Ahead of the London mayoral election of May 2012, I was invited to chair a hustings at St James’s Church in Piccadilly. The main attractions were Boris Johnson, seeking his second term, and his doughty detractor Ken Livingstone, alongside their good-natured warm-up acts of Jenny Jones for the Green party and Brian Paddick for the Lib Dems.

Before we took the stage, there was a drinks reception in the rectory. Boris Johnson was holding court, but greeted me to listen to my proposed rules of engagement and graciously remembered that we shared a comment page at the Daily Telegraph at the time. What struck me was that he was softly spoken, genial and engaging.

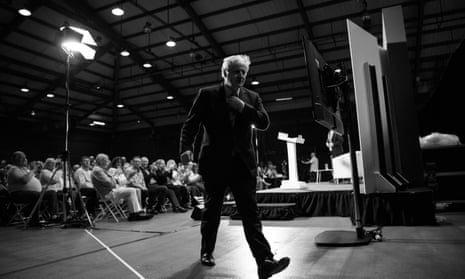

Then, just as we were about to take the stage, he quite deliberately mussed up his hair and adopted his public persona of Blustering Boris, hiding like the Wizard of Oz behind his larger than life caricature.

I had what I hoped was a mildly witty introduction for each of the candidates. But I do remember precisely what I said when I got to Johnson: “Like most Londoners, Johnson went to Eton and Oxford.”

He didn’t take it well. This was lèse-majesté. He scowled up the line and muttered: “Did Livingstone write that for you?” I got the impression he’d barely listened to the others’ intros and was concerned only about his own. He barely treated the debate that followed with any attention at all, looking impatiently at his watch and airily offering generalised banalities in place of answers. And when the evening concluded, he was the only participant to exchange not a word with the other contenders, nor with me as his chairman. This vignette illustrates the Johnson phenomenon in a number of ways. His phoney public image. A hint of narcissism. The magisterial self-entitlement. Cavalier about his electors.

But note also something from that drinks party. It was the first time that Johnson and I had met in the flesh, despite having been fellow columnists on the Telegraph for two or three years. Staff rarely saw him in the office, indeed he was usually referred to as elusive. We both had to file our copy on a Sunday for the Monday edition. I would agree my line with the office after church and send a draft over by late lunchtime. On regular occasions I went to the office to work, to write or to help with the Sunday shift. Funny enough, I never ran into Johnson there; no doubt seeing important people over Sunday lunch was a more pressing concern.

You would expect a busy politician to have to live like that. But a quick telephone call to the comment desk or the subeditors would not only have served as a professional courtesy, it would have aided planning and ultimately saved staff time. It is hard to resist the conclusion that working colleagues simply don’t matter to Johnson.

Johnson was (and is) paid handsomely by the Daily Telegraph for his columns. He was originally commissioned at an unprecedented £250,000 a year by the then acting editor of the Telegraph, John Bryant, but that has risen to £275,000 in recent years. What is truly breathtaking is not just the size of the fee, but it is rumoured that Johnson was originally expected to write two columns a week. Readers never got to see the second one, because in the phrase that’s used by those who will absolve him of anything: “That’s Boris.”

All this could be ascribed to the nature of a public figure having to juggle increasing demands on his time, of which journalistic commitments are just one. But Johnson has indolent form in this regard from his time at the Spectator magazine.

Few of us go into journalism because we’re workaholics. But an editor is a marshaller of talent and a leader and is meant to inspire staff, not dump on them. This is a characteristic of Johnson that some say extended to his London mayoralty. Much of the detailed business at City Hall was conducted by a cadre of deputies, while Johnson pursued photo-opportunities on buses and bikes.

Tim Parker, the serial turnround corporate magnate, was one such deputy who quit just weeks into his appointment. Parker is known for his working maxim that when you make a career error, you should correct it as quickly as possible.

Johnson’s indolence and cavalier attitude matter because, barring a massive public imbroglio for which he would have to withdraw from the contest, he will be prime minister. There is nowhere to hide as PM. Johnson will not be able to rely on his staff to cover for him, as he has in journalism and as mayor.

And how will he cope with his lavish family maintenance commitments when an annual income approaching seven figures is reduced to a meagre prime minister’s stipend of £150,000? At least Johnson will have somewhere to live.

His artifice will be found out in highest office very quickly. When I bump into Tory friends where I live in deepest-blue Sussex and they speak of Johnson’s “charisma” and “character”, I simply observe that they’ve never worked for him. Fairly soon, the whole civil service will be working for him and, unlike the vainglorious groupies who currently prop him up, they will not carry the can for him for long.