I kept walking in on my partner last week quietly crying over the laptop. Not, as might be reasonable to expect, because she is stuck in an infinite current affairs loop, never knowing when she might be freed from the horrors, but because she has been watching Ricky Gervais’s new sitcom, After Life, on Netflix. “You’re not allowed to watch it with me,” she said, pointedly closing the lid. “I’m enjoying it and you’ll ruin it. Go somewhere else.”

Rude, I thought, and then said something about how the reviews hadn’t been very good anyway, which only proved her point. The reviews I read have not been particularly kind, it’s true, but already After Life seems to have reached Bohemian Rhapsody levels of division between what critics have made of it and what real-life viewers think. On a recent episode of Gogglebox, the families who do not usually agree on what they’re watching all collapsed into paroxysms of laughter at a gag about Gervais’s character, Tony, being called a “paedo”.

Though Netflix is notoriously cagey about its viewing figures, anecdotally, it is one of those rare shows that everyone seems to be watching or at least talking about. Outside of newspapers and websites, most people I’ve spoken to have really liked it. It has already been picked up for a second series.

I hate being left out of anything, particularly an argument about whether television is good or not, so I watched After Life alone, where I could only ruin it for myself. I could see the points at which it tries so hard to tug on heartstrings, but it was far more pleasant to allow myself to be emotionally manipulated than to resist and, by the end, I was in bits, having thoroughly enjoyed it and laughed a lot. (One of the few quibbles I had was whether Gervais was eating fishfingers, since I thought he was a vegetarian. That was answered by the internet, which always provides: they are vegan fishfingers.)

One of the issues some people had with the show was that Tony was nasty, but surely he’s supposed to be acting that way. His wife has died and left him in a state of nihilistic despair. His dickishness is the point. It’s well worth reading an in-depth interview that Gervais gave to the New York Times in which he gamely tackles the idea of comedy in an age of social media and cancel culture, and provides plenty of (veggie) food for thought. Anyway, it turns out I would have been safe to watch After Life with. The “paedo” joke is very, very funny.

Jordan Peele isn’t the only one who isn’t a bunny hugger

‘I’m not afraid of them, but I do find them scary,” Jordan Peele told the BBC last week. He was talking about rabbits, which play a part in his new film, Us. “They’re very cuddly but they also have a sociopathic expression and they kind of look past you in a creepy way.” He elaborated on the same theme in an interview with the Guardian. “They’re an animal of duality,” he said. “And they got those scissor-like ears that creep me out.” He also told EW that rabbits are both scary and inane, “so I love subverting and bringing out the scariness in things you wouldn’t necessarily associate with that”.

I am an animal lover. I don’t eat them, I try not to wear them, I put spiders out of the window, gently and I wince when reality show contestants chomp down on a bit of alligator. But I understand that rabbits are inherently creep. Almost everyone I know who had pet rabbits as a child also has some sort of terrible, hushed story of a brutal rabbit-on-rabbit assault, mothers eating their young or demonic pink eyes. There’s a reason that Frank in Donnie Darko isn’t a cat. Don’t get me started on Inland Empire.

Easter attempts to show off rabbits’ cartoonish, cosy, chocolatey side, but cinema is doing us a favour by reminding us of their duality. As they usher in Us, they wave us off from The Favourite, densely multiplying across the frame. In the immortal words of Anya from Buffy, who pioneered bunny terror long before the current vogue for rabbity nightmares: “What’s with all the carrots? What do they need such good eyesight for anyway?”

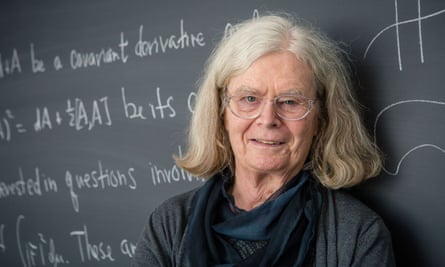

Karen Uhlenbeck – at least it all adds up for her

When prodded to make sense of numbers, they swim and blur before my eyes, then my brain goes on strike, waving tiny placards that say things such as “Algebraaggh!” and “Sum Like It? Not!!” My accountant once replied to what I felt was a normal question with the word “bless”. You know there’s a problem when your basic numerical skills are reduced to a state of “bless”.

It is with wide-eyed and genuine admiration, then, that I read about Karen Uhlenbeck, who has become the first woman to win the Abel prize, sometimes known as the Nobel prize of mathematics. She was honoured for “pioneering achievements in geometric partial differential equations, gauge theory and integrable systems and for the fundamental impact of her work on analysis, geometry and mathematical physics”, which sounds wildly impressive, if difficult to grasp.

It is only one of a long list of honours Uhlenbeck has earned. She joins Emma Haruka Iwao, who recently set a world record for the number of digits of pi that she calculated, in becoming yet another reminder to me that it’s time to get my mathematical basics back in shape.