Fattened up with acorns and chestnuts to the size of a cricket ball and then stuffed, baked and perhaps seasoned with honey and poppy seeds, the dormouse was one of ancient Rome’s most popular delicacies.

The Romans also adored dishes such as rabbit stuffed with figs, cockerel in pomegranate sauce, and terrines and mousses moulded in to the shape of chickens.

A wealthy family reclining, not sitting, to eat their meal might start with snail, egg or fish appetisers before a goat or pig main course and then finish with a dessert, mainly fruit such as apples, plums, grapes, cherries, dates and figs. All liberally seasoned with fish sauce. And accompanied by gargantuan quantities of wine.

The Roman love affair with food and drink is explored in a major exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, opening on Thursday. Titled Last Supper in Pompeii, the show includes about 300 objects loaned by Naples and Pompeii, many of which have never left Italy before.

For Paul Roberts, the exhibition’s curator, staging the exhibition is the fulfilment of a dream he has had since 1976, when he first visited Pompeii with his mum. “I was bowled over by the real life because I’d thought of Romans as gladiators, emperors and people who were in my Latin books and then suddenly in Pompeii, there were real people.”

What better way, said Roberts, for us to connect with the ancient Romans as ordinary people than through food and drink?

The exhibition includes actual food carbonised by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79. It shows what the inhabitants of Pompeii ate and drank, why enjoying it was so important, and how they made their meals.

For example, the short but sweet life of the dormouse is highlighted by the display of a large terracotta jar, a glirarium, in which dormice were deposited and encouraged to get fat as if for hibernation. They were fed acorns and chestnuts through holes in the side.

Roberts has placed a stuffed toy dormouse at the top of the jar to show how fat they got and that they were not as tiny and spindly as modern visitors might imagine. Nearby are kitchen utensils that would have been used to cook them.

They were evidently delicious, and consumed in vast numbers. “I’ve not had one myself,” said Roberts. “But friends have and apparently they taste like a cross between rabbit and chicken.”

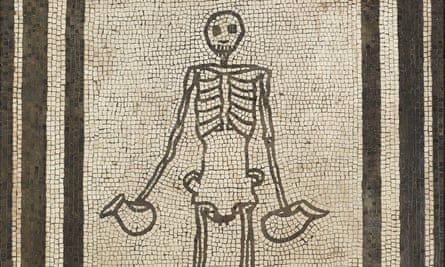

The show includes star objects from collections in Italy, including a startling mosaic of a grinning skeleton that decorated a dining room floor in the House of the Vestals. It is literally death at the feast.

Roberts said it was a masterpiece. “It reminds you while you’re dining that this is the epitome of life, friends, family, business acquaintances.”

Fortunately the skeleton is carrying wine jugs in each hand, indicating that there will at least be wine in the afterlife. It’s main message though is, Roberts said, “that you’ve got to seize the day … carpe diem.”