A University’s Betrayal of Historical Truth

The University of North Carolina agreed to pay the Sons of Confederate Veterans $2.5 million—a sum that rivals the endowment of its history department.

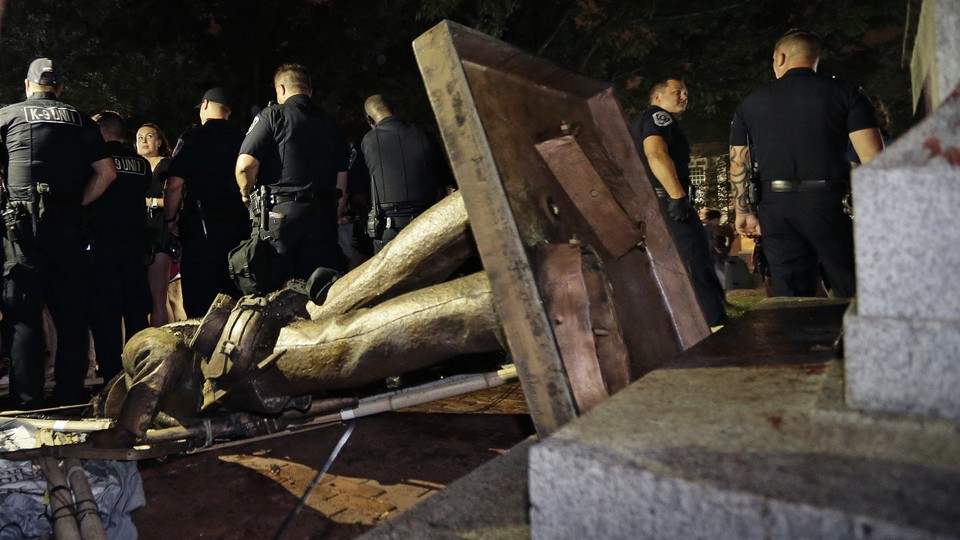

On the eve of Thanksgiving, the University of North Carolina Board of Governors agreed to settle a lawsuit filed by the North Carolina division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) over a Confederate monument that had stood for more than a century on the university’s flagship campus, in Chapel Hill, before demonstrators toppled it in August 2018.

The settlement might, at first glance, appear to be a workmanlike solution to a vexing issue. It ensures that the monument, commonly referred to as Silent Sam, will no longer adorn the university campus. Under the terms of the consent decree, the SCV will take custody of the monument and receive $2.5 million in “non-state funds” for a “charitable trust” to care for it. In a statement to the UNC community, which for more than a decade has been riven by the controversy over the monument, UNC Interim Chancellor Kevin M. Guskiewicz applauded the Board of Governors for “resolving this matter.”

The settlement, though, establishes a de facto financial partnership between the university system and the SCV to preserve the monument. The SCV is free to use Silent Sam and this generous subsidy to continue its long-standing misinformation campaign about the history and legacy of the Civil War, with an endowment that rivals that of the university’s history department. But the cost to the university can’t be fully tallied in dollars and cents. A great public university should stand for the pursuit of truth, not the promotion of historical distortions and falsehoods. In seeking an expedient solution, the university system has succeeded only in aggravating the problems that the removal of the statue was supposed to address.

The Sons of Confederate Veterans traces its roots back to 1896. Members pledge to honor their “heroic” Confederate ancestors by perpetuating their “glorious heritage of valor, chivalry and honor” and instilling in their descendants “reverence for the principles represented by the Confederate States of America.” For its first eight decades, the SCV was overshadowed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a national network of women’s memorial associations that took the lead in honoring all things Confederate.

But during the 1980s, the SCV was reborn in response to an increase in the perceived threat to its traditional narrative, its membership growing to about 30,000, spread out over roughly 800 local camps. Until then, the SCV’s embrace of a largely mythical Lost Cause narrative that celebrated Confederate generals as Christian warriors, rank-and-file soldiers as defending a noble cause rooted in a constitutional defense of states’ rights, and its denial that slavery had anything to do with the war remained largely unchecked in much of the South. The SCV dismissed new scholarship that emphasized the centrality of slavery and emancipation to the war, as well as the roughly 180,000 African Americans who fought in the United States Army, as politically correct “revisionism.” Indeed, the SCV became the modern voice of the Lost Cause as a racial ideology, which in its origins and well through the Civil War centennial in the 1960s celebrated the ties of Confederate soldiers and their descendants as the friends and protectors of “faithful slaves” and their descendants.

But the SCV has increasingly found itself on the defensive. Historic sites and museums, including the Museum of the Confederacy, in Richmond, Virginia, have devoted exhibits and programming to the tough questions surrounding the Confederacy’s defense of slavery and white supremacy. In 2007, North Carolina’s General Assembly passed resolutions formally apologizing for the institution of slavery in the state. Bruce Tyson, the SCV’s state commander, denounced the resolution’s condemnation of the injustice, cruelty, and brutality of slavery. “Although some of our ancestors did own slaves,” he said, “there is no evidence in most cases that they were ‘cruel’ or ‘brutal’ toward their slaves, nor that our ancestors were, in general, racist.”

Such statements not only defy enormous historical evidence; they parrot the claims made by Jefferson Davis and hundreds of other prominent Lost Cause spokesmen in the late 19th century who attempted to embed into the American imagination the idea that white southerners had never really fought for slavery, even while they kept African Americans as a race under paternalistic care and control.

In their effort to defend the integrity of their ancestors, SCV leaders embraced the myth that thousands of enslaved men fought as soldiers in the Confederate army. By the 1990s, hundreds of websites—many promoted by the SCV—helped spread stories of brave black soldiers fighting side by side with their white comrades in defense of a shared “southern homeland,” a claim that flies in the face of historical evidence.

The SCV simultaneously sought allies for its campaign to defend “southern heritage.” An activist wing of the organization embraced the League of the South, a white southern nationalist organization committed to the establishment of a white Christian nation, and flirted with various avowed white nationalists. By 2005, after more than a decade of campaigning, the activists were in firm control of the SCV.

Relatively few people paid attention to these heritage wars until the brutal murders of nine churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, in June 2015. The publication of photographs of Dylann Roof posing with a Confederate flag led to the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the South Carolina–statehouse grounds. The SCV attempted to minimize the damage by trotting out the Lost Cause narrative and the black Confederate myth: “These brave black men fought in the trenches beside their White brothers, all under the Confederate Battle Flag.” Once again, the SCV found it difficult to hold the line as cities and towns across the South began to debate whether to remove Confederate monuments, or in some cases actually removed them. The debate over Confederate monuments, locally and nationally, has been the source of useful cultural tension as well as perhaps cleansing. But the SCV’s position about the origin and purpose of such monuments has only buttressed the worst elements of Lost Cause ideology.

After the Southern Baptist Convention issued a resolution in 2017 condemning the display of the Confederate battle flag, North Carolina’s SCV again voiced its outrage: “We . . . strongly oppose this resolution and the treasonous insult it is to the soldiers who fought for freedom from Federal tyranny that we still face today.” That the SCV feels emboldened to charge treason against those who urge a serious reckoning with fact-based, careful, scholarly history about these most divisive issues in our national past says a lot about this historical moment.

More recently, the group’s North Carolina division commander advocated for the erection of more Confederate monuments and traced the campaigns to remove Confederate monuments to “small, hard-core Communist groups like the Workers World Party in Durham—the same group that cheers on Kim Jong Un in North Korea.”

The SCV’s defense of the legacy of the Confederacy has largely failed, but the $2.5 million payout from the UNC system will allow the group to continue to promote a false view of history that pushes us further from understanding one of the most crucial periods in American history.

The deal struck by UNC stands in sharp contrast with the approaches taken by other universities that have grappled with difficult chapters in their institutional history. Georgetown University has undertaken tangible commitments to compensate descendants of slaves auctioned by the university before the Civil War. Furman University, in South Carolina, is engaged in an ambitious redesign of everything from its campus to its curriculum in acknowledgment of its role in past social injustices. The University of Texas at Austin created a commission to address the presence of Confederate monuments on its campus, and decided to remove statues of Generals Robert E. Lee and Albert Sidney Johnston. Yale, after a careful study, decided to rename the John C. Calhoun residential college on its campus. Meanwhile, the UNC system has chosen to bankroll a Confederate heritage organization.

At the very least, the flagship campus, at Chapel Hill, where Silent Sam formerly stood, has a moral and intellectual obligation to divorce itself from the Board of Governors’ decision to subsidize the SCV. Failure to do so will make it difficult, if not impossible, for the university to distance itself from the SCV’s distorted version of history.

The Board of Governors and university administrators who negotiated this settlement were looking for an expedient solution. The university is already struggling to overcome a recent scandal involving student athletes, and trying to complete its largest-ever fundraising campaign. By paying the SCV the equivalent of hush money and transferring the embattled monument to the organization, the university system may have hoped to wash its hands of an unwelcome issue. In the process, the university has made historical truth secondary to burnishing the university’s brand and managing the message.

But the UNC leadership cannot wash its hands of the past. The university’s archives hold thousands of documents that demonstrate the depth of the Lost Cause tradition and illuminate the era of Jim Crow in which the Silent Sam monument was erected. In one of those documents, from 1929, a North Carolina woman, Bertha Lucas Smith, claimed that the slaves at her family plantation in New Hanover County had been “a happy and contented lot.”

“Life held all happiness,” it seems, until the war came, when in its final year, “every male slave except old Uncle Jim left my Father to join the Yankee forces.” The fleeing former slaves desecrated the old place, Smith said, by stealing their master’s special box of papers because they thought it contained money. She remained incredulous all those years later at the slaves’ lack of “loyalty.”

This is the sort of flawed history that Silent Sam was erected to enshrine. But instead of directing its largesse to the descendants of those who were enslaved, the university chose to give its millions to apologists for their enslavers. “What we have accomplished is something that I never dreamed we could accomplish in a thousand years,” the SCV’s North Carolina leader emailed his members, “and all at the expense of the University itself.”