Pierre Bonnard in deep winter: what could be more promising? All those sultry interiors and ripening fruit, languid figures half-glimpsed in the circulating heat, windows thrown open to sun-drenched gardens, visions of bougainvillea under burning cobalt skies – the south of France in perpetual summer. His paintings are high season for the eye. A January day and Bonnard gives us exactly what we expect, and yet these joys are peculiarly qualified.

This is the first full-dress showing in Britain for 20 years, with more than a hundred paintings, scores of drawings and enough photographs of Bonnard (1867-1947) and his wife, Marthe, in the nude to adjust the conventional image of an anxious lawyer with an uptight handkerchief and toothbrush moustache. It is an even-handed presentation, almost to a fault, with too many early Paris streetscapes and late-life Cannes landscapes (Bonnard turns curiously conventional outdoors). But it has everything else one might hope for – the bather paintings, in which Marthe seems almost to dissolve in luminous colour; the elusive rooms where women hover in the margins; dozens of effulgent still lifes; above all the tremendous and shocking self-portraits.

Marthe is there almost from the start, as she was in life. Bonnard met her in Paris in 1893, when both were in their 20s. Small, cat-like in her movements and pronounced self-containment, Marthe lived with him for more than 50 years. Bonnard would ask her to walk about for preliminary drawings, and there is some sense of recollected motion in the standing nudes where he suddenly seems to come across her in front of the mirror, with a towel, or before a window that edges her body with something more like opaque liquid than sunshine. She is never defined so much as mystified by his light.

Marthe it is (though her form is always more recognisable than her face) at the far end of The Table, where Bonnard’s singing yellow gilds the dinner plates, steals inside brass bowls, ignites the oranges and apricots. She turns away from the main spectacle, which is nothing less than the tablecloth itself – a spreading sea of whiteness upon which everything else is borne. Bonnard struggled, he said, to understand the magical secrets of the colour white; even in his 80s, he believed he was just beginning to paint.

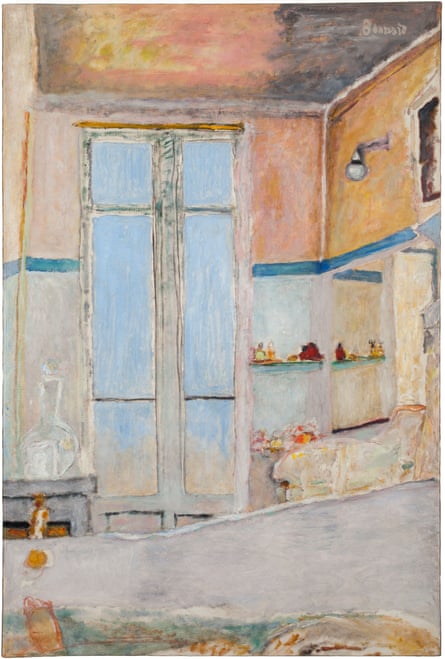

The beauty of his saturated colours – soft mauves, hot blues, the staggering range of yellows, reds and whites – always seems at odds with the diffident brushwork. Look close and you see muzzy washes, gentle dabs, tremulous stipplings and strokes. He becomes preoccupied with one area – the shadow beneath a chair, bars of sun through a window – and the absorption shows itself in the pensive, unhurried marks of his brush on pieces of canvas that were generally tacked, unstretched, to the wall.

Bonnard worked everywhere in the house; Marthe was always at home. Her presence is there, you feel, even when her figure is not. There were other lovers, particularly when Bonnard was in his late 40s and fell in love with a young model; she killed herself when he later changed his mind and returned to Marthe. Bonnard is said to have painted darker night scenes around this time, but the crisis is nowhere visible at Tate Modern; and despite the curators’ inclusion of two hopeless battle landscapes, neither is there any sense of the horrors of war.

What were the couple to each other? That is one of the abiding enigmas of his art, and this show. The same woman keeps appearing, her face averted, in and out of the bath, on the margins, repeatedly from behind. Her legs rise vertically up the canvas, lying in the tub; her head bends low over some unseen work. Her body is boneless, tubular, like that of a cloth mannequin. She never changes; she never ages. It is as if she never speaks. Bonnard’s friends described her as practically silent.

And there he is again, and again, watching her across the dinner table, looking up at her as she stands pinning her hair, or down at her in the pale tomb of the bath. Marthe spent hours there every day, trying to stave off some physical or psychological complaint that has never quite been established. Perhaps Bonnard turned to the venerable theme of bathers because of it; perhaps they were both equally immersed, as it were, in the concatenation of light on water, ceramic tiles and glass panes, by the mingling of ripples, colours and refractions. In at least one work, painted two years before her death in 1940, Marthe is so deeply absorbed within the silver-blue scene that her body scarcely registers at all.

Bonnard said he wanted his art to convey the experience of someone just entering a room, trying to take in the full optical plenitude. Perhaps it is true that our eyes sometimes overlook the presence of others in the first second or two, but Marthe’s fugitive person (or is it personality?) – sometimes just an ankle, an arm, or a sliver of profile – is something quite else. She is contained within a scene like the water inside the bath, the fruit within the peel, the room inside the house: each phenomenon simply there and coexistent with the others. Bonnard paints a continuum.

Flowers float free of the wallpaper to become entwined with vases, drapes, the very atmosphere of a room. Light drifts, people are withdrawn, patches of colour melt like snow. Some of Bonnard’s paintings defy legibility altogether, at first. What would we do without all those marked verticals – the edges of doors, windows, wardrobes, screens – that seem to structure the image; except that they too may prove confusing. It is sometimes said that these uprights refer to the business of painting on rectilinear 2D canvases; but my sense is that he is never so programmatic. The pleasure of looking at a great Bonnard has at least something to do with the struggle of its making, of trying to get the impression of a room (or even just the memory of that impression) into the picture whole.

Bonnard was prolific – and uneven. Too many mediocrities are jumbled among the masterpieces at Tate Modern. It would have been a revelation to see the bath scenes grouped, instead of scattered; to see the self-portraits isolated from the flaccid landscapes around them. Bonnard can be twee – pop-up cats – and it seems only honest to concede that Marthe sometimes looks like a doll. What he felt about their marriage – shared happiness, mutual bondage – is not vouchsafed, except in the way that he paints; and possibly in Bonnard’s self-portraits.

These paintings breach the supposed serenity of his art. The artist appears lonely, trapped in the mirror – blood-red and raw as if flayed, or raising puny fists as if to fight his poor self. There are the fascinating bathroom tiles, and a shelf of gleaming objects to praise. But behind them, he is a ghost in glasses, or a Noh tragedian with black eyes in a grief-stricken mask. In the most devastating of all the late self-portraits, Bonnard has become a pale, bald spaceman of indeterminate age – baffling in his own eyes, a stranger even to himself.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion