It is the summer of 2019 and Colson Whitehead is sitting in midtown Manhattan thinking back to the birth of his new novel, The Nickel Boys. “It was 2014,” he recalls, “and it was a rough summer in terms of race and police brutality. Michael Brown was shot by a white cop in Ferguson, Missouri. Eric Garner, who was selling bootleg cigarettes in Staten Island, was choked to death by a cop. And no one was being held accountable. No one was being disciplined or going to jail. And then I came across Dozier School.” The Arthur G Dozier school, more formally known as the Florida School for Boys, existed from 1900 to 2011 as a reform institution for youngsters deemed juvenile delinquents. Locally, and for much of its history, it was notorious for the beatings and torture meted out to students by whip-wielding staff. Many dozens died in mysterious circumstances and were buried in unmarked graves. Until the second half of the 60s, black and white boys were held in separate quarters. It took the efforts of former internees, known as the White House Boys, and the campaigning journalism of the Tampa Bay Times’s Ben Montgomery for this dark history to come to light.

“I was shocked I’d never heard about it – and shocked it wasn’t getting more attention,” Whitehead says. “And then it dawned upon me: Michael Brown and Eric Garner are just a couple of examples of the many terrible incidents that are happening around us that we don’t see. Dozier is one reform school; there are more. Then there’s the tragic fact that no one cared. For a couple of decades, kids were coming forward. And nobody cared. Not even now: they were digging up bodies but it was just a one-day news story.”

In the 20 years since the publication of his first novel, The Intuitionist (1999), Whitehead has been a protean, rather slippery writer. His fictions are mordantly anthropological, often play with genres (crime, satire and, in the case of 2011’s Zone One, zombie horror), while his non-fiction books have dealt with post-9/11 Manhattan (The Colossus of New York) and the World Series of Poker (2014’s The Noble Hustle).

Early on he was hailed by John Updike and won a MacArthur “Genius” fellowship in 2002, but it was the publication of The Underground Railroad in 2016 that really made his name. A hybrid of historical and speculative fiction, it imagines the existence of a transport system that 19th-century black Americans could use to escape slavery. The novel was praised by Barack Obama and Oprah Winfrey, sold more than a million copies, and won him both a National Book award and a Pulitzer prize. It is being adapted for Amazon by Barry Jenkins, the Oscar-winning director of Moonlight.

Whitehead, who was born in 1969, wasn’t always drawn to literary fiction. As a teenager he preferred video games and “hanging around the house reading Marvel comics and Stephen King novels, and watching John Carpenter movies. I did think, as a profession, it would be cool to make up stories about robots and apocalyptic landscapes. And The Twilight Zone seems like a cool show: maybe I could get a job on The Twilight Zone. I wanted to write horror novels, novels about werewolves, and Salem’s Lot-type towns taken over by vampires.”

The Nickel Boys, like many novels about black American history, is a horror story, grotesque and gothic. Set in the 60s, it follows Elwood Curtis – young and idealistic – as he works diligently under the watch of his strict grandmother to win admission to a local college, only to have that future wrenched away from him because of an innocent mistake. He’s whisked away to the “Nickel Academy” where he does his best to resist being brutalised and hatches an escape plan with his cynical pal, Turner.

“You can compare this case to what happened in Catholic orphanages or in aboriginal camps,” Whitehead observes. “Any place where you have corrupt, malevolent authority figures who can exert their will on the innocent and powerless, then you’re going to have this: the school as a plantation.” The ease with which these metaphors connect slavery to the present day is, he believes, very telling. “In terms of institutional racism and segregation and white law enforcement attitude towards black people: you can say something from 1850 is true for now.

“I wrote about slave patrollers in The Underground Railroad, it was their job to stop any black person, free or slave, to check their papers. That’s the same as ‘stop and frisk’ now. ‘Show me your ID! What are you doing here?’ It’s policing black mobility.”

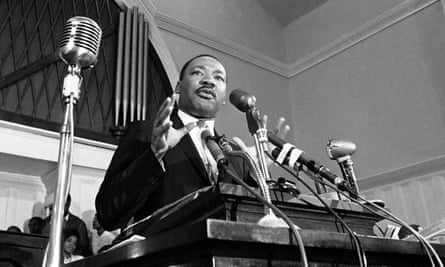

In The Nickel Boys, Elwood’s dreams are partly inspired by Martin Luther King, an LP of whose speeches he receives as a Christmas present. “I wanted Elwood to be motivated by the spirit of the civil rights movement. Hearing King speak, you’re struck by what an impossible figure he is. Maybe we created him out of necessity? How can someone so eloquent and wise and visionary survive as long as he did in this sort of crappy country? Of course they had to kill him. All the civil rights protesters: they knew they would be faced by hoses and baseball bats and crowbars. And yet they got up and marched anyway? It’s impossible – and also true.”

Perhaps it was his interest in comics (shared by authors such as Jonathan Lethem and Junot Díaz), his energetic prose (notoriously criticised by James Wood), or the fact that he lived in Brooklyn (like almost every other New York writer), but Whitehead has regularly been said to be in sync with his times. In a review of his novel Sag Harbor (2009), about Smiths-listening black kids living the good life one long summer in Long Island, the critic Touré bracketed the writer as part of a cadre of “postblack” figures – others included Kanye West, Questlove and Zadie Smith – who “can do blackness their way without fear of being branded pseudo or inconegro”.

“I don’t think of labels in that way,” Whitehead argues. “My first book was about elevator inspectors. It’s about race and cities … but using elevators. I’ve always sort of tried to find a weird angle on something. When I wrote a zombie novel I didn’t ask myself: should I be writing a zombie novel? I like zombies so I wrote a book about them. When I was writing The Underground Railroad I didn’t think it was a historical fiction; I thought it was a novel that had some fantastic elements.

“Having said that, right before The Underground Railroad I was planning to write a novel about new media culture, circa 2011; about the collapsing journalism model and the internet. Then I thought: maybe there’s a really angry 27-year-old who can probably do it better than me? I’m a paunchy fortysomething with a mortgage and kids.” He laughs. “I think the kind of fire I had to take on contemporary society is a bit diminished now.”

The Underground Railroad, about the pursuit of emancipation, was written in what Whitehead calls “the happier Obama days”. The Nickel Boys he describes as his “Trumpian novel”. What does he mean? “The shifting of gears from Obama to Trump was pretty sudden. I’m a big news junkie and when I started writing it in the spring of 2017 I was horrified – the Muslim [travel] ban, an FBI chief being fired, hate crimes on the rise. I didn’t know what to make of it. I think there’s a part of me that is hopeful that the human race – America – is moving towards a better version of ...” He pauses. “Then of course there’s the reality which is that we have kids being shot by racist cops. We have kids in concentration camps on the border.” How can you be hopeful? “Exactly!” he laughs, before shrugging, “I have kids. I have to be.”

Whitehead was included in Paul Beatty’s Hokum: An Anthology of African-American Humor, published in 2006. Laughter and sadness cohabit in much of his work. “I think the world is tragic and the world is funny,” he declares. “I grew up watching George Carlin and Richard Pryor with my parents at a very young age. They both veer between incredibly sad and totally slapstick. They’re mugging – but also reaching for some elemental truth about what it is to be a person in a body on this planet.”

He cites Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), particularly a scene set at a boxing venue where a naked blonde woman with a tattoo of the American flag below her stomach provokes drooling chaos from the punters, as a perfect conjunction of the “funny and terrible. In Beckett and García Márquez too: there’s a knowing wink at humanity’s foibles. The Noble Hustle and Sag Harbor are more broad, but definitely in The Nickel Boys there’s a gallows humour with the young boys trying to get whatever edge they can on their supervisors.”

As a child in Manhattan, Whitehead was called Arch. He later switched to Chipp, one of his middle names, and then to another, Colson. These name-changes are matched by a fondness for code and genre-switching; the roots of which perhaps lie in his adolescence. “My sister’s a nurse now, but she was really into music. I’d walk by her room and she’d be playing Gang of Four and Grandmaster Flash. This cross-pollination between genres – reggae, dub, punk and hip-hop – all came together in a great moment from 1978 to 1984. At the Peppermint Lounge they’d have an electronic hip-hop floor and downstairs they’d have the Cramps – and then on another floor would be Madonna. And you’d just go up and down this five-storey club and find these different subcultures all hanging out with each other.

“When I heard Planet Rock by Afrika Bambaataa I recognised the sample from Trans-Europe Express by Kraftwerk. Sampling and borrowing from different genres always seemed very normal. And so, you know, you can like dub music and punk. And also listen to T Rex. And also: you can write a zombie novel and you can write straight historical fiction and you can write a realistic novel and a fantastic novel.”

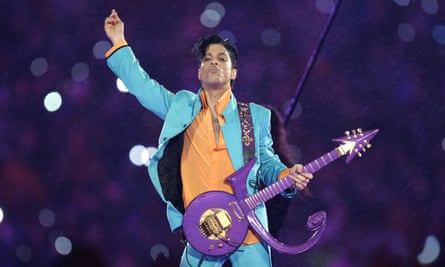

Whitehead has an abiding passion for the music of that period. He enthuses about the gothic dub of Bauhaus’s “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” (“That song always cracks me up. Where does that come from? It’s like an eight-minute song …”), and writes to a self-compiled playlist of over 2,000 tracks. He has a particular fondness for shapeshifters such as David Bowie and Prince. “Up to the mid-80s, Bowie is changing persona with each album: you exhaust something and then try something new the next time out. That seems a natural lesson which I took in. With Prince, he’s constantly saying ‘fuck you’ to those conventions about what you should be doing as an artist – or as a black artist. And hopefully I’m taking that lesson and using elevators to talk about race – or writing a book like The Colossus of New York that’s devoid of anything to do with race.”

Whitehead talks with affection about downtown New York in the 80s – “it was a great time to be young in the city; the drinking age was not yet 21” – but he’s particularly garrulous about the Village Voice, the countercultural weekly co-founded in 1955 by the English journalist John Wilcock, for which he wrote essays and television criticism in the 1990s. “Nowadays pop cultural criticism – the focus on identity and critiques of institutions – is everywhere,” he observes. “The Village Voice made that possible.”

He was part of a constellation of writers – among them Greg Tate, J Hoberman, Hilton Als, Manohla Dargis – all of them theory-savvy, blase about the distinctions between high and low culture, and as enjoyable to read for their prose as for their opinions. “Those writers had a multi-discipline expertise that was really inspiring. Everyone was broke at the same time. Everyone was about to find their voice. Everyone hung out and dated each other. That institutional tutelage was really important for me; I’m not sure how it works now if you’re working in your own home and working on some web thing and hoping to get noticed.”

The success of The Underground Railroad means Whitehead himself no longer has to worry about getting noticed. Earlier this month he appeared on the cover of Time magazine. It sported the words US publications reserve as the ultimate praise: “America’s storyteller”. His daughter, now 14, is less easily impressed. “I told her Railroad was a No 1 bestseller. She was like: ‘Er’. I said: Oprah picked it. ‘Er’. Then: I’m gonna do a BuzzFeed interview tomorrow. ‘BuzzFeed?!’ That sort of made it real for her.”

Equally memorable was the time he encountered Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth, the band whose records he worshipped as a teenager. “I introduced myself nervously – like: ‘Hi Thurston.’ And he said: ‘We love John Henry Days! We’re reading it on the tour bus. We’re underlining passages and reading parts aloud.’ It was mind-blowing!”

Whitehead no longer needs to spend part of each year teaching creative writing classes. Instead he travels to different countries to meet new publishers. He admits that “with Nickel Boys I was writing on trains and planes and hotel rooms just because if I didn’t it wouldn’t get done.” (He has been asked to go to Florida to talk about the Dozier boys but has so far refused. “I’m still angry and sad. In terms of an exhumation, it’s not my story; it’s their story. I don’t want to intrude upon that.”)

His publicity schedule means that his next book – a crime novel set in 60s Harlem that he’s a third of the way through writing – is currently on hold. Recently he flipped through his second novel (John Henry Days) and found himself thinking: “This is pretty long. This is pretty dense. I could probably never do this now.” He’s been studying novellas, among them Edith Wharton’s Ethan Frome, as shorter fiction becomes more appealing.

He would never begrudge his international commitments. If anything, they allow him to see his work in a new light. “I was surprised with how well The Underground Railroad travelled. In Poland people told me: ‘We connect abolitionism – hiding people, getting them to safety – to the Polish resistance against the Nazis.’ The power dynamic between slave masters and slaves is like that between royalty and peasants – and that’s global history, not just American history. But I don’t really think about the audience: my motivation to write a book about two black boys in the 1960s just comes from the fact that, historically, America doesn’t care about them.”

The Nickel Boys is published by Fleet (16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.