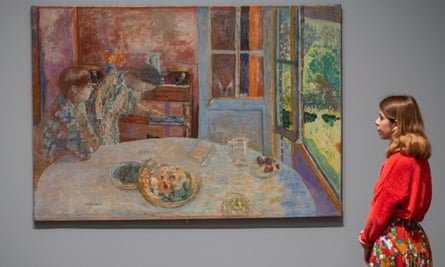

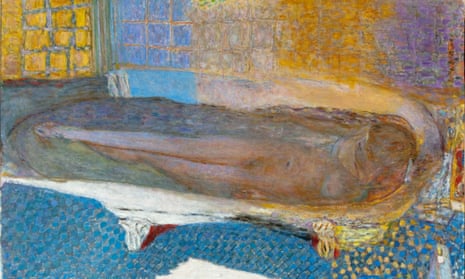

Pierre Bonnard in the bathroom mirror holding up his hand like a boxer, though really he is clutching a wet sponge. Bonnard on film, in a snatch of home movie, blinking incessantly behind his little round glasses. Bonnard in the kitchen (I’m sure the housekeeper would rather he went away) and out on the terrace. Bonnard hovering here and there; Bonnard beside the tub, as his wife takes yet another bath.

I am ambivalent about Bonnard. The things I admire and that interest me in his paintings are not perhaps the things he fully intended. Aspects of his work that others find charming or life-affirming I soon weary of. All that colour, all that fidgety brushwork. His figures are very hit-and-miss, sometimes crude and absurd; sometimes the distortions seem terrific, at other times horrible. I can’t bear the way one naked female leg is always warm, the other always cool, and why Bonnard teases the viewer with one female nipple always being in stark profile. He can be monumental, he can be scrappy. Faces in the crowd are often monstrous or ill-formed. Bonnard did not have a facile talent: he had to work at things. There is a great deal of niggling about, and piling paint on. I think he found landscape easier, a relief from the tensions of the human subject.

At the artist’s last retrospective, the critic David Sylvester told me that if I didn’t get Bonnard, I didn’t get painting. I suppose he might have been right, and his remark may have had something to do with why I am no longer a painter, but I doubt it. Bonnard kept on painting through the long procession of days and seasons and years and wars and time without suspense.

I have an image of him moping and lurking about the place, going in and out of the studio to add a touch here and another touch there between breakfast and lunch. Bonnard’s paintings are full of complications, equivocations and repeated attempts at resolution. His best paintings do seem to accrue a kind of incremental silence. I hear the sound of dripping taps, a metronome of ennui. Just maybe, this is exactly what Bonnard is trying to capture.

Plenty of people really love Bonnard. I like that painting where two women are bending to fuss over the dog, but all you can see of the creature is its nose and snout poking up over the cloth on the far side of the kitchen table. Judging by other dogs he painted, this was a good way of not having to deal with the whole canine. But Bonnard was good at uncomfortable human proximity, and also at cropping figures, though I think he could have made more of this, and added to what psychological drama (the unseen, the glimpsed, the idea that the viewer is a kind of furtive interloper) that his pictures do contain.

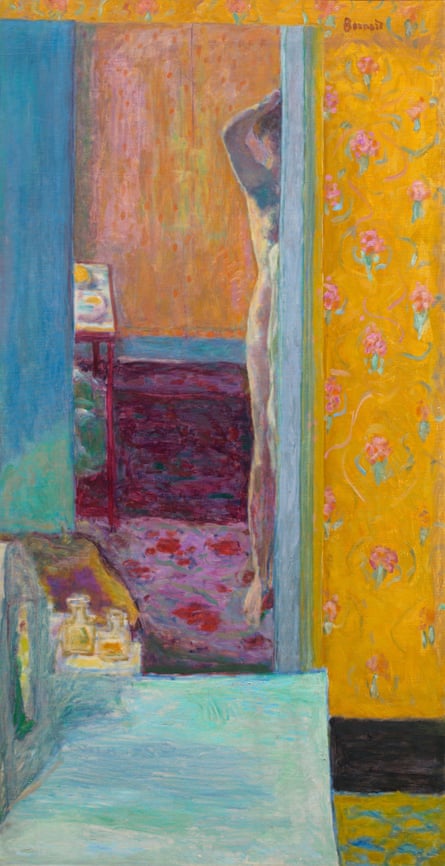

A 1935 Nude in An Interior stands in a doorway, raising her hand to her head. We glimpse only a vertical sliver of her, one foot, one knee, one hip, one breast, one arm and less than half her head. You almost expect her to slam the door as we pass by. I am beginning to feel like a house guest who has only just got the hint that they’ve outstayed their welcome.

In a much earlier work from 1900, a naked man and woman in a frowzy bedroom are separated by a folded screen that divides the image down the centre, as though by a cinematic split screen. She is on one side, absorbed by the two cats on the bed, he on the other, towelling himself down, and partly cropped by the edge of the canvas. You wonder what he is thinking. You can imagine all kinds of stories. Is it me, or is it somehow very claustrophobic in here?

Mostly, Bonnard painted his companion since 1893, Marthe de Méligny, though sometimes his model and, later, lover Renée Monchaty. In 1921, Bonnard went to Rome with Monchaty. It seems he was as indecisive in love as he was in painting. In 1925, Bonnard and de Méligny finally married, and three weeks later, Monchaty killed herself.

I like the way cups and bowls and jugs are so often tilted towards us on the picture plane to reveal their insides and what they contain – as if to say: “Nothing to hide here” – showing us that there are no secrets. But there always are secrets in any domestic scene, things kept from us, things kept from each other. These are not Walter Sickert’s Camden Town Murder paintings, or scenes from the everyday lives of the Bovary household, or of Patricia Highsmith’s Mr and Mrs Ripley, at home among the soft furnishings with the body bleeding on the wine cellar floor. If there had been, Bonnard would have painted the stain in at least three types of crimson, as he tried to capture the memory.

Blossom bursts, the foliage is variegated, light strikes the kitchen door, the figs in the bowl are ripe, the bathroom is quiet, the views are always marvellous, and Madame continues with her hydrotherapy. No wonder Bonnard looks shifty in his self-portraits in the bathroom mirror. I feel uneasy, too, about the man in the mirror. The exhibition takes us from 1900 to Bonnard’s death in 1947, and it feels as if we have been here all that time. Tate wants us to slow down to really look, absorbing the colour, the light, the atmosphere. Everything was absolutely lovely. I couldn’t wait to get away.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion