Citing chronic underfunding and excessive workloads, East Baton Rouge Parish's chief public defender sought permission Thursday to withdraw from some cases and decline future appointments, even if it results in charges being dismissed against indigent defendants.

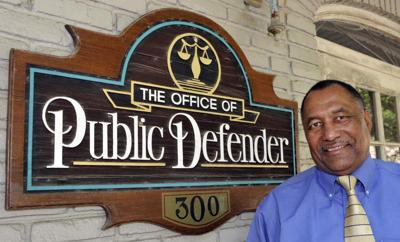

Public defender offices statewide have complained they don’t have adequate resources. In the 19th Judicial District, Mike Mitchell’s plea applies only to cases before state District Judge Don Johnson, but the public defender said the seven other criminal courts in East Baton Rouge Parish have similar problems.

"Every section is as overloaded as this section," he said. "We are at significant risk of providing ineffective assistance of counsel in some of our cases." Defenders there would have to make their own pleadings.

Mitchell in 2015 lost funding for six attorneys, an investigator and an administrator.

With about a third of annual state funding for public defense going to private law firms representing clients facing capital murder charges, L…

If Johnson grants Mitchell's request and a different public defender or other competent lawyer cannot be found to represent affected indigent defendants on Johnson's docket, a motion filed by Mitchell's attorneys asks the judge to dismiss their cases and release them from custody.

During a break in a daylong hearing on Mitchell's motion to withdraw from some current cases and decline future appointments, Mitchell acknowledged that such dismissals would be without prejudice, meaning the East Baton Rouge Parish District Attorney's Office would be able to refile the charges later. Speedy trial requirements under the Constitution could still apply, though defendants could waive them or the prosecution could demonstrate a legitimate need for more time, parish prosecutors said.

A year after instituting a hiring freeze to cope with a mounting funding crisis, East Baton Rouge Parish’s chief public defender said Monday h…

At the start of the hearing, Assistant District Attorney Mark Dumaine said the judge could not grant Mitchell’s request because court funding is an issue that only the Legislature can resolve.

"You don't have the power to give them the remedy they seek," Dumaine said. "They remedy they seek is not the law."

Maggie Broussard, one of Mitchell's attorneys, disagreed and said Johnson can and must step in to prevent the public defenders in his court from violating their constitutional and ethical obligations to provide effective assistance to their indigent clients.

John Landis, who also represents Mitchell, said the excessive workloads also are exposing Mitchell's public defenders to potentially violating the Louisiana Rules of Professional Conduct for lawyers.

Johnson, who will hear additional evidence in the case Friday and in the coming weeks, said he would rule on the state's dismissal request and on the merits of the case later.

Depending on how Johnson or appellate courts rule, Mitchell said he may file similar motions in other criminal sections of the 19th JDC. Mitchell said he filed the motion in Johnson's court after personally observing some defendants complaining in that court that they had never met their public defender.

Mitchell's motion cites a 2017 report by the accounting firm of Postlewaite & Netterville and the American Bar Association, which was commissioned by the Louisiana Public Defender Board, that found the full-time public defenders in Mitchell's office have the capacity to handle only about 34 percent of their annual workloads if they each devoted no more than 2,080 hours annually to their caseloads. Those hours represent 40 hours a week over 52 weeks.

Statewide, public defender offices have blamed funding shortfalls on drops in fines and fees on traffic citations. Louisiana is unique across the country in financing much of its public defense through court costs paid by the guilty.

Public defense funding in Louisiana must be spared the state budget ax, the president of the American Bar Association stressed this week in a …

Mitchell's office also receives funding from the state public defender board.

Mitchell, who has served as East Baton Rouge's chief public defender for a quarter-century, testified Thursday that his office has been in a fiscal crisis since 2015 when he was forced to eliminate eight positions.

Dumaine pointed out that years ago there were only two public defenders in each of the 19th JDC's eight criminal sections, for a total of 16, but now there are 27 -- four in three of those sections apiece and three each in the rest. The prosecutor, while questioning Mitchell, said Mitchell's office has "more legal horsepower" than ever before.

Mitchell replied that his office represented between 12,000 and 13,000 people last year.

"We're drowning," he said.

Dumaine asked if any of Mitchell's staff attorneys are currently providing ineffective assistance to their court-appointed clients.

"That is exactly what we're trying to avoid," the chief public defender replied.

Mitchell stressed that he's not saying the East Baton Rouge District Attorney's Office shouldn't have more attorneys as well.

"Well, thank you," Dumaine said with a grin.

Mitchell said his office expects to close the current fiscal year that ends June 30 with a $285,000 deficit, but he said the state public defender board will cover that shortfall.