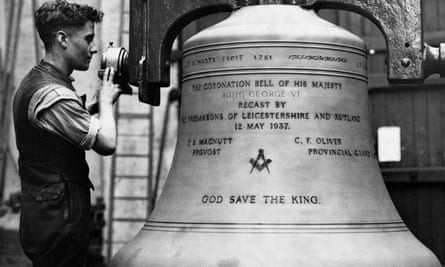

It is said that, every day, 20 million people in Britain hear the chimes of a bell cast at Taylor’s of Loughborough. The foundry is Britain’s last still casting full sets of church bells and has produced them for St Paul’s Cathedral and Yale University among others. You can even hear one tolling on the AC/DC track Hells Bells.

Now, however, the foundry is desperately seeking £4.7m for restorations to its Grade II listed premises just to keep going, the latest challenge to an ancient industry that is struggling to survive.

The Leicestershire site’s supporters are looking anxiously at Whitechapel bell foundry in London, which is facing permanent closure. It ceased operations in 2017 but campaigners hope it will yet be reopened.

Whitechapel, which had operated in the East End since 1570, was Britain’s oldest manufacturing business; it cast Big Ben and America’s Liberty Bell. To the consternation of locals, artists and historians, its new American owners have applied to turn it into a boutique hotel.

“Bells feature in people’s daily lives even when they don’t notice it – just walking along the road and a clock chimes,” said Hannah Wilby, chair of Loughborough Bellfoundry Trust. “If both these foundries disappear it would be a very sad loss for our national heritage.”

Wilby is hopeful that a solution can be found to keep open the foundry, which is operated by Taylor Bells. It has been awarded £300,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund to work up a detailed proposal for a grant of £3.7m, which would be matched by £1m the trust raises itself. “We’re super-optimistic we will raise the money in the end. It’s something we all care so much about. Most of the trustees are bell ringers – I ring at Southwark Cathedral – so we have skin in the game to keep the foundry going,” she said.

Those fighting to see off the developers and reopen the Whitechapel foundry also believe they will succeed, pinning their hopes on a recent groundswell of support from local people that they hope will swing the council’s decision their way. Support has also come from the East London Mosque, which stands very close to the foundry and has significant local influence. The showdown will come when Tower Hamlets council meets on 19 September to consider the planning application.

Among those backing the campaign to reopen the foundry is Dan Cruickshank, the art historian known to millions for his BBC programmes on architectural history. He told the Observer: “There is no better use for an old bell foundry than to be a bell foundry. There is a demand for bells and there is a viable continuation of industrial use on that site. It’s that or another boutique hotel, and the poor East End has lost so much of its authenticity and employment.”

Cruickshank visited the foundry for a programme he was presenting about the Palace of Westminster, and he went to see where Big Ben was cast. “I live nearby, in Spitalfields, and I was used to the story of loss and abandonment and death of spirit in the area,” he said. “But this was an amazing experience – like a dream coming true. I remember thinking, ‘Thank God, there is somewhere still working and doing what it was meant to do.’ So I was heartbroken [when it ceased production], because I had thought it was safe.” He said he was hopeful that the planning process would frustrate the developer’s plans, and the foundry could be saved.

Also behind the campaign are the director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Tristram Hunt, and the metal sculptor Antony Gormley, who used to look into the foundry yard and watch the casting process as he walked through the East End.

The UK Historic Building Preservation Trust also hopes planning permission for the developer’s scheme will be refused, and its offer to buy the foundry and start casting bells there again will now succeed.

Stephen Clarke, a trustee, said: “This is Britain’s oldest continuous business – it’s part of the locality’s DNA – and we want to put in new technology so we can continue and regenerate that business. We have a lot of potential commissions we can put through that foundry, many of them coming from overseas and China in particular. “Whitechapel bells are a global brand and they should be kept as a global brand. You walk in and you smell the dust and you are surrounded by the most fantastic atmosphere. Yes, it’s been shut for two years now, but my goodness me! That building is crying out to be opened up and the furnaces turned back on.”

Back in Loughborough, Wilby agrees there is great potential from the export business. She returned last week from Singapore, where the cathedral had just hung Loughborough bells. And, even if the lottery grant doesn’t come through, she pledged they would fight on: “We’ll keep going. As long as that building is repairable, we’ll absolutely keep going.”