How a City Talks About Itself: Sioux Falls

In June 2013, my husband, Jim, and I first landed our small, single-engine Cirrus propeller airplane at the main airport, Joe Foss Field, in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

It was the first stop on our American Futures project, and we were excited and a little nervous wondering what we might find—if anything—to explore and write about there.

We learned about the waves of refugees and immigrants, and their children who made up nearly 10 percent of the school system and spoke more than 60 languages. We learned about the John Morrell packing plant, where Muslim women slaughtered pigs all day, keeping the plant in business and establishing an economic beachhead for their families. And the USGS-EROS site, which captured, downloaded, and stored the entire country’s satellite imagery every 90 minutes, day in and day out, over the decades. And Raven Industries, which developed and manufactured precision-agriculture equipment and made balloons for the Macy’s Thanksgiving parade.

We met nurses who had moved to Sioux Falls from all over the region to study and practice, and with their “Midwest nice” treated us to a beer at the Granite City brewery when they learned it was our anniversary. We rode bikes on the path that circled the city, passing again the airport, the state penitentiary, and downtown area and falls and many fields where the New Americans played soccer.

Our initial gee whiz reaction to Sioux Falls sprang from the multitude of the town’s endeavors and the loftiness of its citizens’ dreams. How could so much be going on in one town that we had barely heard of before? Little did we know that after visiting 10 or 30 or 50 more towns around the country, we would come to expect similar ventures, or more accurately, local versions of them, as we grew to admire the creative energy that so many Americans poured into their hometowns across the country.

More than five years and 100,000 miles later, Sioux Falls became the first city we wrote about in our book, Our Towns. We returned again a few weeks ago with an HBO film crew, for a documentary scheduled to come out next year. With them we wanted to see and document how the town had changed, to revisit some of our favorite places, and to discover new ones.

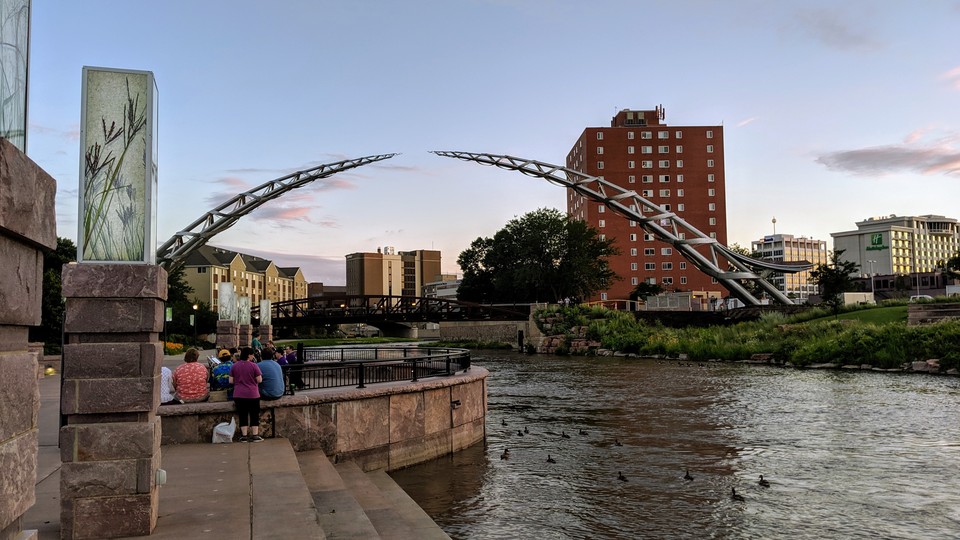

Once again in Sioux Falls, we found a more mature, nuanced town. Some early initiatives had come to fruition, like the expanded sculpture walk and the capstone of sculpture, the gallant Arc of Dreams, which soars across the Big Sioux River. Or the additional blocks and blocks of new restaurants, bars, shops, and hip lofts stretching down the main street. Others remained a work in progress. Some problems, opioid addictions above all, were much more front of mind, proof that Sioux Falls was in sync with the rest of America.

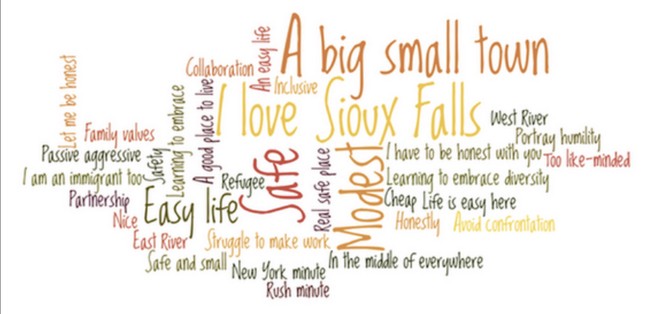

After our first visit in 2013, I made a word cloud of words and phrases that I heard around Sioux Falls that struck me as reflecting the spirit of the city. After our latest visit a few weeks ago, I made another. You can compare and contrast, as college teachers of my generation used to say. Here is the first one:

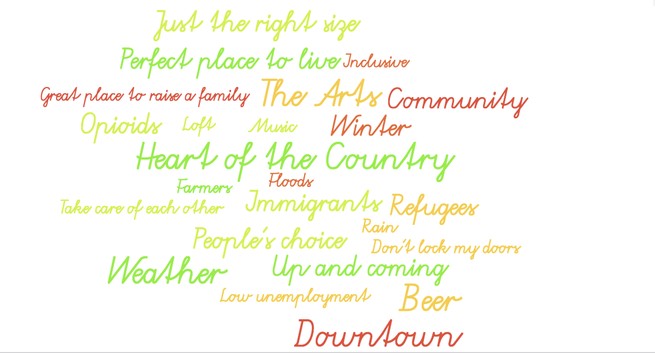

And here is the one I’ve made just now, after our latest visit:

What are my takeaways of Sioux Falls now? These are the main themes I heard so often that they made their way into my word cloud.

Heart of the country: When the residents of Sioux Falls describe this sentiment about their city, they are describing its spirit even more than its geography. Many people offered some version of this comment in an uncynical, unabashed way. Sioux Falls is the perfect place to live. Others took it even a step further: “There is nowhere else in the world I would live,” a transplant from Winnipeg told us. (We understand all the reasons why people might differ. I’m just reporting what we heard while on-scene.)

What are the attributes of this sentiment? Just the right size is one description we heard frequently. Curiously, many other people across the country describe their hometowns the same way, whether they lived in towns of 1,250 or 25,000 or like Sioux Falls, just shy of 200,000. Behind the idea of just the right size is “big enough that there is a lot going on, and small enough that I can have some impact here.”

Sioux Falls, adults frequently say, is a great place to raise a family, and those who moved there or returned say that the quality of life for families played a big role in their settling in Sioux Falls.

Low unemployment: The current unemployment rate, almost always lower than the national average and now around 2 percent, is a big attraction of Sioux Falls, although that is complicated by the very low average wage. (How can both these things be true—demand for labor going up, but wages staying down? We asked everyone we met, and the answers were variations on “it’s complicated.” I will let Jim discuss this further in another post.) The John Morrell plant, as it is still called, was purchased by Smithfield in the 1990s, and subsequently by the large Chinese firm Shuanghui in 2013. It has remained a steady fixture for reliable jobs, particularly for the immigrant population. We saw again Muslim women who had been working in the plant, shaving fat from the slabs of pork, for over a dozen years by now. They have moved with their families to suburban-feel streets, with bigger houses and spacious lawns.

Don’t lock my door: Several people bragged on this measure for houses and cars, in what was a proxy for a safe place, and that we take care of each other.

Going around town on a hot summer day shows off the sports, recreation, and the good lifestyle of Sioux Falls: gaggles of kids in team-colored T-shirts at golf camp or riding their bikes to the neighborhood pools. I swam in the 50-meter pool at the new Midco Aquatic Center. I visited libraries where summer tutoring programs were keeping kids on track or bringing them up to speed in reading skills. The 20-mile circuit around the river was busy with bikers, joggers, and walkers.

Weather: South Dakotans are a tough breed, but this past winter, with many dozens of days that didn’t break zero degrees Fahrenheit, challenged even these hardy folks. Most brought up the long, endless winter, followed by the rains that flooded farmers’ fields, halting planting or at least slowing crops. We saw fields that never got a chance, and fields of corn that were yet to show tassels. A violent hailstorm finally broke the wilting upper-90s heat during mid-July, insulting further by flattening some waist-high cornfields entirely. This year at least, it seemed that the farmers just couldn’t win. One farmer told us that normally the July rains would be considered a miracle, but this year, they only brought more heartache.

Floods roared down the Big Sioux River, ripping concrete caps off the riverwalk walls and buckling roads, which demanded weeks of road repairs.

Community: I found the references to community most complicated. Sioux Falls reflected its German and Scandinavian heritage with the tall, light haired population that settled this territory after displacement of the Native American tribes, who now fight hard to preserve their cultures and languages on the reservations. Tall, blond people are everywhere. But so are immigrants, refugees, and Native Americans. Refugees have been welcomed to Sioux Falls through Lutheran Services resettlement programs since the 1970s. (The numbers have been dropping. In 2015, about 500 refugees were settled in South Dakota; in 2017, with cuts in refugee resettlement by the Trump administration, those numbers dropped to about 300; in 2018 to about 200.) In addition to primary resettlement, many of the self-described New Americans now arrive in a wave of secondary migration; word has gotten around to friends and relatives around the country that Sioux Falls is a pretty nice place to be, with opportunity to build a good life—despite its weather.

One of the worst realities of Sioux Falls, and for nearly all of the U.S. that we have seen, is opioids. That word was new to the voice of Sioux Falls. We stepped around the muddy construction lot of the new residential addiction-care center at Avera Health, which is about to open with 32 private rooms. (We also saw flashing billboards of the Farm and Rural Stress Hotline, also manned by Avera Health, which is another of Sioux Falls’s answers trying for traction against spillover of the farmers’ woes.)

Up and coming + the arts: When we first visited Sioux Falls in 2013, we heard buzz about “the arts” in many conversations. On this visit, some 6 years later, we have seen and appreciated the results. Each year now, residents of Sioux Falls vote for their favorite sculpture among the many lining downtown Phillips Street for the city’s Sculpture Walk. The city purchases the winning entry, and the rest move along, making way for next year’s rotation of new installations.

Sioux Falls has a distinct democratic bent, heard in the term People’s Choice. That’s how the city’s annual sculpture for purchase was selected, and the name for the new Thomas Jefferson High School, and the name for the Oak View public library, and the design for the new city flag, which Mayor Paul TenHaken showed us with great enthusiasm. “Democracy runs deep in the Midwest,” one resident explained to me.

The town was chattering about the free outdoor summer concerts at the Levitt shell downtown. The Siouxland public library sponsored a Reading Invasion, and people showed up an hour before the concert to stake out their spots on the grass, and—wait for it—to read to themselves or their children. Jazz Fest was in full swing. The numerous brewpubs were full. We joined the Pork Crawl put on by the South Dakota Pork Producers Council. The Washington Pavilion was showing off its combination of the arts and science museum, housed in the renovated, stately former Sioux Falls (then renamed Washington) High School. New art exhibits were being assembled, and I would say that the science museum for kids is the best that I’ve seen.

The Falls, of course, are nature’s contribution. Its surrounding park hosts one of the most diverse collections of Sioux Falls citizens as anywhere in town. Latino families picnic nearby. Young Somali men move elegantly from boulder to boulder. Just upstream, South Dakota artist and sculptor, Dale Lamphere, whom we met at the base of his new installation, the Arc of Dreams, explained that its soaring arch represents the dreams of the people of Sioux Falls, and its 18-inch gap at the center where the two sides of the arch would meet—but don’t—represent the leap of faith that must finally be made by the dreamers who settle and live there.