What It Means to Name a Forgotten Murder Victim

Thirteen years ago, a young woman was found dead in small-town Texas. She was nicknamed “Lavender Doe” for the purple shirt she was wearing. Her real identity would remain a mystery until amateur genealogists took up her case.

The dead girl had perfect teeth.

That’s what so many of the strangers who obsessed over her case online noticed, and one of the few things that could even be noticed. Her body was burned so badly as to be unrecognizable when she was found in the early hours of October 29, 2006, near Longview, Texas.

The two men who saw her thought, at first, that they had stumbled across a mannequin set on fire, perhaps as an early Halloween prank. It was the smell that alerted them to something more sinister in the woods—a smell like charred hot dogs. When they stepped closer, they realized the awful and obvious truth. A human being had been killed, then doused in gasoline and set on fire, and probably only minutes before: Her body was still ablaze.

When law enforcement came, the officials began making note of the few facts that would come to encompass her entire identity. She was young, between 17 and 25. She had semen inside her. She had blond hair with strawberry highlights. There was $40 in the pockets of the clothes she wore, a pale-purple shirt and jeans, size 7-8, branded One Tuff Babe. “Sadly ironic, considering her fate,” a commenter remarked on the true-crime discussion forum Websleuths. That same commenter would later give her a nickname of “Lavender Doe”—chosen for the color of her shirt.

Days passed, then weeks, and then years. No one who knew her name ever came forward. No friends or family called the sheriff’s office in Texas. No one filed a missing-person report. Lavender Doe, bestowed by an online stranger, was the only name she had.

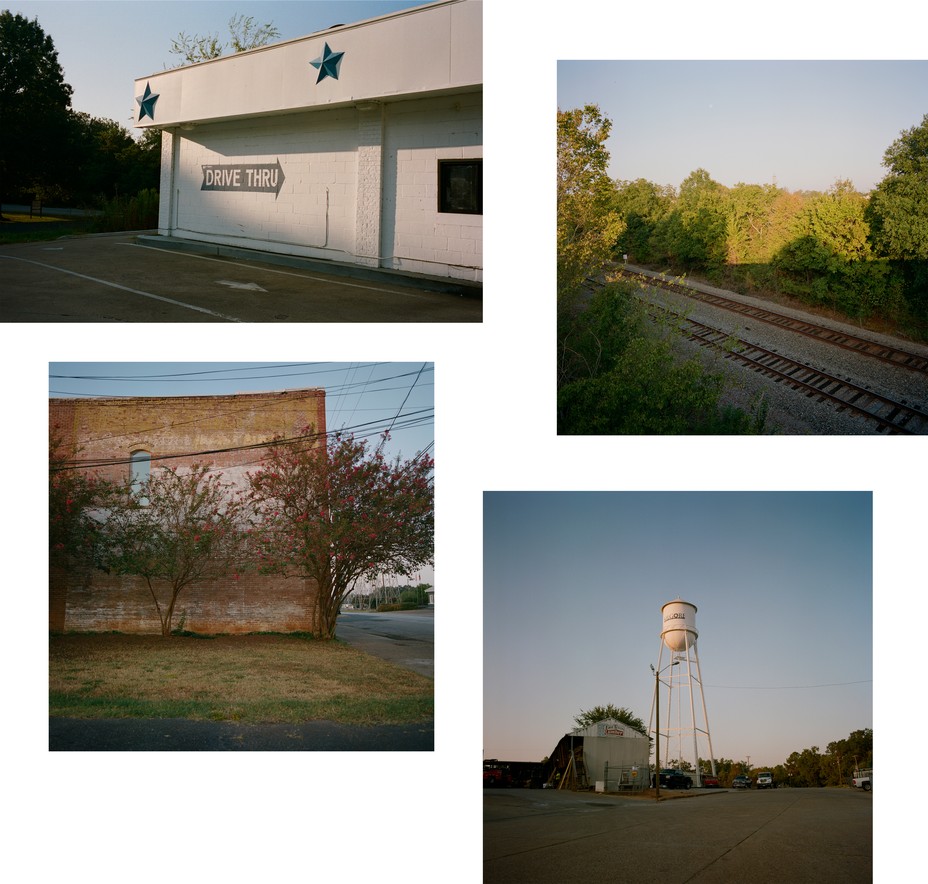

This past November, 12 years and a month after she was found dead, I went on a road trip to Longview, Texas, with volunteers who believed they had just uncovered Lavender Doe’s real name. Seven months earlier, a genetic genealogist had led police to a suspect in the infamous Golden State Killer case, and volunteer genealogists with a fledgling nonprofit called the DNA Doe Project had helped Ohio law enforcement identify a murder victim previously known only as the Buckskin Girl.

Cold cases have always attracted amateur sleuths—and psychics and self-proclaimed forensics experts—often to the irritation of actual law enforcement. Genetic genealogy is different: It works. Once this combination of traditional genealogy and DNA tools led to the arrest of the suspected Golden State Killer, the floodgates opened wide. Self-taught genealogists were helping police identify criminals and victims almost by the week. Suddenly, it seemed, anyone with the right savvy and an internet connection really could solve cold cases from their living room.

The three genealogists I met in Texas were all volunteers for the DNA Doe Project: Kevin Lord, a 35-year-old with scraggly black beard then studying to be a private investigator; Missy Koski, 55, a “search angel” who helps other adoptees find their birth parents; and Lori Gaff, 49, a genealogy enthusiast with an encyclopedic memory and a particular recall of true-crime shows on Investigation Discovery. “I’ve seen almost all of them now,” she says, “so I’ve moved to the Food Network.”

The three had been feverishly exchanging Facebook messages—with one another and with a handful of other volunteers on Lavender’s case—but none had met in person until we convened in a parking lot outside Austin. Kevin and Lori both live near the city; Missy had driven up the night before from San Antonio. As they got out of their cars, they did the will-we-shake-hands-or-will-we-hug dance of strangers who were not quite strangers. They opted for hugs. “It’s so weird,” Missy said. “We stay up all night on our laptops and everything. My husband’s like, ‘Who are you talking to?’” She laughed. So this is what it’s like to meet the people you stay up late discussing murders with.

Over the past six weeks, the volunteers had traced the origins of the young woman they believed to be Lavender Doe back more than a century, all the way to Europe. They had traced the outlines of her life, too, by digging through public records and MySpace profiles. They had done all that from living rooms and cafés—and now they were going to Longview to retrace the final steps of this woman they had come to know so strangely and so intimately.

From Austin to Longview is 250 miles of flatness. Missy drove while Lori navigated from shotgun, calling out Texas trivia about the small towns that whizzed by: Palestine, where debris from the Columbia space shuttle fell; Mexia, the hometown of Anna Nicole Smith. Kevin and I settled in the back. He had been sending me email dispatches about the case, but now he told the whole story from beginning to end.

He first became obsessed with Lavender Doe’s case in 2017. Back then, he was one of those people watching Investigation Discovery and trying to solve cold cases on his own. He had become especially preoccupied with the separate disappearances of two women not far from where he lived. It was when Kevin tried matching their cases to unclaimed bodies in Texas that he came across the dead woman near Longview known as Lavender Doe. He soon found the Websleuths thread too—the one that gave Lavender her name—and saw the 30-plus pages of speculation about her teeth and her clothes and the circumstances of her death. On Reddit in 2015, a woman began making annual posts about the “Girl with the Perfect Smile” and meticulously crossing off missing persons that had been ruled out. Her perfect teeth made the woman wonder if someone in Lavender’s family was a dentist. Her annual posts never had much new to report, but they kept the case alive in the public imagination.

The teeth were what made Kevin take another look at Lavender Doe’s case, too. Aside from her complete lack of cavities and fillings, Lavender still had two baby teeth—unusual for her age. One of the missing Texas girls had distinctive teeth, too. Kevin posted his theory that the missing girl was Lavender on Reddit. He also brought it to the lieutenant who had inherited her case at the Gregg County Sheriff’s Office, a man named, improbably, Eddie Hope. Hope was used to armchair sleuths sending in long-shot tips, and the missing girl had already been ruled out as Lavender. But he was grateful anyone cared. So little was going on in the official investigation, and the case haunted him. “I’ve probably got five more years before I retire,” he told me. “It will consume you.”

Kevin couldn’t let the cold cases go either. In his free time, he amassed court documents, filed public-records requests, and even interviewed the friends and family of missing girls. (Some were happy to hear from a stranger who cared, others less so. One mother abruptly blocked him on Facebook.) Since leaving his programming job two years before, Kevin had been selling T-shirts on Amazon, a task that paid the bills but scratched no particular existential itch. He decided a career change was in order and started taking classes to become a PI. He’d had a lifelong interest in genealogy, so when his PI program required an externship, it seemed only natural that he bring Lavender’s case to the DNA Doe Project.

The DNA Doe Project’s volunteers use genetic genealogy to solve cold cases. Margaret Press, an amateur genealogist and crime novelist, came up with the idea while reading a Sue Grafton mystery, and she recruited Colleen Fitzpatrick, a forensic genealogist who had previously worked with police. They co-founded the DNA Doe Project in 2017 to persuade law enforcement to test DNA samples from unidentified bodies, using technology that mimicked popular 23andMe and AncestryDNA tests, which is far more powerful than what forensics labs have had access to.

Law-enforcement DNA databases traditionally look at just 13 to 20 markers in the genome, which can be enough to match siblings or parents and children. In contrast, 23andMe and AncestryDNA look at different types of markers and test for 600,000 to 700,000 of them, which can reveal third and fourth and even more distant cousins who share less than 1 percent of their DNA. With these mere hints of a connection, genealogists can cross-reference census records, obituaries that list surviving family members, Facebook profiles, and other public documents to build out giant family trees.

As Missy drove, she told me that she was adopted and she had found her own birth father this way. That hooked her on genealogy, and she began spending 12 to 16 hours a day helping other adoptees find their birth parents. One of them ended up distantly connected to another DNA Doe Project case linked to West Virginia, which piqued Missy’s interest and obsession. She applied to join as a volunteer genealogist in early 2018—first to work on the West Virginia case, then two other cases, and eventually Lavender Doe, after the nonprofit officially took it at Kevin’s prompting. In August, DNA Doe successfully crowdfunded $1,400 to reanalyze Lavender’s DNA to get those 600,000 markers. Among those who pitched in were the amateur sleuths on Reddit, who had followed year after year the posts about Lavender Doe.

At the same time, the local sheriff’s office had a major and unrelated breakthrough in the case. Back when she was found, according to Hope, the semen inside Lavender Doe had matched—via old-school forensic methods—a man by the name of Joseph Wayne Burnette. He had admitted to picking up a female in the area for sex but admitted to nothing more.

In the summer of 2018, however, a woman living with Burnette disappeared, too. Hope and two of his men found her body, her purple fingernails sticking out of the leaves on the ground. Questioned again, Hope says, Burnette became talkative. Yes, he confessed, he had killed her, and he had killed Lavender Doe, too. But he maintained he had not known Lavender. She was a stranger, unlucky enough to have crossed his violent path in a Walmart parking lot in Texas. (Burnette pleaded not guilty to the two murders. His attorney says they are preparing for a trial in January and declined to comment further.)

Ultimately, this news failed to shake loose any new clues to her name. The murder indictment filed in August 2018 still listed the victim’s name only as Lavender Doe. The mystery of who she really was only deepened. Girls like her—girls who are blond with perfect teeth—don’t usually disappear without someone noticing.

The highway to Longview passes through a swath of Texas known as the Czech Belt, named for the immigrants who brought polka, folk dancing, and perhaps most important, yeasty pastries called kolaches. Lori made sure we stopped to get some for breakfast, a deliberate gesture, I later realized, in honor of Lavender Doe, whose Czech ancestry was one of the first things the volunteers figured out.

When they got Lavender’s DNA back from the lab in October, they uploaded it to a genealogy database called GEDmatch, the same one that investigators had used to find the Golden State Killer. Lavender immediately had thousands of matches, most of them too distant to be useful. But among the closest were what appeared to be a second cousin once removed and a smattering of third and fourth cousins. (Many months later, in May, GEDmatch would change its terms of service to limit which profiles investigators working with law enforcement could match. This has affected current cases, but did not affect Lavender Doe’s.)

The volunteers began building out family trees for the closer matches, trying to see how they connected in order to narrow down Lavender’s identity. They kept finding Czech ancestry. One volunteer even tracked down baptism records in the original Czech, in order to connect two of Lavender’s long-ago ancestors. A descendant of those same ancestors, a woman then in her late 50s, was still living in east Texas—just 30 miles from where Lavender was found dead.

Kevin alerted Hope. The answer suddenly seemed very close.

When Hope drove out to find the woman, she was hesitant. She did not know of a missing person in her own family—and it was hard to imagine that someone could not know of a missing person in their own family. “It still seems like a lot to be just a coincidence but stranger things have happened,” Kevin wrote to me after Hope’s visit. The woman did warm up to the DNA Doe Project once she fully understood the unusual situation that had brought law enforcement to her door, and she eventually let the volunteers compare her DNA directly with Lavender Doe’s.

The genetic connection was so strong as to be unmistakable: They shared enough DNA to be first cousins once removed. Lavender Doe was probably a child of the woman’s cousin—a cousin she did not know even existed.

Genealogy research is a task of startling intimacy at a great distance. When genetic genealogists started using DNA to build family trees in the 2000s, they invariably stumbled into family secrets: affairs, previous marriages, children secretly placed for adoption, sperm donations kept hush. The volunteers investigating Lavender Doe’s identity had been working with the remove of internet sleuths. But now they had made contact with her family—albeit family that did not know her—and they had to rummage through that family’s secrets to find her.

They went looking for unknown cousins of the woman. One of her uncles, it turned out, had a daughter named Robin, from a previous marriage that the east-Texas woman also did not know about. Kevin found a death certificate in Indiana for Robin, who had died of an illness at age 50 in September 2006—just a month before Lavender Doe was found dead.

Could Robin have been Lavender Doe’s mother, and could this explain why Lavender had never been reported missing? Robin’s death certificate, along with what the volunteers could piece together from police records and newspapers, told a sad but not unfamiliar story. “We saw that she was not stable, had a lot of alcohol-related arrests, had a bunch of different husbands,” Kevin recounted to me on the drive to Longview. The mood in the car shifted ever so slightly when he said this. We had been enjoying the road trip and the kolaches, and now we were reminded that, at the end, there was always going to be a girl, dead and abandoned.

The volunteers kept researching Robin, and the leads piled up quickly. DNA had helped them zero in on this branch of the family tree, but the rest of the work was digging through newspapers, legal records, social media, and people-finder databases that collect an astonishing amount of personal information. The volunteers found marriage records for two husbands and surmised that she had a third based on a last name, Dodd, occasionally appearing in newspaper articles about her arrests. Kevin put that version of her name, “Robin Wilma Dodd,” in Google and came across a free preview for a people-finder site that listed her as living with a man by the name of Johnny Dodd. The connection was tenuous but it would be enough: Kevin searched the man’s name and found a daughter who seemed to be Lavender’s age.

It was the next search that gave Kevin chills. He put the daughter’s name into Delvepoint, a database for private investigators, and it revealed that her Social Security number was no longer active. In fact, she seemed to have completely dropped off the map right in 2006—the same year Lavender Doe was found dead.

Kevin searched the name in more databases. Dodd had children from another marriage in Jacksonville, Florida, and those children had children. He found a MySpace page that belonged to a nephew of the girl he thought could be Lavender Doe and then very quickly he found another profile that could have belonged to Lavender herself. He pulled it up for me in the car, a time capsule from the early 2000s. There she was hugging a dog. There she was posing in a white miniskirt, her hair long and strawberry blond.

The last place Lavender Doe was probably seen alive was a Walmart parking lot in Longview. When we arrived in town, Hope led us there to retrace her steps. He relayed what Burnette had said in his confession: “She came up to him selling magazines. He didn’t want ’em. Then she tried to try to sell him some lingerie out of a magazine. He didn’t want that. She asked if she could get in the truck with him. He let her in.” She agreed to have sex, according to Burnette, but stole money from him. That’s why he allegedly strangled her but left $40 in her pocket. That was money she had earned, he said.

From there, according to Hope, Burnette brought her body to a patch of trees where he burned her. The road that he would have taken no longer exists today, so Hope had to lead us through someone’s yard to a wooded area. The oaks and maples had all dropped their leaves for the fall, covering the ground in a thick, rustling blanket. It would not have been so different when her alleged killer carried her body here, 12 years before our visit.

“This is where he burned her.” Hope stopped, just short of a shallow creek that had run dry, and we all stopped too, trying to reconcile the image in our heads with the image before our eyes. “I just expected it to be a little more dense,” Missy said. A house was visible through the bare trees. What about the smoke?, she asked. How could he have thought no one would notice? “Those houses were there,” Hope confirmed. “They’re just right there,” Missy repeated. The girl had been surrounded by people but so alone.

After the autopsy, Gregg County interred her in a small cemetery in Longview on December 23, 2006. Her tiny headstone listed that date, but no birth date. The only name was Jane Doe. By the time we got to the cemetery, it was late afternoon, and the sun was on the wane. The wind that had been bearable under sunlight was now slicing through our thin jackets. But we lingered, no one wanting to be the first to turn away. Missy had brought flowers—mums the color of lavender—to set on her grave.

Hope left after about an hour, but the volunteers stayed by Lavender’s grave. Lori had the idea to do a Facebook Live stream for the DNA Doe volunteers who could not make it on the road trip. She held up her phone, and we huddled behind her. “Not sure if everyone is paying attention in the group, but we are at the cemetery”—and here her voice goes from singsong to hushed and somber—“where our Doe was interred.” She turned the camera toward each of us: “Say hello.” And we each said hello, unsure of whether to smile as one usually does in a greeting on Facebook Live, unsure of the proper protocol for visiting the grave of a stranger whose life you have spent weeks digging through.

Another volunteer who worked on the Lavender Doe case, but who could not come on the road trip, watched the Facebook Live stream and left a comment that so stuck with Lori, she quoted it back to me months later. The volunteer had observed, simply, that we were the first people in all these years to ever stand at the grave and to know her real name.

Dana Lynn Dodd. That was her name. She was barely 21 when she was killed, in the fall of 2006.

In May, after DNA had proved the volunteers were right, I went to Jacksonville, Florida, to meet Dana’s family and high-school best friend. Following Hope’s call to Dana’s family, the DNA Doe Project had mailed her half sister Amanda Gadd an AncestryDNA kit. The results came back a couple months later and confirmed that Dana was the girl found dead near Longview, Texas; the girl on that MySpace page; the girl with perfect teeth.

The news provoked an odd mix of elation and sadness for the volunteers. A puzzle, solved! But also a family, now in mourning. “You want to have a party, jumping up and down,” Missy told me. “And, oh wait, wait, we can’t have that kind of attitude.” She struggled to suddenly let go of the case that had consumed her every waking hour for weeks. Missy kept wondering about Dana’s family—about what happened that she would die nearly 900 miles away from home, about what her family thought during all those years, about what they were thinking now.

I wondered about all this, too, and I wondered how much we deserved to know. It had struck me, as I followed the volunteers over the course of their investigation, that their work paralleled the work of journalism. It had unsettled me for the same reason that the work of journalism sometimes unsettles me. Dana’s family had not asked for strangers to dig through their family history, and they had not asked for the hot glare of press attention. Her case had been plucked from obscurity among thousands of unidentified bodies every year—elevated by true-crime obsessives, until it caught the attention of genealogists and then me. When the power of genealogy to solve crimes became apparent last year, my editor’s assignment was, quite literally, to find a murder.

By the time I left for Florida, I knew enough about Dana’s family to know she was certainly not the daughter of a dentist. Her perfect teeth were probably a lucky anomaly. Her mother had died rather young and far away from her. According to police records, her father was homeless. He had been arrested multiple times for public drinking and disorderly intoxication. Neither parent raised Dana, Amanda told me at her kitchen table in Jacksonville. Amanda is nine years older, and the half sisters have the same father. They once shared the same strawberry-blond hair too, but Amanda’s had faded to a paler blonde now and Dana, well, she had been dead for more than 12 years. They were not especially close when Dana disappeared, but the long silence told Amanda something was wrong.

Dana, her half sister said, had spent her young life bouncing from household to household. Her mother left when she was a baby; her father not long after. She lived with a stepmother in Arizona until age 14, when that stepmother decided to send her to family in Florida. Before then Amanda had met Dana only twice—years earlier—but at 23 she was a young mother herself. She took Dana in. As she remembers it, her younger half sister arrived with a single backpack containing all her possessions in the world. Amanda got her into counseling, and there was stability for a while, she says, but also teenage rebellion. Dana bristled against curfew and chores. She went to live with her older half brother, who was Amanda’s full brother. She didn’t stay long there either.

There were weed and pills, a bad boyfriend, trouble with the police for underage smoking and fighting. Dana dropped out of high school. She moved in with her best friend, and then she skipped town to join a traveling magazine-sales crew, the type of group that often lures workers in with the promise of travel and then traps them with violence and drugs. No one has tracked down the exact crew Dana joined, but other workers have spoken of beatings and denial of food for failing to meet sales quotas. That’s likely how Dana had come to Texas: Burnette told the police she’d tried to sell him magazines first and then lingerie. When he declined both, she asked to get in his car.

The idea that Dana would climb into a car with a stranger, that she would have been so desperate as to do that before asking her family for help, troubled Amanda. “I think, after all the years, she thought she had nobody,” Amanda said. “I think that’s why she didn’t reach out to us.” She said their brother felt he had let Dana down. I asked if she felt that way too.

“I do,” she told me. “I did my best. I feel like I didn’t do enough.”

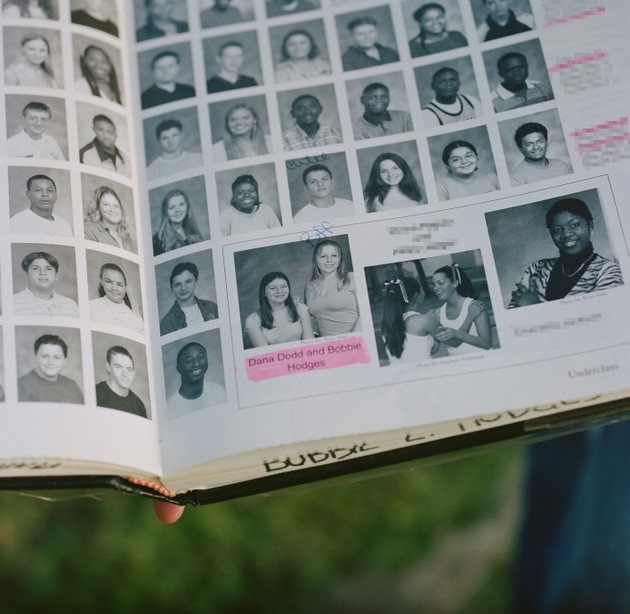

“I almost wish I never told her to leave,” says Bobbie Lynn Hodges, Dana’s high-school best friend. The two girls first met in 10th-grade health class, and they had bonded quickly over their troubled family backgrounds. When I saw her in Jacksonville, Bobbie pulled out her old high-school yearbook—in which Dana had written an entire page—and a photograph of the two girls in matching T-shirts that read Frick and Frack. She still had the T-shirt to show me, too. She had stopped wearing it when the letters started to fade, but she kept it in her pajama drawer. “I loved her to death,” Bobbie told me. She’d hung on to the T-shirt, all the years after her friend had left.

According to Bobbie, this is how it happened: They were living in a duplex together when Bobbie found out she was pregnant, after partying and getting high on her 18th birthday. Dana stood right next to her when Bobbie peed on the stick the next morning. This moment of intimacy ultimately became the rupture in their relationship. Bobbie wanted to have the baby and to get clean. Dana didn’t. Bobbie says her friend began injecting heroin, and she stole a PlayStation from their apartment. That’s when Bobbie kicked her friend out. “When she left, she said, ‘You're my last person. Nobody else will help me.’” Dana joined the magazine crew soon after.

Those last words clearly weighed on Bobbie, heavier now that she had learned of her best friend’s death. “If I wouldn’t have kicked her out, like, where would we be now?” she asked. She answered her own question. “I’d be right there with her … I would probably be dead too.” She had spent the past 12 years struggling with drugs herself.

In the intervening years, Dana’s family had searched online and made phone calls to follow up on rumors they heard about her fate. They wondered, in the best days, if she had started a new life. Maybe she had a husband now, a career, and kids. Her nephew—the one whose old MySpace page Kevin found—told me he had messaged countless “Dana Dodds” on MySpace. When Facebook came along, he looked for “Dana Dodds” there, too. They were never her, of course. She had been dead this whole time.

In September, for what would have been Dana’s 34th birthday, Amanda and a few other members of the family traveled to Texas to visit her grave. They brought flowers, a birthday balloon for all the birthdays they had missed, and a new headstone—this one with her name. “She was given that name when she came into the world,” Amanda said. And she was given that name again in death. It only took 13 years.

As the DNA Doe Project has solved more cases, the volunteers have recognized they have entered into something far more complicated than reuniting grateful families. Some of the Does had no one still alive to miss them at all. Many had mental illnesses or drug addictions. Almost none had been reported missing.

“In my mind,” Missy says of her preconceptions, “it was the girl next door, with the white picket fence, the perfect household, and the two and a half kids. The mom and dad have great jobs, and the parents go to church on Sundays.” Instead, it was the reality of violent crime in America—where the poor and the marginalized disproportionately make up the victims. These are not the stories that make up the genre of true crime. They are the true story of crime.