this hit too close to home, there’s no way that they can not change their minds. But a lot of people didn’t. A lot of elected officials didn’t.”

Robertson, who grew up in Santa Fe, was running late to school on the morning of the shooting. A friend called to warn him not to come; otherwise he would have been in the hallway by the art classroom where Kimberly was shot. Robertson said he grew up with guns in his family, but has always believed in what he calls “common sense gun control”: background checks, red flag laws, making sure guns don’t get in the wrong hands.

“What’s frustrated me the most is the lackluster action,” he said. “I’ve used the word ‘frustrated’ like 14 times,” he said, laughing. “That’s what I felt after the shooting: How can this happen and you still hold the same views you had before it happened?” He added, “There are things we could do about this…”

“Thoughts and prayers will not stop a bullet,” Hart interjected with a heavy sigh.

Hart doesn’t talk much about the shooting unprompted, but Kimberly is everywhere, from her decision to run for office to their basset lab mix that Hart calls the “official campaign dog.” They meant to just foster Mario when they took him home from a shelter on January 18, exactly seven months after the shooting. They ended up adopting him. Hart calls it divine intervention. When they brought him home, Hart recalls watching as Mario walked over to the urn with Kimberly’s ashes on a living room table. She was scared he’d knock it over. Instead, he sniffed the container and turned to her with a knowing look. “Okay that’s it, we’re keeping the dog!” Hart remembers thinking.

“She wouldn’t want me to just sit here and wallow.”

They’re teaching him Harry Potter spells. “Descendio,” Tyler said, showing me, and Mario sat. Hart says having the dog has given Tyler, who’s been struggling since Kimberly’s death, a reason get out of bed in the morning.

For a while after the shooting, Hart home-schooled her son. Sending him back to school was a difficult decision, one they both think about every day. “A lot of parents are worried about the grades and the attendance, and I was one of those people. Now my standard is: Do I get to pick up a kid at the end of the day?” she said. “I just want my son in one piece. That’s what we’ve come to now, and that’s what I’m trying to change.”

Hart says she’s gotten negative feedback during her campaign from people who think she’s trying to take their guns. “I can’t, I don’t want to,” she said. “Just, let’s stop shooting each other?” Her school board platform is broad: lowering the stakes of standardized tests, a living wage for teachers, supporting special-needs families. And, a big one: school safety, which Hart is quick to say goes way beyond guns to include class sizes, building maintenance and making sure the school bus fleet is safe and well-maintained. “Look, I’ve always had this mindset of safety, keeping kids safe on a 23,000-pound vehicle,” she said. “[This is] just protecting them on a different level.”