The question of the Irish border brought the Brexit talks to a halt on Monday when the DUP stymied an emerging deal. The unfolding drama this week was no surprise to anyone with even a cursory knowledge of the island of Ireland and the delicate balances that has kept Northern Ireland in an uneasy peace over the last 20 years.

The question of Ireland was always going to be one of the most difficult to resolve, and remains so. The agreement reached in Brussels is just a staging post, with many twists and turns ahead. That said, the joint statement is a significant achievement that meets the needs of the Irish government and the DUP for now.

The DUP will be content that it had London’s full attention and managed to muscle its way into the Brexit negotiations. The emphasis on the constitutional status of Northern Ireland as part of the UK, the principle of consent and the unfettered access of Northern Ireland to the UK market meets its demands. Ironically the DUP, a party that campaigned against the Good Friday agreement (GFA), has now consented to its insertion into an international treaty backed by the EU. By supporting Brexit, the DUP has put the Irish border back on the political agenda – something that may, in time, undermine their union.

The Irish government, seized of the Brexit issue from the beginning, has devoted all of its political and diplomatic resources to ensuring that Ireland was a core part of the EU27 agenda and that any agreement with the UK would protect the GFA. The issue is existential for Ireland, something that has not always been fully understood in London.

For Dublin, the agreement secures all of its key objectives for now. The UK commits to the protection of the GFA in all of its parts and crucially commits to the avoidance of a hard border, including any physical infrastructure. Moreover, all future arrangements must be compatible with this overarching commitment. Thus the principle of no hard border on the island of Ireland is a core commitment governing the UK-EU relations. It will be integral to the withdrawal agreement, which takes the form of an international treaty between the EU and UK.

The commitment to no hard border is one thing, but how is it to be kept? Here the agreement suggests that the UK’s first preference is to achieve this within the overall context of EU-UK relations and to offer bespoke solutions for the island of Ireland only if this proves impossible. If this is insufficient, the UK further commits to full alignment with the rules of the customs union and the single market. A commitment to full alignment is very strong as the EU interprets this as convergence with EU rules.

Significantly, it has been agreed that there will be a separate strand of work on Ireland in phase two of the talks. This ensures that Ireland will be central to all discussions until the end game and will not be overwhelmed by other issues.

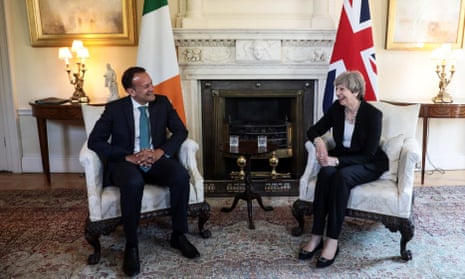

The feeling in Dublin will be one of quiet satisfaction but the government knows that far more difficult discussions lie ahead. The heart of the problem still lies in London. The prime minister, Theresa May, has got her cabinet to the end of the first phase by essentially meeting all EU requirements but without resolving the glaring divisions in her cabinet about the final destination.

When that discussion takes place as now it must, addressing the incompatibility of leaving the customs union and single market with no hard border in Ireland cannot be avoided. It could well be that the Irish question has already forced the UK towards a softer Brexit – or, if this proves too much to swallow for the hard Brexiteers, the consequence might be a political crisis in the early part of next year.

Regardless of what happens, London should understand that the Irish government, backed by a deep consensus in Irish society and supported by the unwavering solidarity of EU27, will hold them to the commitments made in this agreement and will not sign up to any future trade agreement that violates it.